Book Review and Commentary: Testaments to the Wonderful Ears of Ralph J. Gleason

A writer usually has to make a choice: to write for the now or to write for the ages. Ralph J. Gleason almost always chose the now, but his best moments go deeper.

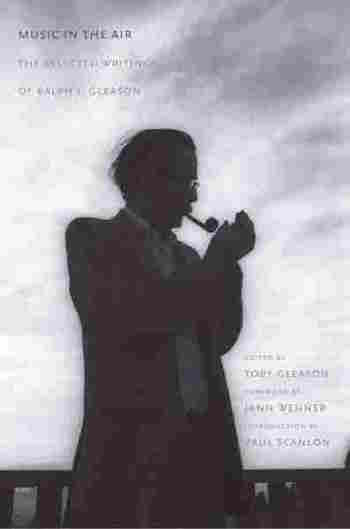

Music in the Air: The Selected Writings of Ralph J. Gleason. Edited by Toby Gleason; Foreword by Jann Wenner; Introduction by Paul Scanlon (Yale University Press, 328 pages, $30)

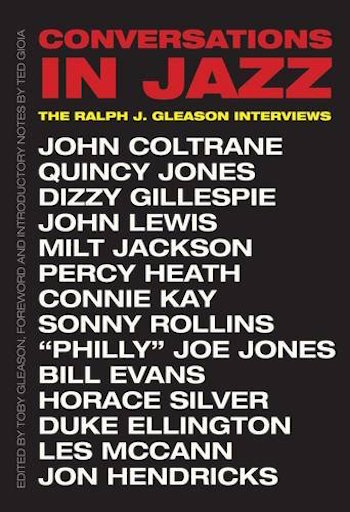

Conversations in Jazz: The Ralph J. Gleason Interviews Edited by Toby Gleason; Foreword and Introductory Notes by Ted Gioia. (Yale University Press, 296 pages, $30)

By Steve Elman

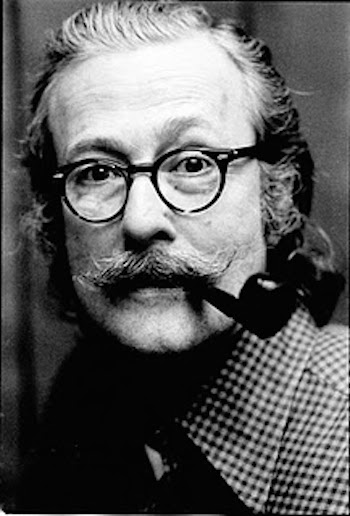

Ralph J. Gleason. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Ralph J. Gleason was an enthusiast. He was many other things, too – columnist, essayist, journalist, editor (sort of), impresario (sort of), gadfly, friend of all jazzpeople, and enemy of Richard Nixon. But enthusiast is how I remember him, and enthusiasm is what first attracted me to his writing. Unlike his chronological peers in what might be called the first generation of American jazz writers – Stanley Dance, Leonard Feather, Martin Williams – he never wrote scholarly criticism, and he preferred a breezy, vernacular style. Unlike younger critics with whom he is often grouped – Whitney Balliett, Ira Gitler, Nat Hentoff, Dan Morgenstern, A. B. Spellman, and others in the “second generation” – he was not a writer who limited himself to jazz, or to art music in general.

It probably is inaccurate to call him a critic at all. He was a man of his time (1917 – 1975), reacting to the music and events of his time. His liner notes (remember liner notes?) for Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew, a heady stream-of-consciousness spritz presented entirely in lower-case type, seemed entirely appropriate to me when I first picked up the LP set in 1970; he obviously sensed that the recording was a watershed and that it deserved a new kind of prose accompaniment.

Gleason couldn’t confine himself to writing. He hosted programs with live jazz performances on public TV, and those “Jazz Casual” shows (1960 – 1968) remain important documents of a vital time. He helped found the Monterey Jazz Festival and tirelessly promoted it. When it became clear that rock and roll needed a weekly magazine, he and Jann Wenner started Rolling Stone, and his name still appears on its masthead.

A heart attack killed him at 58, in 1975. In the last decade of his life, he had witnessed the deaths of jazz gods he loved: Louis Armstrong, Ben Webster, John Coltrane, and Duke Ellington. But Miles Davis was still alive. So were Bing Crosby, Charles Mingus, John Lennon, Count Basie, Thelonious Monk, and Elvis Presley. Bruce Springsteen was just beginning his ascendance when Gleason passed away. He did not live to hear Prince, or minimalism, or Steely Dan’s Aja, or Wynton Marsalis.

He reveled in Nixon’s resignation; he would have been dumbfounded at the election of Ronald Reagan. He bitterly opposed the Vietnam War; his stomach would have turned at Pol Pot’s Cambodian genocide. He saw many jazz musicians embrace Islam as an alternative to Christian religions that had supported slavery in America; he would not have understood the phrase “radical Islamic terrorism.”

Reading him in his time was bracing and edgy. When he was right, you felt that he was absolutely right. When he was wrong … well, at least his heart was right there on his sleeve where you could see it. Reading him now, in two new collections of his work from Yale University Press edited by his son Toby, is surprising. Like Peter Pan, his writing remains forever young, intrepid, brash. But, if I may turn Bob Dylan’s familiar paradox back onto its feet, we were so much younger then; we’re older than that now. Gleason’s work hasn’t changed, but he did not live to see what we have seen. He suddenly seems imprisoned by time, and in quite a few ways, these two books are cautionary tales for enthusiasts everywhere, myself included.

The writing, from a tiny “Perspectives” column in Down Beat in September 1954 to a mammoth appreciation of Lenny Bruce accompanying the release of a Bruce anthology in 1975, is fired by contemporaneous emotions, untempered by the illusions and disillusionments to come. There is indignation over the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam debacle, intoxication with the San Francisco scene in 1967, scorn for the sleazy Sinatra of 1974 who had stolen the soul of the Frank so admired in the late 1940s. He is at first “deaf” to Bob Dylan, and then suddenly understands; he brings us along as his enthusiasm grows.

It is honest and charming writing, but it is not prophetic. As Jann Wenner writes in the foreword to Music in the Air, his popular music and cultural pieces in the pages of Rolling Stone were the words of an éminence grise, an old guy — like, 50, man — writing about what was happening without any complaints about the kids on his lawn.

A similar kind of haze surrounds the jazz pieces. In Conversations in Jazz, Gleason interviews giants – Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, Bill Evans, all the members of the Modern Jazz Quartet, Horace Silver, even Duke Ellington – as casually as if they were next-door neighbors. But all these interviews come from 1959, 1960, and 1961, as golden a time as any jazz fan has ever experienced, when Coltrane recorded “Giant Steps” and his first live sessions at the Village Vanguard, when Miles and Gil Evans recorded “Sketches of Spain,” when Max Roach created his “Freedom Now Suite,” when Oliver Nelson recorded “Blues and the Abstract Truth,” when Bill Evans and Eric Dolphy both led career-defining live sessions at the Five Spot in New York, when Stan Getz recorded Eddie Sauter’s “Focus” and the MJQ premiered the first third stream pieces by Gunther Schuller. The interviewer and his subjects understand their subordinate place in the big sweep of American life, but they envision better times ahead. They never guess that each subsequent decade would find jazz less prominent in the American mind than it had been in the decade before.

Fortunately, these conversations have a measure of lasting value, for two particular reasons. First, there are some unguarded moments of revelation, as when pianist John Lewis and bassist Percy Heath in separate interviews both acknowledge that Heath had to do a lot of work to come up to the musical standards Lewis expected of players in the MJQ, or when Quincy Jones talks about the problems of managing a big band: “This is the one thing [Count] Basie has trouble with. The guys [in his band] get pretty bored.”

Second, Gleason’s probing questions go to the core of the jazz experience as few other interviewers do: “Are you ever satisfied with anything you’ve done?” “Have you continued to work out problems on [your] instrument?” “What challenges are you setting [for] yourself?” “[When you play in a jazz club], do you try to work out the acoustics of the room?” And he shows that he appreciates the ephemeral nature of jazz perfection, grilling Coltrane and Gillespie to describe what they feel like when “everything is right.”

A writer usually has to make a choice: to write for the now or to write for the ages. Gleason almost always chose the now, but his best moments go deeper. He can be deeply moving, as he is remembering Billie Holiday for a 1962 LP reissue of her work: “I remember when she opened at Café Society in December, 1938 … standing there with a spotlight on her great, sad, beautiful face, a white gardenia in her hair … she never knew how many people loved her.” He can be profound, as he is discussing Dick Gregory’s work in 1963: “In a culture of evasion and euphemism … telling the truth cannot help but shock.” And he can be prescient, as he was during the Nixon – McGovern election campaign of 1972: “I know you are tired of politics. Can you know how tired I am? I cast my first vote for [Franklin] Roosevelt when we lived in an era when a man in public office could be trusted … Maybe there is no hope. Yet I can’t accept that because if I did then there would really be no choice but death and I opt for life and love every time.”

There are a few pieces Toby Gleason chose for Music in the Air that don’t add anything to his father’s reputation or to the legacy of the musicians he discusses – a 1962 review of a children’s album by The Limeliters; a 1963 survey of high school and college jazz bands in northern California; a column on Bola Sete and Vince Guaraldi from 1964; another column from the same year that takes seriously the rumor that John Lennon and Bob Dylan may be the same person; and liner notes for Cal Tjader’s less-than-memorable Los Ritmos Calientes (1973).

There are sentences, dramatic when written, which time has eviscerated: “[The Beatles] sing with a wild, roaring sound.” “Nobody has ever made it in their own terms as a white girl singing black music the way Janis [Joplin] did.” “The [Rolling] Stones’ music is great music, but it almost always hangs there on a thin edge of violence.”

Gleason recognized an authoritative performance by saxophonist Ben Webster. Photo: Vebidoo.com

He has his blind spots. Helen Merrill is called “a singer of doubtful quality.” Laura Nyro is “an affected and pretentious performer.” Though he admires the music of Dizzy Gillespie’s big band and praises the innovative spirit of Miles Davis, he does not mention George Russell, who contributed mightily to the thinking of both; the only mention of Russell comes from Bill Evans, in an interview answer, and there is no follow-up. Gleason also fails to see the essential beauty of the classics of the American songbook, which he disparages as “the standard Broadway show / Ed Sullivan TV program popular song.” Example: “[Louis Armstrong’s] great thing was to take the lyrics of some silly song, ‘Stardust’ is a good example [sic], and treat those insipid lyrics in such a fashion that they become a work of put-on art.” Sorry, Ralph. “Stardust” is a Hoagy Carmichael masterpiece, and if Mitchell Parish’s lyrics aren’t quite up to the standard of Carmichael’s music, they have elegance and grace, and the genius of Armstrong’s version is not that he burlesques the words, but that he has fun with them at the same time he shows respect for the feeling behind them.

And how is it that such a perceptive writer could occasionally sound so naïve? “If we were a truly moral people, there would be no professional boxing.” (1974) “When you are good and have something to say, if you have the conviction of your own worth and of the rightness of your message, you eventually will find a way to play what you want and get paid for it. And if, after years and years, you do not, it just might be possible that what you have to say isn’t worth hearing.” (1954)

I came away from reading Music in the Air with my own enthusiasm for Gleason muted a bit. However, in one way it reinforced my old impressions of his work. His liner notes for a Jimmy Witherspoon LP, At the Monterey Jazz Festival (1959), were so vivid that they sent me off to Spotify to see if I could hear the recording online. Sure enough, there it was, and Gleason’s observations turned out to be right on the money. This was much better music than I knew from any of Witherspoon’s other recordings, especially because of the all-star supporting cast – Earl Hines, Roy Eldridge, Woody Herman, Coleman Hawkins, and Ben Webster. As I read on, the music faded into the background, until I was brought up short by a tenor saxophone solo so authoritative that I had to see what Gleason said about it. He heard that special quality just as I had, except that he was present at the performance itself and not just a writer hearing a recording of it. He pointed to “[Ben] Webster’s magnificent solo,” and added, “Backstage later, Witherspoon summed up the entire audience reaction … ‘Ben wrote his name tonight,’ he said.” That solo stuck with Gleason, so much so that he mentioned it again in his Rolling Stone remembrance when Webster died fourteen years later. Toby Gleason had the good sense to put both of these pieces into the collection, and they are perfect testaments to his father’s wonderful ears.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.