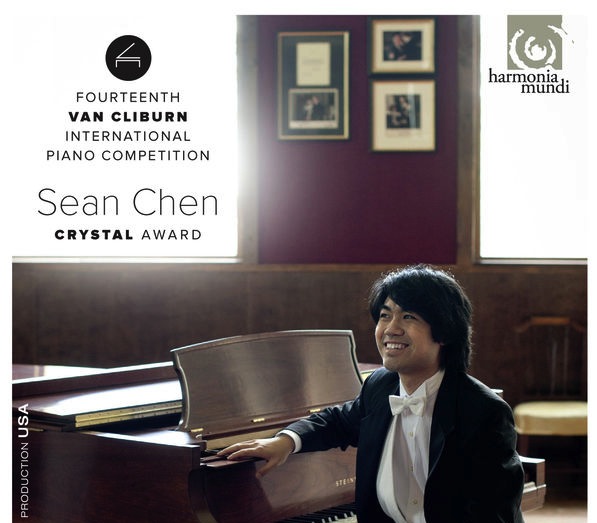

Classical CD Reviews: Van Cliburn Competition Finalists – Vadym Kholodenko, Beatrice Rana, and Sean Chen (Harmonia Mundi)

There are fistfuls of notes and some tremendous technical skill. But, with a couple of notable exceptions, the readings of some of the cornerstones of the solo piano repertoire by each pianist are most notable for their lack of direction and interpretive facelessness.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The Van Cliburn Competition has had a rough several years. Criticized for the dearth of world-class pianists it has produced (Radu Lupu remains its most famous Gold Medalist; he won in 1966) and the choices of its judging panels scrutinized time and again, this past February it lost its namesake to bone cancer. At a time when some good news would have been especially welcome from Fort Worth, Harmonia Mundi’s new set of albums by this year’s Competition’s three finalists – Gold Medalist Vadym Kholodenko, Silver Medalist Beatrice Rana, and Crystal Award winner Sean Chen – mostly reinforces the general sense of pessimism about this once-prestigious event. Yes, there are fistfuls of notes and some tremendous technical skill, to be sure. But, with a couple of notable exceptions, the readings of some of the cornerstones of the solo piano repertoire by each pianist are most notable for their lack of direction and interpretive facelessness.

*****

Gold Medal-winner Kholodenko has brilliant technique to spare and he best demonstrates it in Stravinsky’s Trois Mouvements de Pétrouchka. Arranged for Arthur Rubinstein by the composer from the eponymous ballet in 1921, it’s a three-movement piece that summarizes the earlier score’s main elements, beginning with the scene in which Pétrouchka comes to life and closing with the fair; in between is a movement depicting Pétrouchka’s loneliness.

It’s a wild and often showy piece, and Kholodenko responds to it in kind. It’s hard not to be impressed with his Technicolor performance, especially in the outer movements, which are boldly drawn and vividly characterized.

If only the same could be said of Kholodenko’s account of Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes. Unfortunately, in this performance one comes away most impressed by the sheer audacity of the pianist performing all twelve of these fearsomely demanding movements in one sitting. Actually he didn’t play all twelve at once, since, strangely, no. 9, “Ricordanza,” dates from a 2008 studio session in Moscow. But no matter: surely the list of pianists who program this piece mostly complete is still a relatively short one.

As relentless as these movements must be to play, they also can be tough to listen to in succession, especially if the pianist doesn’t offer enough variety. In his performance, Kholodenko provides some striking moments: “Feux follets” is marvelously light and fresh, and sparks fly in “Mazeppa.” But for much of the remaining ten movements, there’s a certain rigidity of tone and stiffness to the playing.

Too often the performance feels like a marathon. I’ve never heard a brisker reading of “Paysage” (this one doesn’t nearly crack the four-minute mark; the average duration usually runs around five), nor do I want to. The result here is akin to dashing through an art gallery while taking quick glimpses at all the landscapes: everything is a blur and the experience leaves a negligible impression. It’s hard to imagine a less epic “Eroica” than Kholodenko’s, though that has less to do with speed than a general lack of articulation and character. And so forth. Lazar Berman took these movements quickly, too, but he brought a depth of understanding to this music that Kholodenko simply doesn’t possess. Or, if he does, he’s hiding it.

It all adds up to a frustrating, indistinct run-through of what can be a thrilling piece: one comes away most impressed by Kholodenko’s stamina and technique, but his interpretive chops run far behind and this performance imparts no significant musical insights.

*****

Similar troubles dog Silver Medalist Rana’s interpretation of Robert Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes. Again, there are moments that really impress. Rana has a firm grasp of Schumann’s poetic voice and delivers a performance that’s rich in tone and never feels hurried. Her rhythmic precision in Etudes nos. 9 and 10, especially, is breathtaking.

But, on the whole, these Etudes never quite escape sounding like, well, formidably difficult exercises: the sforzandi in Etude no. 4 lose their punch as the movement progresses to become a kind of ball of loud muddle; the refrain of the heroic finale consistently sounds untidy; and, throughout, there’s the sense that a greater adherence to the Etudes’ dynamic range would have allowed the music to speak more clearly, especially in its middle movements.

More successful is Rana’s performance of Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit. Her textures are gossamer and she fully inhabits the music’s macabre, ghoulish character. Particularly striking are the middle movement, with its ominously tolling B-flat octaves, and the finale, depicting a goblin scurrying and dancing in the shadows, the reading here captures much of the music’s turbulence and dark humor.

Best of all, though, is Rana’s take on Bartók’s Out of Doors, a suite of movements based (mostly) on eastern European folk music. She delivers the wild, punching rhythms in the opening movement (“With Drums and Pipes”) with as much attention to detail as she does the haunting opening of the fourth movement (“The Night’s Music”). As in the Ravel, she also draws out much of this music’s color: one gets the sense that she has a special affinity for Bartók’s distinct voice.

*****

Music by Bartók also figures on Sean Chen’s Crystal Award-winning performance. His selection is Bartók’s less-familiar Three Etudes, op. 18, a wild, rhapsodic tour-de-force of a piece that marries the gestures of the great Romantic keyboard literature with a tangy, Modernist vocabulary. Chen plays it all very well, easily conjuring up the music’s spirit and zany energy.

Equally good is his account of Brahms’s Variations on an Original Theme, op. 21. There’s really nothing to criticize here: it’s a beautiful performance, shapely, elegant, and richly tonal. This is a piece that features a lot of slow music, but the energy of Chen’s performance never flags and the quick, later variations really crackle.

The heart of this disc is devoted to Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” Sonata (op. 106) and, as with Liszt and Schumann on the earlier albums, here things falter a bit. As before, there are strong moments: the opening movement features lots of forward momentum, the Scherzo is light and crisp, and the fugue in the finale sounds steely as ever. But, on the whole, the wild contrasts of mood, texture, and style that are one of the prime hallmarks of late Beethoven are only shallowly explored – they come off too nicely. And the dramatic intensity that lies underneath the surface of much of this music isn’t ever fully tapped. Still, Chen fares best among the three finalists: he clearly has some very strong ideas about each of the pieces he plays and he turns in the most satisfying disc of the trio.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Beatrice Rana, Harmonia Mundi, Sean Chen, The Van Cliburn Competition