Book Review: “Learning to Listen” — Vibraphonist Gary Burton’s Musical Journey

“Learning to Listen” is less about a jazz journey than it is about a prodigiously talented artist for whom music came easily while his own life was a puzzle.

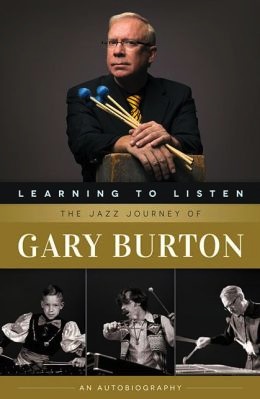

Learning to Listen: The Jazz Journey of Gary Burton, by Gary Burton. Berklee Press, 400 pages, $27.99

By Jason M. Rubin

When great artists write their memoirs, one typically hopes to learn something of what lay behind their creative accomplishments; the secrets to their success, as it were. One also, it must be admitted, hopes to get a little behind-the-scenes dirt as to love affairs, observations of famous people behaving badly – the kind of backstage secrets we as listeners and fans are not privy to (unless the artist in question is Taylor Swift or Miley Cyrus).

With Learning to Listen, the recent autobiography by the brilliant jazz vibraphonist Gary Burton, we get too little of the former and too much of the latter. Along the way, we get interesting nuggets about his life and career and experiences with various collaborators, but too often they are superficial views of select moments in a long musical career. The reader is left wanting more details about specific album projects, particular compositions, and how Burton developed his unique four-mallet technique. Sadly, we are left without enough substantial information – or, to be more fair, we are left with tidbits when what we are hungry for is a larger feast.

We do, however, get lots of dirt on famous musicians, much more than is necessary, frankly. In particular, Stan Getz, Bill Evans, and Joe Henderson are targeted for a great deal of mudslinging. Surely, some of it is earned because of their own bad behavior and can likely can be corroborated in other accounts, but when a brilliant artist like Bill Evans is discussed 80% of the time in terms of his drug use and only 20% of the time in terms of his music that is not right or informative. Furthermore, while there are more than enough firsthand accounts of abusive behavior and drug addiction, Burton piles on the gossip by tossing in secondhand accounts from people he doesn’t even name (e.g., “a bassist friend” or Miles Davis’ tour manager). This is both bad taste and bad journalism.

One of the key elements of Gary Burton’s life story, and therefore of the book, is his long struggle to accept his orientation as a homosexual (he was twice married to women, and has two children and one grandchild). In the book he comments on his sexuality in the context of scenarios in his life that occurred well before he figured out his desires. It is valuable for Burton to reflect on this issue because it is an important part of his voyage of self-discovery, but often the subject turns up as an unwelcome tangent to the narrative.

Still, it’s hard for this writer to comment on Burton’s approach too harshly because he pushed the question aside for so much of his own life. Why should Burton segregate the subject of his homosexuality to one chapter? And, indeed, he does delve into it more deeply towards the end of the book, in a chapter called “Who Is Gary Burton?” But again, he seems to emphasize the subject of homosexuality at the smallest opportunity throughout the volume, such as when he questions whether Duke Ellington was gay or confirms that Samuel Barber was.

In addition, there are a number of instances where Burton’s prose generates grimaces. One example is when he describes an early experiment fusing jazz with country music. Of the unsuccessful effort, he writes, “This wasn’t the only occasion in which I was ahead of my time.” Another is when he writes of performing for a Mafia function and calls his sponsors “honorable businessmen.”

Aside from these criticisms, Burton’s book is very informative in parts. Though the storyline progresses through the events in his life more breezily than most readers would have liked, Burton includes numerous sidebars in which he focuses on particular subjects with impressive historical detail and personal observations. These ‘deep dives’ include the differences among different mallet instruments and profiles of key musicians with whom he has worked, including George Shearing, Stan Getz, Chick Corea (who gets, by far, the most glowing accolades in the book), Lionel Hampton, Samuel Barber, Pat Metheny, and Astor Piazzolla. More often than not, these portraits are quite illuminating and even rather touching.

Boston-area readers will be interested in Burton’s long association with Berklee College of Music. When he first became a student there in the fall of 1960, Berklee consisted of a single brownstone building on Newbury Street and had a student population of approximately 100 budding musicians (today, Berklee has 4,000 students). Burton’s first apartment down the block from the school cost him all of nine dollars a week in rent. Over the years, he returned as an instructor, Dean of Curriculum, and eventually Executive Vice President, where he introduced rock instruction, online courses, and a music therapy program that is currently the largest of its kind in the country.

Only at the end of the book, in the chapter “Understanding the Creative Process,” does Burton begin to reveal some of the secrets of his improvisation techniques. (This is interesting stuff, though if you want more detail you have to register for his online course on the subject.) His thoughts on performing – and communicating through his performance – for non-musicians are also compelling. Given the complexity and sophistication of his music, he understands that non-musicians listen to and appreciate music in a different way than do his peers. This is one of the few times in the book he is nonjudgmental, in comfortable teaching mode, and it is refreshing.

Ultimately, Learning to Listen is less about a jazz journey than it is about a prodigiously talented artist for whom music came easily while his own life was a puzzle. It is, then, a journey towards self-knowledge, not as a musician or even as a homosexual, but as a man. As Burton writes, “Twenty-five years ago I told Terry Gross [on NPR] I was a jazz musician who happened to be gay. Later, I came to think of myself as a gay guy who happens to be a jazz musician. Perhaps it’s more accurate to say I’m just a guy who happens to be gay and happens to be a jazz musician.”

In his memoir, Gary Burton comes off as perhaps too gossipy a man, too willing to settle old scores. But having found success and peace, in his career and his life, he has many compelling things to say. If you like his music, you will most likely gain a deeper appreciation for it once you have a deeper understanding of its source.

Jason M. Rubin has been a professional writer since 1985. He is an award-winning copywriter and a novelist whose first book, The Grave & The Gay, based on a 17th-century English folk ballad, was published in September 2012. He lives in the Boston area and also writes CD reviews for Progression magazine.