Book Review: In Pitigrilli’s Intoxicating “Cocaine,” Love is the Drug

Cocaine’s bleak and brilliant satire, lush and intoxicating prose, and sadistic playfulness remain as fresh and caustic as they were nine decades ago.

Cocaine by Pitigrilli. Translated by Eric Mosbacher. New Vessel Press, 258 pages, $16.49.

By Peter Keough

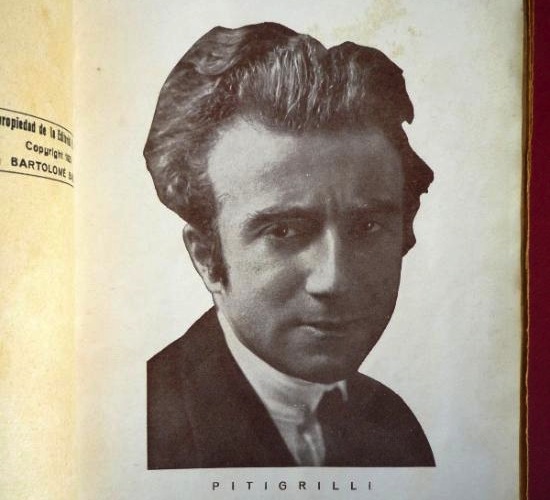

The 1920s saw the triumph of the great modernists: Joyce, Proust, Eliot, Hemingway, and … Pitigrilli, a.k.a. Dino Segre.

In 1921, the year that Luigi Pirandello first staged Six Characters in Search of an Author, when the publishers of The Little Review were convicted of obscenity by the New York District Court for publishing the “Nausicaa” chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses, and Proust had published Cities of the Plain and The Guermantes Way, the 28-year-old Italian’s novel Cocaine scandalized and delighted readers across Europe. Like many other modernist texts, Cocaine defied traditional literary conventions, employing techniques of self-reflexivity, stream of consciousness, and allusions to masterpieces of Western and other civilizations to relate the adventures of a picaresque anti-hero lost in the vacuum of a world morally devastated by World War I. Like the drug of the title, the novel stimulated unwholesome exhilaration, deranged epiphanies, and seductive despair.

Okay, so it wasn’t as revolutionary as some other works in the modernist canon, and has since sunk into obscurity (this New Vessel Press edition, translated by Eric Mosbacher, is the first in English since 1982). But in its day it was a big deal. It was translated into 18 languages. The Church added it to its “forbidden books list.” One of its fans, Benito Mussolini, himself the author of a popular anti-clerical novel and about to march on Rome and take over Italy, defended the book and its author against detractors. “Pitigrilli is not an immoral writer,” Il Duce opined. “He photographs the times.” Later, in the 30s, Pitigrilli would work with the fascist secret police OVRA (Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism). These credentials would both help and hurt him as the “cunning passages and contrived corridors” of history, as T.S. Eliot puts it in his 1920 poem “Gerontion,” eventually proved to be a trap.

More on that later. In 1921, though, such looming catastrophes didn’t mean much to those enjoying the ongoing carnival of nihilism, hedonism, and ennui. Cocaine dabbles in those themes with sardonic wit and with the abiding, gleeful sadness of debauched romanticism. It recalls authors as diverse as Nathanael West and the Marquis de Sade in its chronicle of 20-year-old Tito Arnaudi, a cynical, charming, precociously world-weary anti-Candide introduced in a paragraph that sounds like a flippant take-off of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

At the college of the Baranabites he learned Latin, how to serve mass and how to bear false witness —skills that might come in handy at any time. But as soon as he left he forgot all three.

So much for religion. Tito next moves on to medicine. After three years of medical school, he refuses to take a pathology exam because he is not allowed to wear a monocle. So he drops out. He settles into being a dandy along Wildean lines, filling his idle hours mulling over aphorisms such as “Women are like posters. One is stuck on top of another and covers it completely.” Or, “Life is an arc from A to B.” Or, “Love … is always exactly the same.” And so on.

As might be expected, this callow cynicism in fact conceals a romantic soul, and one of his bon mots (“We all twirl the hairs we have, depending on our age and sex”) wins the heart of Maddalena, “a decent girl, though she went to secretarial school.” He, in turn, falls in love with her.

As Pitigrilli explains, “That is something that happens to young persons of both sexes when they are no longer nineteen and are not yet twenty-one. Afterwards we look back on it with regret as a fabulous age we did not sufficiently treasure.” But Maddalena’s bourgeois, rigidly Catholic parents disapprove, and shuffle her off to a reformatory. Tito, bitter and heartbroken, seeks solace in the decadent demimonde of Paris.

And what profession is more decadent than journalism? An uncle in America (“You mean to tell me that uncles in America really exist?” an incredulous acquaintance asks), a newspaper editor, offers Tito a job as a reporter, assigning him to write a story about cocaine addicts. For research, Tito visits a local cocaine den, and his description of the addicted female habitués resembles Reefer Madness by way of Ken Russell’s The Devils:

[T]he four harpies didn’t calm down. Panting, with dilated nostrils and flashing eyes, they clawed at the box of white powder, like shipwrecked persons struggling for a place in the lifeboat. Those four bodies round a little metal box, all in the grip of the same addiction, looked like four independent parts of a single monster greedily writhing round a small, mysterious prize, elevating its cheap pharmaceutical crudity to the dignity of a symbol. All Tito could see was half-clenched hands that looked numbed with pain, hands with pale, bony, hooked fingers that turned into tightly clenched fists with nails sticking into palms to suffocate a shriek, or quell a craving, or give pain a different form, or localize it elsewhere.

What a turn-on. Fortunately, the writing gets a little less hysterical as the story goes on. Naturally, and also in the interests of research, Tito tries some coke himself. He, too, becomes addicted, but not to the drug. As is evident from his description of the four female addicts, and from repeated misogynistic asides and comments made by him and others throughout the text, Tito does not think much of women. Or rather, he thinks about them all the time – two in particular, one of whom he finally refers to as “Cocaine.” In short, like the harpies above, he has elevated what he considers cheap crudities – women (dismissed by one of his cronies as “roving uteri”) – to the dignity of symbols – symbols of unfulfillable desire.

But the women Tito obsesses over exist in a more rarefied realm than the hell holes of the coke fiends he disdains. The success of his article earns him a sinecure on a popular newspaper, aptly named The Fleeting Moment, giving him entree to fashionable pleasure domes such as the villa of Madame Kalantan Ter-Gregorianz, where the rich and famous and the parasites thereof indulge in orgies that recall scenes from Fellini’s Satyricon and Dante’s Inferno. There, the insouciant Tito watches, snorts cocaine, and swaps barbed badinage with the other voyeuristic revelers. They include painters, scientists, physicians, and other journalists – sycophants and vanity cases with names like Triple Sec, Professor Cassiopeia, Dr. Pancreas, and Professor Où Fleurit l’Oranger.

Diverted by their own snide put-downs and backstabbing, these decadents ignore the “completely nude and depilated woman” engaged in a “Bengal dance,” lament the deaths of the hundreds of exotic Brazilian butterflies released by their hostess for their amusement, and sample such toxic treats as strawberries soaked in ether, straight chloroform, or good old-fashioned morphine. The night ends in a kind of primal soup of spent or impotent lust, inebriated oblivion, puddled booze, and dead brain cells:

Everything in the room had become phantasmagoric: human voices gave forth non-human sounds; the light coming from numerous sources and reflected again and again had the wavering liquid transparency of an aquarium; straight lines bent; a vague, flowing motion replaced solidity and seemed to breathe life into lifeless objects; and all the people, with their slow, flaccid movements, who drooped, fell and writhed on the floor among the multi-colored cushions with disheveled hair, half naked and surrounded by broken glasses, were like creatures in an aquarium whose liquid environment softened and slowed down every movement.

“The greenish carpet, splashed with spilled liquor, was like a muddy ocean floor on which the cushions were shells and the women’s loosened hair the fibrous tufts of byssus or the fabulous vegetation of submarine landscapes.”

Next stop, Pasolini’s Salò.

In this infernal (or perhaps paradisal) setting, Tito at last beholds his Beatrice, or at least the woman who will play that role for the time being, when he is smitten by a vision of the hostess, Kalantan. Or not so much by the hostess herself, per se, but by the little cup formed by the back of her knee as she lies passed out and face down on the floor. He pours champagne into the fleshy receptacle, drinks it, murmurs her name, and passes out himself.

Two things, or perhaps three, prevent Tito from finding in Kalantan the ideal beloved whom he will never attain but whose elusiveness will serve as a guiding star for all his subsequent delusions.

First of all, Kalantan herself, who until she met Tito had been a belle dame sans merci, a fearsome dominatrix who made love in a coffin and took on and discarded lovers like a man does. But now she has become even more obsessed with Tito than he is with her. Renouncing her endless quest for the ultimate in refined and forbidden sensation, she has dedicated herself solely to him, offering herself up as his paramour, patroness, and acolyte.

Secondly, his relatively innocent first love, Maddalena, has returned from the reformatory transformed into “Maud,” now a dancer “in tails and a top hat” of mediocre talent but far different from the “rather ugly, rather stupid girl whom he had met on a balcony two years before.” She has become a vivacious, lascivious ingénue who “wore kangaroo gloves and used difficult words like idiosyncrasy, eurhythmics and quadrilateral and spoke them with pedantic accuracy.” These qualities entice him, but it is her unapologetic and incorrigible promiscuity that wins him over. As Pitigrilli explains:

He had begun to fall in love with her at the moment when … she told him how she had given herself to a man for the first time […]

That was sufficient to arouse in him a disturbing jealousy of the past, the pain of not having been the first and only man in her life, a hatred of all the men who had had her and a hatred of her for having given herself, a hatred of the time that had brought this reality into being, a hatred of the reality that could not be changed, and an even greater hatred of the time to which he could not return.

So Tito finds himself in a diabolical dilemma. Kalantan may be his, but she torments him because of her past of endless lovers and debauchery when she belonged to somebody else (primarily herself, as a matter of fact). Maud, no longer his, now has become like the Kalantan of old, an inexhaustible seeker of new pleasures and new lovers who torments him because of her infidelities – past, present, and to come.

As he helplessly recognizes,

Between these two women, these two passions. Tito was undecided. He couldn’t make up his mind by which to let himself be carried away. He was intra due fuochi distanti e moventi, between two distant and powerful fires …

Oh, that Dante Alighieri, he has managed to get himself quoted even by me.

To resort to a more contemporary comparison, Tito has succumbed to the same fate as the two morbidly jealous cuckolds in Proust’s “Swann in Love” and The Captive. Like them, he does not suffer simply from insatiable jealousy. The real punishment is lost time itself, the impossibility of capturing any moment, and especially the moments experienced by others. Failing that, all that remains is solitude and loss.

Unless … and this brings up the third obstacle to Tito finding satisfaction in love, or at least by way of the morbid delectation of obsessively pursuing someone who will never return or satisfy his passion. Whether he acknowledges it or not, he has already moved beyond such amatory wild goose chases, and found a substitute in his casually adopted profession, journalism, or to be more accurate – as his reporting becomes more and more the product of his imagination – the act of writing itself.

Here’s how that happens: Having distinguished himself with his cocaine story, Tito gets another assignment – covering the death by guillotine of a convicted serial killer. However, the execution takes place the day after the orgy at the villa of his new soul mate Kalantan. Besotted and hung over, he decides that he doesn’t really need to attend the execution in order to write about it. He can make it up from his room, padding a purplish account with the kinds of recalled or invented factoids that someone in a similar position these days would obtain via Google.

The account, plastered on the front page of The Fleeting Moment, is a sensation. The paper sells out, especially when the announcement comes later in the day that the execution did not take place and the sentence had been commuted. Tito’s editor is furious, until he realizes that the public has rejected the official story and embraced the fabrication, believing that something so eloquently written and exquisitely detailed must be the truth.

Tito is bemused at this new success, finding it somewhat trivial compared to the torments and ecstasies of his two new loves. But things don’t go so well when he tries to play the same game again. In his review of one of Maud’s performances, his fixation distorts his judgment. He elevates her pedestrian act to celestial heights. It costs him his job.

Why would this review, far less elaborate and flagrant a fabrication than his guillotine story, finally force his editor to give him he axe? Not because the story invented the facts, as had the one before, but because it told the truth. Like all good fiction, it revealed the naked truth of his own yearning and emptiness and need for fulfillment. And if there’s anything a publication is leery of, it’s the truth.

So Tito is cut loose, free to follow his Cocaine, now not the drug but a lover whom he’s named for it, across the world, yearning for an end to his farcical suffering, seeking a form of suicide that is dependable, but not completely so.

As for Pitigrilli himself, he lasted longer than his hero, but he suffered a less enviable fate. As discussed in Alexander Stille’s illuminating afterword to this edition, Pitigrilli enthusiastically pursued his self-serving and (probably) perversely satisfying second career as a spy for the Fascists. He reported on his friends in the Paris avant garde and was instrumental in the imprisonment of many of them. But this well-paying avocation ended when his cover was blown, and by 1938, no longer protected by his powerful friends in the regime, Pitigrilli – who was both half-Jewish and anti-Semitic – became subject to the newly enacted Italian racial laws. Efforts to change his status to “Aryan” did not succeed, and in 1940 he was briefly interned. When Mussolini was overthrown in 1943 and the Germans occupied the country, he fled to Switzerland.

After the war, though he did not face prosecution for his shady dealings with the Fascists, he nonetheless sought safety in Argentina (a favored refuge for many absconded Nazi war criminals, such as Adolf Eichmann), and then Paris. He finally returned to Italy, where – forgotten, poor, and a fervent Roman Catholic – he died in 1975.

Though not of the same stature as other modernist literary collaborators such as Celine, Ezra Pound, or Knut Hamsun, Pitigrilli nonetheless deserves rehabilitation. His bleak and brilliant satire, lush and intoxicating prose, and sadistic playfulness remain as fresh and caustic as they were nine decades ago. His tragic vision of the human condition, expressed through ironic wit and eloquence, distinguishes the great literature of any era. No less than German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder was working on a movie adaptation of Cocaine when he died – of a cocaine overdose – in 1982

Plus, despite the snooty, sometimes forced snark Pitigrilli indulges in, he can write, with seeming ingenuousness, the following:

“Couples…

“Lovers.

“Lovers. The most beautiful word in the world.”

Peter Keough, currently a contributor to The Boston Globe, had been the film editor of The Boston Phoenix from 1989 until its demise in March. He edited Kathryn Bigelow Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2013) and is now editing a book on children and movies for Candlewick Press. He will be introducing a screening of Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty at the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, MA on October 23 at 6 p.m.