Poetry Review: Travel Down “The Golden Road”

Rachel Hadas’s poems present deceptively calm surfaces, like a lake that hides its rich inner life beneath bright reflections of clouds and blue sky.

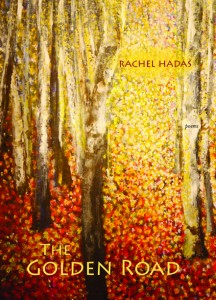

The Golden Road by Rachel Hadas. Triquarterly Books/Northwestern University Press, 80 pages, paperback. $16.95.

By Vincent Czyz

Rachel Hadas has been part of the American poetry scene since her first collection, Starting From Troy, debuted in 1975. In the nearly four intervening decades, she has authored an impressive array not only of poetry but also of essays and translations (from Latin, French, and Greek) as well as a memoir, Strange Relation: A Memoir of Marriage, Dementia, and Poetry, which details the tragic final years of her husband, a composer and professor of music at Columbia University, who was diagnosed with early-onset dementia.

The Golden Road, her 14th poetry collection, is a multifaceted display of Hadas’s sensibilities and the poetic forms she finds in which to express them. Those approaches include, among others, the sestina, ballad, sonnet, and a pantoum, “Host at Last,” suffused with a compelling, kind of backwards-looking longing that is not quite nostalgia. While Hadas is comfortable with rhyme and meter—sometimes so skillfully done it takes a couple of stanzas to notice them—she is equally adept at writing free verse, and there is plenty to be found here.

The poems present deceptively calm surfaces, like a lake that hides its inner life beneath bright reflections of immaculate clouds and blue sky. Dive in, though, and you’ll be drawn by a current of elegy and loss, though I suspect Hadas is equally interested in conveying reconciliation and acceptance. This aura of stoic coming-to-terms surrounds the poem “Nostos” (Greek for return and perhaps etymologically related to nostalgia). Here is the final stanza:

Thirty-some years. A generation.

Over the pool the swallows skim.

As leaves fall, so it is with men.

The great stone mountain bides its time.

A similar sentiment is embodied in “Etymology,” in which Hadas points out that the “Greek word hero is cognate with hour” and closes out the poem with these handsome lines:

A sunny morning followed by noon rain:

Petals scatter over the wet lawn,

Autumn prefigured in the end of May.

Hadas recognizes that each life contains its own death, carries it around like a seed that takes a lifetime to gestate, but the collection rarely embraces despair. As Hadas writes in “Host at Last,” “I used to pine for all that had been lost./But nothing’s ever thoroughly erased.”

Not surprisingly, many of the poems deal with her husband’s illness, “The Onset” being among the most powerful. Addressed to him, the poem begins “When did your illness start?” and goes on to highlight some of their moments as parents raising their son. It ends with a flash of recognition and a crack of thunder: “the last time we looked/each other in the eye and saw a future.”

The balm for the thousand shocks the human condition is heir to is perhaps a sort of Buddhist non-attachment. As Hadas tentatively suggests in “Ballade on Pumpkin Hill,” “Love and let go?” Rather than an absence of emotion, the speaker is talking about cultivating an awareness that permanence belongs to some realm other than this one.

Many of the poems, however, are substantially celebratory. Having visited the Mediterranean and the Aegean numerous times, one of my favorites is “On the Ferry,” in which the narrator sails alone, “saluting light and water through the long bright day/that arcs between the two.” Often the poems bow to acknowledge those quiet moments in which Japanese masters such as Basho reveled. Here is one taken from “Honey.”

Chairs scrape, curtains blow.

Out to the sunny lawn, lilacs in bloom.

The bees build in the crevices of loosened masonry;

I heard the bees from there growl in a hum.

There are also these lovely lines from “Storing the Season”:

For what to do

with misty mornings burning off to blue?

With spangled webs that delicately lace

two blades of grass?

Roaming city and countryside, sea and land, Greek island and New York City park, farmhouse and hospital ward, literature and philosophy, Hadas offers us a book of “unearthed” memories—history and echoes of myth, wise reflections, keen observations, details from the natural world “ambered” in language—all swept along by an autumnal wind. In “Valentine’s Day” the speaker reminds us that “Change is constant” and “There is no other way to move but onward.” Let us then fare forward, travelers.

Tagged: Rachel Hadas, Strange Relation: A Memoir of Marriage Dementia and Poetry