Visual Arts Feature: Museums in the East, Part One

In the first few days of our first visit to China, I was nonetheless unable to keep myself from formulating a hypothesis. In China the distinction between art, artifice and artificiality is not drawn as sharply as it is, at least in principle, in the West.

By Gary Schwartz

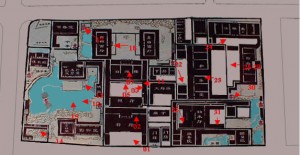

Groundplan and visiting directions of the house of Hu Xue-yan, Hangzhou (1872) Photo: Asian Historical Architecture.

The occasion for my first visit to China, with my wife Loekie, was an invitation to participate in the eighth installment of the annual Beijing Forum, held from November 4 to 6, 2011 on the grounds of Peking University. (We were unable to get a grasp on the principles guiding the use of one name of the city or the other in English.) The theme of the forum, which is convened every year under the motto “Harmony of Civilizations and Prosperity for All,” was Tradition and Modernity, Transition and Transformation. The panel in which I participated was entitled “Artistic Heritage and Cultural Innovation.” One quaff of bromides after the other down the hatch, which nonetheless reminded us of the high purposes to which we were called.

Because we had no intention of flying up and back to Beijing without seeing more of China, we stretched our stay as far as we could in either direction, expanding it to 13 days from November 24 to December 7. Taking advice from friends and a Dutch tour operator, we flew to Hangzhou, were driven after two days to Shanghai via the water village of Wūzhèn, then went on by air to Xi’an and by night train to Beijing. Our guides were qualified mainly for their knowledge of English. They were not up on the latest developments in the arts, and there is much that we missed. In Hangzhou we would have liked to visit the Chinese Academy of Art had we been aware of its existence, but instead we were taken to a number of standard attractions, the China National Tea Museum and the Chinese Traditional Medicine Museum. Having said this, it must be admitted that the National Tea Museum is an outstanding presentation of the subject. Of course it ended with a tasting session and a sales moment.

One of the smaller pavilions in the house of merchant Hu. Unless otherwise noted, all photos credited to Gary Schwartz.

The biggest surprise in Hangzhou was the house of the nineteenth-century merchant Hu Xue-yan (1823–85), which can be called a new museum following its drastic renovation after the year 2000. A tourist weblog states the bottom line about Hu in a word: “He was as rich as a country.” His walled mansion, in the middle of a thriving city, is as big as a football stadium. It reminded me of nothing so much as the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, though the British Prince Regent will not have thought of his palace as the quintessence of all of creation that Hu seems to have been after.

The complex has one feature of a kind that never fails to grab my imagination. One corner has been cut off from the grounds. The guide told us, if I remember correctly, that there was a shop on that spot, where the shopkeeper wanted to stay. Hu let him have his way, although he was warned that nicking the rectangle would bring him bad luck. Fifteen years later he lost favor at court and went bankrupt.

For a number of compelling reasons, I have a deep aversion to Chinese traditional medicine. This was not allayed at the Museum of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Hangzhou, as fascinating and impressive as it is. The museum was founded as a pharmacy in 1874 by none other than Hu Xue-Yan, on his own signature cosmic scale of ambition. Today it is the only officially recognized institution of its kind in the country, producing pharmacies for sale on site and to the trade as well as displaying and explaining Chinese medicine to visitors in a splendid historicizing and now historical building.

The preservation of cultural relics is brought back to first principles in the Museum of Chinese Traditional Medicine by the commendable admonition not to burn them.

Not all the explanations are as candid as they should be. The claim that rhinoceros horn was used “previously” in Chinese pharmaceuticals is belied by the ongoing slaughter of the rhinoceros in Africa, which has reached such a devastating level that total extinction of the animal is a real danger. Traditional Chinese medical practitioners sell crushed rhinoceros horn today, not “previously,” according to The Independent (November 28, 2012), at £35,000 a kilo. An irony attending the tragedy is that the criminal gangs who kill the rhinos must themselves believe in the medicinal efficacy of the horn. Otherwise they would sell for those prices doctored talcum powder that you can buy at the drugstore and that will work just as well in assuring that a woman will bear a son rather than a daughter.

The museum experience in Hangzhou is not limited to institutions bearing that label. Much of what we saw bore out what the prophetic German philosopher Hermann Lübbe, in the 1980s, called the progressive museification of the world. The Chinese have been at it for a long time.

The entire West Lake section, where we stayed, was configured as a scenic attraction in the Song Dynasty (960–1279) and has kept up its semi-museological mission on and off, leading to its recognition in 2011 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site . . . and a motif for the 1 yuan bill. The lake itself is an artefact, as are the park and all its appurtenances. The house of Hu Xue-Yan can be thought of as a collapsed version of West Lake.

Museified too are many Buddhist sanctuaries. The Hall of Five Hundred Arhats of the Lingyin Temple looks less like a place of worship than a sculptural portrait gallery.

Even consumerism is museified in Hangzhou. The main street for tourist items is an evocation of Olde Hangzhou, with ersatz heritage buildings in which to peddle the goods.

Touring in China, the way we did it, follows an itinerary that is signed, sealed and delivered in advance by us, our local travel agent, the Dutch tour operator they bring in, and the Chinese tour operator that the Dutch one works with. Air and train tickets and hotel vouchers are supplied, and at every moment, we have an English-speaking guide and a non-English speaking driver with a comfortable car at our disposal. There is a bit of wiggle room to depart from the master plan but not much. On our last morning in Hangzhou, our guide Grace—the Chinese guides all used English names for the supposed convenience of their foreign charges—suggested that we visit the Leifeng Pagoda before leaving the city and that we sacrifice one of the two destinations where we were going to stop on our way to Shanghai.

The original Leifeng pagoda was built in the year 975 and remained standing, with ups and downs, until in 1924 believers in Chinese traditional medicine, having been told that its bricks, ground into powder, favored male births and cured what ails you, pulled out one brick too many and the edifice fell to the ground. A substitute was constructed on the ruins in 2002, and this is what we see today. It may be a trick of memory, but I do not believe that Grace told this to us on the spot.

The stop on the way to Shanghai was another exercise in museification. The village of Wūzhèn has been mummified into an open-air museum. It fulfills this purpose admirably and provided us with a magical hour or two. Although—or perhaps because—the center of Wūzhèn is now a mere simulacrum of what it was when the town was fully populated, it has a nearly unbearable poignancy. The physical remains have been repaired and restored, with spotty functionality filled in where possible, cleaner than it will ever have been as a living town. Having the place to yourself, as we did, with a handful of other tourists, you are taken in its grip. Imagine to boot that this narrow waterway is a local branch of the Grand Canal from Hangzhou to Beijing, begun in the sixth-century B.C. and at 1100 miles said to be the longest canal on earth. The immediate experience of the place, with its potent local character, is amplified by these dizzying chronological and geographical perspectives.

With only Hangzhou and Wūzhèn to go by in the first few days of our first visit to China, I was nonetheless unable to keep myself from formulating a fargoing hypothesis. That is, that in China the distinction between art, artifice, and artificiality is not drawn as sharply as it is, at least in principle, in the West.

Parts 2 and 3 of “Some new museums in the east,” a notion I apply broadly to include some non-museums and museums that are new only to me, will deal with museums and museified environments in Shanghai, Xi’an and Beijing.

© Gary Schwartz 2012.

The period since the last column was cluttered with obligations, short deadlines and one trip abroad. From November 15 through 20, we were in Scotland. On the 15th, I delivered the keynote address to a one-day symposium on Rembrandt’s painting of the Entombment of Christ in the Hunterian Museum of the University of Glasgow. The painting belongs to the museum and served as the centerpiece of an outstanding small exhibition, with all relevant comparative items.

The symposium, organized by the Hunterian curator Peter Black, was wonderfully relaxed. There were only four talks, and as much time was reserved for discussion as for the lectures. After spending the day after the symposium trying and failing to enjoy Glasgow in the pouring rain, we were relieved to duck into a comfortable hotel room in Edinburgh and to take our time in the coming three days for the Royal Botanical Garden, the amazing Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, and the National Gallery of Scotland on The Mound and at the Modern.

In the month of December, two scholarly articles of mine were published in volumes dedicated to two of my favorite colleagues. For Ildikó Ember, chief curator of Dutch and Flemish paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts (Szépmüvészeti Múzeum) in Budapest, I wrote a contribution on a painting in the museum by the church painter Emanuel de Witte: “With Emanuel de Witte in the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam.” The other one was dedicated to Rudi Ekkart, on an artist of whom even some the editors of the volume had never heard, Gerrit Pietersz. van Zijl. Awaiting the digital offprint, which will be nicer, I am provisionally posting the final page proofs.

Loekie came out with a new publication, an introduction to the catalog of an exhibition on country houses in the Vechtstreekmuseum in Maarssen. 2012 was the Year of the Country House in the Netherlands; the exhibition covers that theme from various angles. In her essay,Loekie sketches the history of gardens and parks in country houses, bringing in the political dimension on which she began to work last year when she planned a trip to English country houses for the Teyler Museum. She was able to show how the transformation of symmetrical formal gardens to picturesque landscape gardens was related to new anti-absolutist ideals in the Whig faction in Parliament. Unfortunately, the trip to England did not materialize, but the ideas it generated have fed into her views on the Dutch garden. The introduction made an impression – after it came out, Loekie was invited by two gardening organizations to lecture on the subject.

Loekie Schwartz, “De geschiedenis van tuinen en parken bij buitenplaatsen langs de Vecht,” in Aanschouw de lusthoven aan de Vecht: achtergrondinformatie bij de gelijknamige tentoonstelling, Maarssen (Vechtstreekmuseum) 2012, pp. 9-32.

At the beginning of March, we will be flying again, to the US west coast, for a lecture on March 9th on Rembrandt and Dürer at Christopher-Clark Fine Art on Geary Street in San Francisco.

Despite the bad news we get on the radio half hour by half hour, I cannot say that 2012 was a bad year for us. And 2013 too is shaping up nicely, with commissions for writing, lecturing, teaching, translating, editing and research from the Netherlands, Germany, France, Switzerland, the UK, and the US well into the year, apart from the commissions I give myself, such as writing more Schwartzlist columns. All I have to do is keep my nose to the grindstone.

Wishing you, dear readers, a full and fulfilling 2013.

Gary Schwartz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. In 1965 he came to the Netherlands with a graduate fellowship in art history and stayed. He has been active as a translator, editor, and publisher; teacher, lecturer, and writer; and as the founder of CODART, an international network organization for curators of Dutch and Flemish art. As an art historian, he is best known for his books on Rembrandt: Rembrandt: all the etchings in true size (1977), Rembrandt, his life, his paintings: a new biography (1984) and The Rembrandt Book(2006).

His Internet column, now called the Schwartzlist, appeared every other week from September 1996 to April 2007 and has been appearing since then irregularly.

In November 2009, Schwartz was awarded the coveted tri-annual Prize for the Humanities by the Prince Bernhard Cultural Foundation of Amsterdam.

Responses always welcome at Gary.Schwartz@xs4all.nl.

gary,

hi.

i’d like to ask a question:

why, besides its horrific trafficking in rhino horn (not to diminish or excuse that in the least) do you harbor a “deep aversion” to traditional chinese medicine ? this is not a hostile but if anything a friendly question. it may not be a simple subject but i would be interested in knowing what you think.

(do the chinese themselves, when given a choice, prefer what some people call science-based medicine over traditional chinese medicine?)

i also have a comment: it’s interesting to read about what you call the museification of chinese culture, and i take your observations to heart. but isn’t the opposite happening as well? don’t artists like ai weiwei and cai guo-qiang represent innovative tendencies that can’t be museified [sic]?

i have never been to china. but as a westerner, interested in chinese art, it would seem that much as china might like to enshrine its past and its aesthetics, there is also a great outburst of creativity.

i look forward to your further posts from the east.

harvey

The answer to your first question is rather personal, involving one devastating and one cynical and disappointing treatment experience in the family. The behavior of patients I do not consider indicative of therapeutic reliability. People patronize all the mutually exclusive medical regimes in the world.

The way Ai Wei Wei and other Chinese artists employ artistic means for social and political purposes can be seen as the opposite of museification, or else as making reverse use of a thoroughfare widened by that process. I am not inclined to be very categorical in judging these things, especially when they involve individuals who are sticking out their necks or even risking their lives in expressing themselves.