Book Interview: Sherwood Anderson — The American Bard of Inchoate Longings

“What Sherwood Anderson knew and understood was the nature of inarticulate lives and what people do when they’re in the grip of strong feelings and words fail them.”

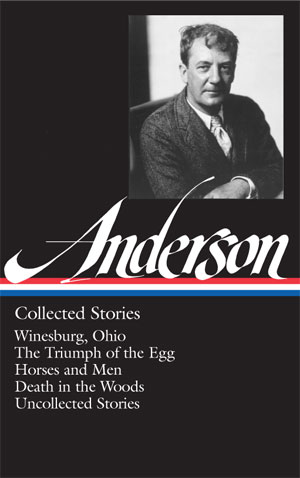

Collected Stories (Winesburg, Ohio • The Triumph of the Egg • Horses and Men • Death in the Woods • Uncollected Stories) by Sherwood Anderson. Edited by Charles Baxter. Library of America, 928 pages, $35.

By Bill Marx

Writing in 1923, critic Edmund Wilson argued that “at his best, Sherwood Anderson functions with a natural ease and beauty on a plane in the depths of life—as if under a diving-bell submerged in the human soul . . .” In his short story collection Winesburg, Ohio and other tales written between the two World Wars, Anderson took a deep dive into the American psyche, detailing the lacerations and consolations generated by the isolation and repression of small town life. Stitching together homegrown colloquialism and modernist minimalism, he wrote some of the finest American stories of the century, triggering a hunger for illuminating the nooks and crannies of interiority that extends from William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway to Raymond Carver.

The unevenness of his output has made Anderson a critical puzzle: Is he a major minor writer? Or a minor major writer? Is he a European-influenced innovator best remembered because of the greater authors he inspired? The Library of American volume collects, for the first time, all of the stories Anderson wrote in his life time, and there is plenty of less than stellar material here. So why read Anderson when he is not at his best? Wilson also observes that even when the writer “cannot save a banal theme from banality, his banality is distinct from the banality of other people.” “At his worse,” Anderson still displays a distinct sensibility, “making his own mistakes . . . in the pursuit of his own ideal.”

As for other reasons to read this indispensable yet hard-to-pin-down writer, I turned to the editor of the volume, Charles Baxter, who is the author of five novels (including The Feast of Love), five collections of short stories, three collections of poems, and two collections of essays on fiction. A National Book Award finalist, he teaches in the Warren Wilson College MFA Program for Writers at the University of Minnesota.

Arts Fuse: H. L. Mencken, no lover of small town life, said of Sherwood Anderson that “no other American writer of today has come nearer to evoking the essential tragedy of American life, or brought to its exhibition a finer or bolder imagination.” How true is that today?

Charles Baxter: Anderson’s view of small town life, particularly in Winesburg, Ohio, was quite dark, as Mencken’s was: he believed that it tended to stifle dissent and encouraged conformity. People in such towns snooped and pried into each other’s lives. The horizons of interest tended to be very narrow and somewhat mean-spirited. In our day, the web has certainly opened up the world to people living in out-of-the-way places, but the habits of conformity and narrowness don’t seem to have changed very much. I have students now in their 20s who are writing about trailer parks and small towns with meth labs, and in these stories, the characters’ lives are damaged in almost exactly the way that Anderson outlined in his tales. People still suffer from poverty, poor educations, and gossip. That hasn’t changed.

AF: Anderson is considered a one-book wonder because of Winesburg, Ohio. What do we learn about the range and limits of his talent from his other short story collections?

Baxter: Winesburg is Anderson’s best-known book, but the novelist Jim Harrison has said that Anderson’s story “Death in the Woods” is the greatest American short story, period. Anderson’s work is certainly uneven, but in his other books, there are wonderfully memorable and eloquent stories such as “The Egg,” “Unlighted Lamps,” and “I’m a Fool.” In our new edition, we’ve printed several of Anderson’s uncollected stories, among them “Sister” and “The Corn Planting,” which I consider a wonderful story and a great rediscovery. What Anderson knew and understood was the nature of inarticulate lives and what people do when they’re in the grip of strong feelings and words fail them. He was not urbane or slick. His stories are sometimes very plain-spoken, even crude. He was not particularly witty, and neither are his fictional characters. But he absolutely understood inexpressible frustration, and he discovered a way to write about it.

Editor Charles Baxter — Anderson’s lack of urbanity, his very clumsiness, can make him quite lovable, and no other writer in American literature knew more about inchoate longings.

AF: Anderson’s short stories dovetail regionalism and European modernism, but it seems to me his roots in Mark Twain and Walt Whitman are also important. In what ways is Anderson a distinctively American writer?

Baxter: Both Mark Twain and Walt Whitman are colloquial writers: they listened carefully to how American talked, and they paid attention to the idioms they used. They were more interested in the idioms of the common people than they were in the more elevated, elegant, genteel verbal styles of the moneyed classes. In that respect, Anderson is a clear descendent from them; he listened to how common people spoke, and even his adolescent speaker in a story like “I Want to Know Why” can be marked as an influence on later writers such as J. D. Salinger.

AF: Has any connection between Winesburg, Ohio and another seminal story collection of the period, Dubliners by James Joyce, been established?

Baxter: Critics and readers have noticed the similarities between those two books for a long time. James Joyce had larger literary gifts, but the project of the two books is quite similar. Both wrote about what Frank O’Connor has called “submerged population groups”—people we would never have noticed if it had not been for the short story collections in which these characters appear. These Dubliners and inhabitants of Winesburg would have gone unnoticed and unrecorded if it hadn’t been for books like these. They are not “important” characters in society’s eyes—they’re not rich and powerful and glamorous—but they’re worth our attention; both Joyce and Anderson insisted on the importance of such nearly-invisible lives.

AF: Anderson’s influence on Hemingway and Faulkner is well known, as is their ambivalence about their mentor. Critic Alfred Kazin refers to Anderson’s “slovenly independence from literary convention.” Why does the writer receive such mixed tributes?

Baxter: Anderson can be a clumsy writer. He knew, and admitted, that he had terrible deficits as an author. The structures of his stories are not always strong because he didn’t always plan them out. He seemed always to have relied on his intuition, which sometimes played him false. He relied too often on naïve characters. But his lack of urbanity, his very clumsiness, can make him quite lovable, and no other writer in American literature knew more about inchoate longings.

AF: What are some of your favorite stories in the volume? Why? And how has Anderson affected your writing?

Baxter: In Winesburg, Ohio, there’s a story called “Paper Pills” about a small town doctor who writes ideas and notes to himself on little slips of paper. He balls them up and throws them into a drawer, where they stay and remain unread. I simply stole this idea and used it in my second novel, Shadow Play. I have always loved “Mother” and “Adventure” (in Winesburg), and both stories understand how the ambition to get out from under the yoke of daily living can turn back in on itself. In many of the other stories, including “Corn Planting” and “Death in the Woods,” there’s a visionary power; you never forget the dramatic images that the stories are built on. There are many others of this type, and every reader will have his or her own favorites. There are many beautiful stories.

AF: It is a given that Raymond Carver was influenced by Hemingway. But Carver and Anderson are the poets of the everyday. Do you see connections between the two?

Baxter: Oh, yes. If you look at Raymond Carver’s story “Fat,” you’ll see that the story is told by a waitress who has had to serve a customer who is enormously fat. That’s part of the story, but the other part of the story has to do with her troubles in explaining to her friend, another waitress, about what has happened to her and how it makes her feel. Words finally fail her. The milieu of a difficult job, a strange intruder, a witness who can’t quite explain what has happened but who must try to explain—it’s straight out of Sherwood Anderson, and I believe that Carver would have been happy to acknowledge that influence if he were still here among us.

Tagged: Charles Baxter, Death in the Woods, Horses and Men, Library-of-America, Sherwood Anderson, The Triumph of the Egg

I was pleasantly tipped off about his edition a number of years ago when I asked LOA why they hadn’t published any of Sherwood Anderson’s works… This collection of short stories is great and comprehensive… I would like to ask if there is any plan to release a collection of Sherwood Anderson’s novels and book of poetry ‘Mid-American Chants’ in a Library of America edition?