Commentary/Review: Book Critics — “Fire the Bastards!” or Judging the Judges

“New York Times” Book Critic Dwight Garner makes salient points about the need for incisive criticism, claiming that too much happy talk denies common sense and undercuts credibility. But the ‘gonzo’ masterwork “Fire the Bastards!” hammers the point home much more memorably.

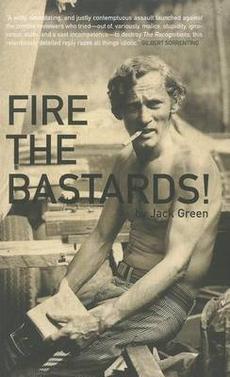

Fire the Bastards! by Jack Green. Introduction by Steven Moore. Dalkey Archive Press, 88 pages, $12.95.

By Bill Marx

For those, like myself, who are evangelists for the cultural value of defining arts criticism as judgments backed up by substantial analysis, it is always good to have some reinforcements. Even if the support smacks a bit of the “with friends like these who need enemies” variety. In a recent piece in The New York Times, book critic Dwight Garner speaks up for the power of discrimination in an arts media (new and old) that he sees as hellbent on yea-saying.

He makes a couple of salient points about the need for incisive criticism, acknowledging the literary contributions of first-rate reviewers (he names Alfred Kazin, George Orwell, Lionel Trilling, Pauline Kael, and Dwight Macdonald), and claiming that too much happy talk denies common sense and undercuts credibility: “The sad truth about the book world is that it doesn’t need more yes-saying novelists and certainly no more yes-saying critics. We are drowning in them. What we need more of, now that newspaper book sections are shrinking and vanishing like glaciers, are excellent and authoritative and punishing critics—perceptive enough to single out the voices that matter for legitimate praise, abusive enough to remind us that not everyone gets, or deserves, a gold star.” Amen to that, though the above critics also wrote powerful reviews of books that they liked. What we need are critics who write with insight and depth about what they love as well as what they find wanting.

Of course, what The New York Times giveth, The New York Times taketh away. I wrote a piece recently that, based on statements made by the NY Times culture editor and its public editor, neither of the poobahs had a strong grip on what substantial criticism of the arts should be. They essentially saw reviewing as a consumer guide service. Garner knows it should (must) be more than that. And, as he admits, Garner is one of the few professional critics left standing amid the tidal waves of opinion about books found on Twitter, blogs, etc, so it is crucial he do a good job at defining and asserting criticism’s value. He has a valuable pulpit—he should use it. And Garner doesn’t, at least this time around.

It doesn’t help that his plea for the need for professional criticism is backed up examples of negative remarks delivered by novelists reviewing other novelists. Edmund Wilson (who would make the admirable critics list) saw the incestuous, back-stabbing corruption of that set-up back in the 1920s. (See his 1928 essay “The Critic Who Does Not Exist.”) Aside from the set-up’s undeniable celebrity value, why does the NY Times host these inevitably back-scratching or back-stabbing match-ups? The publication should hire more independent critics, do its vital part to train and cultivate the kind of reviewers who display the moxie that Garner asks for. But to do that Garner would have to question his bosses and explore icky, sticky issues of conflict of interest in the New York Times Book Review. Aside from its food fight/gossip potential, why is Colson Whitehead picked to review a novel by Richard Ford?

More disturbing is that Garner doesn’t articulate criticism’s value effectively, spending too much of the piece serving up boilerplate hand-wringing about hurt egos and gratuitous insults. We know criticism wounds its victim. Let’s get to the neglected part of the argument — explain the need for independent criticism and assert its indispensable place in the cultural eco-system. Here is where Garner comes the closest to laying out the positive value of the negative: “Marx [Karl, not me, though I agree] understood that criticism doesn’t mean delivering petty, ill-tempered Simon Cowell-like put-downs. It doesn’t necessarily mean heaping scorn. It means making fine distinctions. It means talking about ideas, aesthetics and morality as if these things matter (and they do). It’s at base an act of love. Our critical faculties are what make us human.”

Up until the gauzy sentence about “ideas, aesthetics and mortality” the passage makes sense, though I can’t fully credit any statement about criticism that doesn’t include the word judgment. Criticism is not an opinion, but a judgment (“criticism, as it was first instituted by Aristotle was a standard of judging well” — Dryden). Part of the rub, of course, is what does “judging well” mean? Centuries of debate inevitably follow: for me, judging well means that criticism articulates substantial reasons to back up its verdict—how a critic arrives at his or her conclusions is what matters. So I don’t get Garner’s last two sentences—what do we love? Art? Criticism? Our humanity? All of the above?

About a hundred years ago, Edith Wharton drew a much clearer connection between humanity and criticism. Criticism, she insists in her essay “The Criticism of Fiction,” functions “as instinctively as any other normal appetite. To discuss its usefulness is as therefore as idle as it is perverse to to regard it as a practice confined to a few salaried enemies of art. Criticism is as all-pervading as radium, and if every professional critic were exterminated tomorrow the process would still be active whenever any attempt to interpret life offered itself to any human attention. There is no way of reacting to any phenomenon but by criticizing it; and to differentiate and complicate one’s reactions is an amusement that human intelligence will probably never renounce.” Given the age of Twitter, Wharton’s comment about the irrelevance of professional criticism coming to an end takes on a prophetic angle, but I want to focus on how she rightly sees criticism as a human instinct, an elemental appetite. What is at stake for our cultural well-being is whether we are going to develop this primal yen in serious ways, make it more self-conscious, sophisticated, and pleasurable.

For Wharton, the best criticism deepens, educates, and expands our appetite for art (and for more criticism) because it articulates the reasons and feelings behind our literary judgments. We compare, argue, rethink, and re-view standards of excellence. Reviewing is not just about generating sales: it should excite meaningful, public dialogue about books and their value. (Wharton would add that it also helps the authors, who need superior critics in order to write better books, but for now I don’t want to go down that rabbit hole.) Garner doesn’t invest the act of writing criticism with its own intrinsic significance—for him, and for too many others, reviewing is about supporting the arts or expressing our humanity.

How does first-rate literary criticism, by exemplifying the power of discrimination and analysis, express a love for books? One of journalistic criticism’s most eccentric masterworks, Fire the Bastards!, recently published in paperback by Dalkey Archive Press, provides wickedly ironic evidence of how reviewers, once they master the craft of criticism, pen valentines. The legendary, 1962 broadside was originally published in an underground newspaper (named newspaper) written and published by Jack Green, a pseudonym for Christopher Carilsle Reid.

Most of what has been written about this book (including reviews of the paperback edition) deals with the mysterious career of Reid/Green. (There’s a piece in the Paris Review on the subject). Or the commentaries focuse on Fire the Bastards! as a defense (and exegesis) of William Gaddis’s 1955 novel The Recognitions, which had been greeted by generally incomprehensible and inept reviews when it was published. In three long issues of newspaper, Green, believing Gaddis’s novel to be one of the finest in American literature, takes on the book’s reviewers (fans as well as foes) by name and publication, eviscerating the reviews and the editorial policies of their publications (The New Yorker, The Nation, etc), bringing to the task incomparable logical fury and meticulous attention to detail. A number of his targets remain relevant, in terms of the low expectations and standards for journalistic criticism, the absurdity of ‘capsule reviews,’ etc. He goes about his demolition by way of a idiosyncratic prose that eschews commas, capital letters, and apostrophes. Here is a sample of his prose:

gaddis narrative is never religiose: the relation of religion & antireligious in the 20thcenturyworld

of the recognitions few love and those who do are not loved in return.

the religious experiences are likewise incomplete, marred true love

& and faith are defined by exclusion not by example

but the critics think in stereotypes they’re religiose, believe in strict

separation of church and state their chief dogma, religion is to be

Respected-neither mocked or taken seriously they know only 1

sort of religious novel: waugh-greene, the reformed cynic giving his readers

a sermon because they’re still young and frisky its o sancta

simplicitas when gaddis subtleties collide with critics crude expecta

tions product: a maze of misinterpretations

Fire the Bastards! leads us through an amusing maze of critical laziness and mediocrity, pointing out where reviewers misread or didn’t finish the book, get the plot and quotations wrong, make inane observations, abuse language etc. He is not just scathing on the missteps of reviewers who panned the book: he is hard on “balanced,” mealymouthed critics who refuse to take a stand and on Sunday supplement gushers whose praise issues from the reflex to say something blurb-able, no doubt in order to be safe about a book they couldn’t make heads or tails of.

Many have talked about how Fire the Bastards! anticipates the guerrilla tactics of bloggers and Tweeters of today, though its equal opportunity mode of attack is not only dedicated to defending the merits of The Recognitions but to upholding standards in the craft of journalistic criticism. Reviewers are not doing their jobs well, Green suggests, from the elemental level of being accurate to the more imposing (but still imperative) demand that they come up with sensible reasons to back up their verdicts.

What is not noted about Green’s approach (even in Stephen Moore’s savvy introduction) is that Fire the Bastards! is part of a tradition in which American critics attack the mainstream reviewing powers-that-be, a small, underground force launched by Edgar Allan Poe, who in 1846’s “The Literati of New York” takes on the shortcomings of the major book critics of the time. Poe, being perversely Poe, not only attacked the reviewers’ professional failings but listed personal peccadilloes as well, inviting accusations of slander. Writers such as Ambrose Bierce, H. L. Mencken, Edmund Wilson, and others continued the police action (there are also protests against the gentrification of book criticism in ethnic small magazines that thrived in the late nineteenth century).

The importance of Fire the Bastards! is that it brings this rebellious, meta-critical perspective, propelled by the demand that book critics and editors live up to ethical and intellectual standards, into the world of gonzo journalism. Green’s unorthodox style, personal, stream-of-consciousness tone, brazen linguistic out-thereness serves as a fascinating link between the sardonic scolding of Poe and Mencken and the counterculture, New Journalism hectoring of Pauline Kael (whose career as a critic began in the early ’60s) and Tom Wolfe. He stands in between the split between earnest consumer advice and hoity academic chatter (middlebrow versus highbrow) that was pulling journalistic criticism apart in the ’50s.

What’s more, Green is fighting for something rather than simply attacking flaws, and he brings conviction, thought, and passion to the battle. As Garner argues, Green is affirming his love for The Recognitions by highlighting the limitations of its critics, but he doesn’t tear down criticism in the process—he simply wants to see journalistic reviewing display intellectual integrity and professional competence. The weakness of Fire the Bastards! as a defense of literary critics is the flip side of the book’s strength—it is not, as some of Green’s skeptical critics would have it, that The Recognitions is not the masterpiece he thinks it is, but that Green, the uncompromising advocate, demands all or nothing of book criticism. Granted, reviewers often hide their cowardice in equivocations and the rhetoric of the half-hearted, but books don’t neatly divide into masterpieces or debacles. If the tome in front of the critic isn’t the greatest or the worst of its genre, then criticism must supply a balanced reaction, a notice that patiently discriminates between what is of value and what isn’t and then explains how the critic came to his or her conclusions. Readers can evaluate the quality of the review on that basis.

But Green sees calibration as weakness—it is his thunderous highway or the spineless middle way (think of the hammer-and-tongs reviews of Poe, Mencken, Kael, and their followers). Yet having reservations in a review, delineating points and counterpoints, especially when the heads of other reviewers are lost in the clouds, is also an act of uncompromising strength as well, reinforcing the value of reviewing as an education in discrimination. Still, as one of the gloriously funkier parts of the ongoing debate in American book criticism—which boils down to give ’em hell or give ’em modulation—Fire the Bastards! stands as one of the major achievements of the devil’s party.

And Gore Vidal’s death makes this situation worse.

Well done criticism of a critic, Bill. Many great points here. A writer that praises everyone praises no one. Books should be called out. After the recent dustup at the NYTBR regarding Alix Ohlin’s drubbing by William Giraldi, and the reaction from writers, I double down and would even say poorly constructed criticism needs to be defended. Why? Because idols and cherished ideas need to be challenged. If the criticism is badly conceived, this will become evident soon enough.

For other calls for “arts criticism as judgments backed up by substantial analysis,” check out the conversation in Kent Johnson’s “Some Darker Bouquets: A Roundtable,” itself a substantial response to Jason Guriel’s “Going Negative.”

…and B. R. Myers’s “A Reader’s Manifesto.” Part of which can be found here.