Book Review: The Boston Jazz Chronicles — Indispensible History

Richard Vacca’s The Boston Jazz Chronicles will be a foundational document that other researchers will turn to again and again as they delve into more specific niches of Boston jazz history and unearth as yet unknown artifacts of this era and its neglected body of music.

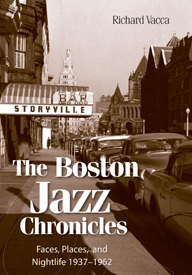

The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife 1937-1962 by Richard Vacca. Troy Street Publishing, 362 pages, $19.95.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5IgNUnDlYZY

By J. R. Carroll

The news this past summer of Chicago tenor man Von Freeman’s passing at the age of 88 was sadly familiar, but not for the obvious reason. Elders of the jazz world inevitably leave us at some point, and Freeman’s career was long and productive and left a significant legacy, not least his son, saxophonist Chico Freeman. What was so familiar was the profile of a musician who wasn’t based in and didn’t spend all that much time in New York: his discography is modest, he didn’t tour very often until well into his career, and the media outside Chicago tended to overlook his achievements, at least until he finally attained national recognition in 2011 as an NEA Jazz Master (but was too ill to attend the ceremony this past January).

The point here is not to memorialize Von Freeman; others have done that with much greater insight into his place in Chicago’s musical life (see this fine remembrance by Neil Tesser). No, the point is that this profile could fit many important musicians who happened to choose not to spend their lives in New York, and more than a few of them have, or had, long associations with Boston.

Chicago is fortunate in the documentation of major chunks of its jazz history by way of two magnificent bookends, William Howland Kenney’s Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History, 1904-1930 and George Lewis’s A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music. Until recently, though, much of Boston’s jazz history lay within yellowed news clippings from extinct publications, personal collections of memorabilia, microfilm images, photo archives, and, above all, the memories of a rapidly dwindling population of musicians, club owners, writers, and jazz fans.

Now, at long last, someone has taken on the colossal task of sifting through and trying to make sense of all these scattered facts and artifacts, and the result is nothing less than the first serious historical survey of jazz in this city. Make no mistake: Richard Vacca’s The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife 1937—1962 is, to quote Joe Biden, a Big Freaking Deal.

I can only imagine what confronted Vacca when he decided to expand what began as a tour guide to historic jazz sites in Boston into a full-blown history of a critical quarter-century of music making in this city. On the one hand, there was a plethora of detail—albeit widely scattered—concerning the comings and goings of often unfamiliar and long-deceased individuals and the similarly departed performance spaces they operated or in which they performed. This mass of discrete factoids desperately needed organization, and Vacca has done a yeoman job of bringing a degree of order to this unruly body of information.

On the other hand, the sounds that emanated from these musicians and venues were, with limited exceptions, woefully underdocumented in audio artifacts. New York was the locus of the recording industry on the East Coast, and record dates were scarce for musicians who didn’t live there. Boston had a handful of scrappy local labels—Crystal-Tone, Motif, Storyville, and Transition Records—and we have them to thank (along with the labels that have reissued them in recent years) for much of what we can hear today of the big bands of Sabby Lewis, Nat Pierce, and Herb Pomeroy, and of small groups led by Charlie Mariano and Serge Chaloff. But until the day some long-lost 78 or broadcast transcription surfaces, the music of pivotal figures like bandleaders Joe Nevils and Jimmie Martin—whose Boston Beboppers included Jaki Byard, Sam Rivers, Gigi Gryce, Joe Gordon, and Alan Dawson, among others—is as lost to us as Buddy Bolden’s.

Faced with this imbalance in documentation, Vacca made some wise decisions, as he lays out in the preface:

Boston has a rich jazz history, and I wanted to uncover it and bring it to life. I had no intention of joining the tedious debate about what jazz is and who is entitled to play it, and not being a musician myself, I wasn’t going to try to interpret the ambitions and motivations of those who played the music 60 years ago. I saw my role as that of reporter, not critic, and my intent was to leave it to others to intuit deeper meanings.

Vacca is too young to have significant personal memories of most of this period, and so the narrative successfully avoids getting mired in the nostalgia that might have claimed an older author. Boston had no shortage of colorful characters, some with tragic endings, and Vacca doesn’t totally ignore them, but this is a history, not a personal memoir. He is also fastidious about not including rumors and hearsay, particularly where criminality (organized or otherwise) might have been intimated but hasn’t been persuasively established. (In this he already adheres to a higher standard than far too many current-day practitioners of what is loosely termed “journalism.”)

The decision to open the book in 1937 makes sense. Until the past decade or two, even the history of jazz in New York and Chicago had serious holes, and the period before the mid-1920s was almost terra incognita. (Who really knew very much about James Reese Europe or Wilbur Sweatman or even the performing and recording careers of W. C. Handy or Bert Williams?) Similarly, 1962 marked the end of a period in which jazz flourished in Boston, to be followed by lean times in the 1960s as venues dried up and musicians left for New York in search of better opportunities.

Given that Vacca’s point of entry into what became seven years of research was his interest in the literal landscape of Boston jazz as it existed between 1937 and 1962, it’s unsurprising—and perfectly sensible—that geography became the book’s organizing principle. Groups of musicians were associated with individual clubs and ballrooms (and their owners and promoters, whose relationships with the musicians were sometimes less than harmonious), and these venues tended to cluster in specific neighborhoods. (The book includes many fascinating photos of these vanished institutions and their surroundings, as well as the memorable individuals who owned, managed, booked, and performed in them.)

Almost inconceivable today, many clubs had house bands that stayed in residence performing nightly for months and weekly for years, and so association with a particular band meant association with its host club as well, for better or worse. Pianist Dean Earl performed at Little Harlem and then at its successor, Eddie’s Musical Lounge, for some two decades. Pianist Sabby Lewis and his band were at Steve Connolly’s Savoy Cafe from 1943 to 1946. Fellow pianist Al Vega and his trio held forth at the Hi-Hat Barbecue from 1950 to 1953. The house sextet of the Stable—trumpeters Joe Gordon and Herb Pomeroy, tenor saxophonist Varty Haroutunian, pianist Ray Santisi, bassist John Neves, and drummer Jimmy Zitano—anchored the club’s schedule from late 1954 through well into 1958. (The club and its band, by the way, were the inspiration for Benny Golson’s “Stablemates.”)

Radio and later television also were outlets for jazz artists, and it’s to Vacca’s credit that he doesn’t overlook their role in making live performances available to listeners in Boston and sometimes nationwide. The Boston media had its own celebrities, one of whom, “Symphony Sid” Torin, spent five years here at WBMS after gaining fame in New York with his live broadcasts from Birdland. (Pianist Sabby Lewis, who had wound down his big band in the eary 1950s, also spent the same five years at WBMS as a disk jockey.)

Of course, all of the preceding mutated over the course of a quarter century for reasons that were part economic, part demographic, and, to a considerable extent, political.

I wasn’t born in Boston, didn’t grow up here—indeed, didn’t take up residence here until 1986—and the most recent of the events documented in Vacca’s book occurred when I was a 12-year-old in northwest Pennsylvania. For other readers similarly bereft of Boston origins, I would urge you to jump immediately from the preface to the appendix “Snapshots of a City,” which provides a capsule introduction to the history, sociology, politics, and media landscape of Boston in the mid-twentieth century.

Even if you’ve never set foot in Manhattan, you know the names of the neighborhoods where musical venues clustered: Harlem, 52nd St., Greenwich Village. But what about the South End? Copley Square? the Theatre District? the ballrooms that once surrounded Symphony Hall? Even if you’ve lived your entire life in Boston, you will still find yourself flipping back to the four crucial maps of Boston jazz clubs, ballrooms, and theatres that open the book proper.

A caveat: If you weren’t living in Boston during the tsunami of urban renewal (or urban removal, as some have termed it) that took place between the mid-fifties and mid-seventies, these maps will prompt more than a little head-scratching. Some neighborhoods, like the West End and the New York Streets section of the South End, were essentially bulldozed out of existence. Others, like Chinatown, South Bay and Bay Village were chopped up by highway projects; for example, compare the modern map below (click to enlarge) with Vacca’s map (on page 8) of the Theatre District in the 1940s:

The dance palaces, of course, are long gone, and, with one shining exception, the clubs have vanished as well. The maps also drive home the fact that, aside from Boston’s South End and Inman Square in Cambridge, the Boston area no longer has anything resembling jazz “districts” where one can walk from club to club taking in multiple performances in the course of an evening.

As I made my way through Vacca’s factually dense text and perused these maps over and over, though, a nagging question repeatedly arose: Where’s Roxbury—the heart of Boston’s African-American community—in this story?

It turns out that this is the wrong question. Instead, I should have asked: Where did the majority of African Americans in Boston live between 1937 and 1962? The answer, for much of this period, is Boston’s South End, and that, indeed, is where a notable number of Boston’s important jazz venues were located—and where the last survivor of that era, Wally’s Cafe, still offers live jazz seven days a week.

The history of race relations in Boston is complex and at times has been fraught with conflict, and Vacca doesn’t shy away from dealing with these issues as they arise in the course of the book. No, like most cities outside the South, Boston didn’t enshrine Jim Crow in its legal codes, but that doesn’t mean there weren’t unofficial barriers that could be every bit as intractable.

As in comparable cities, Boston had two separate locals of the American Federation of Musicians—one white (Local 9), one black (Local 535). The Local 9 members got the better-paying hotel and theatre orchestra jobs, while Local 535’s musicians by and large had to be content with club gigs; it wasn’t until 1970 that the two finally merged.

In Boston at that time, there was genuine fear—probably not entirely unjustified—on the part of owners and operators of larger venues concerning the incendiary potential of racially mixed audiences. Even the city’s premier ballroom, the Roseland-State, effectively partitioned its schedule into separate nights for black and white audiences. (The owners of the Roseland-State, Charlie and Cy Shribman, otherwise did pretty well by African-American musicians, hiring and promoting the bands of Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford, and countless others all over New England.)

The powers-that-were in Boston certainly contributed to this fear through their control of licensing and their very real power to shut down a venue that incurred their wrath. Racially mixed audiences, like those at Southland, Little Harlem, Little Dixie, and the short-lived Royal Palms, were more likely to draw the disapproving eye of the authorities, and even venues that kept a low profile could still run afoul of a cop with a bad attitude. Some clubs, like Ben and Jack Ford’s Tic-Toc, often seated black and white patrons separately, particularly when the level of volatility was jacked up by the presence of hard-drinking servicemen on weekend leave.

In the postwar era, integrated audiences became more and more the norm, especially at the major clubs like the Savoy Cafe, Storyville, the Stable, and the after-hours Pioneer Club. Dixieland clubs were outliers, with their nearly all-white audiences, but this was largely because African Americans in Boston, particularly the younger generation, had little interest in music of the 1920s, especially when played by white wannabes for houses of frat boys. (In many instances, though, the bands performing were integrated.)

In too many venues, discrimination extended to booking policies as well—the Raymor Ballroom never hired a black band in the entire time of its operation. Slowly, though, the barrier broke down in the face of the indisputable genius and box-office draw of the musicians. The after-hours Theatrical Club’s normally whites-only policy on the bandstand gave way after an irrefutably successful trial performance by Fats Waller in 1936. Drummer Chick Webb’s orchestra, with a very young Ella Fitzgerald, broke the barrier at the Flamingo Room in 1938, and so it went with club after club.

Progress was even slower on the ownership front. There were no black-owned venues until Joseph “Wally” Walcott opened his eponymous nightclub in the South End in 1947, and no black-owned record labels until Tom Wilson started Transition Records in 1954.

Despite the barriers, musicians of both races who wanted to to play together usually found a way, especially in jam sessions. In the 1940s the Ken Club in the Theatre District ran Sunday afternoon jams that attracted musicians, black and white, not only from Boston but on day trips up from New York. After the war, the South End’s Hi-Hat Barbecue, across from what was then Wally’s Paradise, became a magnet for mingling modernists from the Nat Pierce and Jimmie Martin bands.

Gradually, the integration of ensembles became more the rule than the exception. For quite a few years the main arranger for the Sabby Lewis orchestra was the white saxophonist Jerry Heffron, and the smaller bands of saxophonist George Perry and trumpeter Frankie Newton were comparably integrated. By the 1950s, the barriers had pretty much fallen away, especially in a thoroughly modern ensemble like Herb Pomeroy’s big band.

Boston musicians faced—and still face—a more intractable problem (shared somewhat with Philadelphia) that Chicago and most other cities with significant jazz scenes didn’t: proximity to New York. As far back as the 1920s (with artists like Johnny Hodges, Harry Carney, and Charlie Holmes), a persistent and somewhat pernicious pattern emerged: at their earliest opportunity, Boston musicians, instead of enriching the local jazz scene, would relocate to New York—a phenomenon well documented by Vacca—where opportunities were perceived to be greater. (Of course, so was—and is—the competition.)

The flow of musicians wasn’t entirely in one direction, though. In 1937 bandleader and vocalist Blanche Calloway, Cab’s elder sister, settled into what became a two-year residency headlining shows at Boston nightclubs, and from 1939 to 1941 she regularly toured New England fronting the Alabama Aces, a well-regarded band led by alto saxophonist Joe Nevils and based at the Little Dixie club.

Even more important was the influential regular presence, beginning in 1942, of Frankie Newton, an elegant, lyrical trumpeter who had a facility with mutes. Although based in New York, Newton became a fixture at Sunday jam sessions in Boston, periodically played extended stints as a leader, and continued his association with the city for a decade. (Newton also mentored a couple of notable young Boston jazz enthusiasts, Nat Hentoff and George Wein, who ultimately joined the migration to New York.)

The year 1942 was significant in other respects. Although the Cocoanut Grove wasn’t a jazz club, the calamitous fire there that claimed almost five hundred lives resulted in a total shutdown of all night clubs for months while they underwent safety inspections. It was also the year that the American Federation of Musicians began what became a two-and-a-half-year nationwide strike against record companies that ultimately won the right to royalties; unfortunately, it also resulted in a recording ban that left a catastrophic gap in the documentation of jazz history—including Boston’s—at a time of great artistic ferment.

That year also saw the departure to New York of Boston Herald columnist George Frazier, a flamboyantly pugnacious writer who had been the fledgling Down Beat magazine’s Boston correspondent since 1936. Frazier was effusive in his praise of the handful of Boston musicians he liked, most notably trumpeters Frankie Newton and Bobby Hackett, but in general did the city no favors with his chronic, caustic mockery of the Boston music scene. Still, with Frazier gone there was no one covering Boston jazz on a regular basis again until the late 1950s, although the gap was somewhat filled by the Boston Traveler‘s entertainment columnist, George Clarke (sort of a Boston version of New York’s Earl Wilson), who was favorably disposed to certain jazz performers, particularly Sabby Lewis (who returned the favor in 1949 with the tune “Clark’s [sic] Idea”).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9QTAxwhYkEs

In Boston as in the rest of the nation, the war years were a subdued and somewhat nostalgic period. Jazz continued to evolve, but for a time its ranks were diminished by the absence of many younger musicians who volunteered for or were drafted into the military. The luckier and more talented ones succeeded in spending a portion of their service playing in military bands, where at least occasionally they would get a chance to sink their chops into a jazz chart; the real payoff, though, would come after the war.

With the passage of the G.I. Bill, veterans gained access to funding that allowed them to pursue higher education. Musicians readily took advantage of this benefit, and Boston, with its prominent conservatories, became an important destination for formal training. Although many ultimately left for New York and elsewhere, from the late 1940s through the 1950s the Boston jazz scene was enriched by many gifted young (and not-so-young) musicians who decided to stick around and helped to form the critical mass of performers who made the fifties something of a golden age for Boston jazz.

Appropriately, Vacca devotes an entire chapter to Boston’s music schools, and provides extensive profiles of the New England Conservatory’s Department of Popular Music (which existed from 1942 to 1958) and of Schillinger House, which in 1954 changed its name to the Berklee School of Music. Surprisingly, though, the chapter contains only a fleeting reference to the Boston Conservatory (although it does get mentioned in passing in other portions of the book). This is puzzling, given that its students included Sam Rivers and Gigi Gryce, both of whom benefited from the open-minded encouragement of composer Alan Hovhaness, who was on the Conservatory’s faculty at that time. (The young Quincy Jones also studied there, though not with Hovhaness).

This brings up the book’s other perplexing gap: pianist and composer Cecil Taylor, who came to Boston in 1951 and spent the next three years studying at the New England Conservatory, an experience made bitter by having been blocked from admission into the school’s Composition Department (although he did gain the sympathy of one faculty member, saxophonist Andy McGhee, who hipped him to Jaki Byard, Gigi Gryce, Sam Rivers, Charlie Mariano, Herb Pomeroy, Serge Chaloff, and others on the cutting edge of Boston jazz). True, from the perspective of Boston musicians, Taylor passed through the jazz scene leaving scarcely a ripple (as he does in Vacca’s book), but his lengthy profile in writer A. B. Spellman’s classic Four Lives contains an extensive recollection of his time in Boston that includes significant memories of trumpeter Joe Gordon and pianists Jaki Byard, Dick Twardzik, and Sam Broadnax.

The “baby boom” years following the end of World War II were the period when a genuine jazz scene finally gelled in Boston. As in New York, there was a general shift to smaller ensembles, albeit with opposing impulses. Bebop emphasized new complexities in both the vertical and horizontal dimensions of music, with a premium on virtuosity and the ability to sustain lengthier solos than were generally accommodated by the big bands of the swing era. The counterreaction, the so-called moldy figs, idolized a semimythical golden age of jazz that came to an end with Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Peppers; at its best it brought about a renewed interest in ensemble improvisation and in old masters like Sidney Bechet, but at its worst it produced the dubious nostalgia of “Dixieland.” Racing past both camps, under the radar of both the mainstream press and partisan critics, were the jump blues bands—exemplified in Boston by Paul “Fat Man” Robinson—that were in the process of mutating into rhythm and blues. Of course, these distinctions meant a lot less to the musicians, and many moved comfortably among all these styles, more interested in the gigs and in the diverse musical challenges than in the labels attached to them.

Again, as in New York, a number of the jazz clubs focused on one or another of these genres, attracting a particular audience that influenced the character of these venues. Beboppers found a congenial home initially at the Melody Lounge, located in the blue-collar suburb of Lynn, which had a surprisingly lively jazz scene in the postwar years; later, the center of gravity moved to the Stable in Copley Square and the resident sextet that formed the core of Herb Pomeroy’s big band.

Their more commercially successful Dixieland nemeses (along with, to be fair, the authentic originators and disciples as well) held forth at the Copley Terrace on Huntington Avenue, George Wein’s Mahogany Hall (in the Copley Square Hotel), and the South End’s Savoy Cafe in its later years.

Jump blues could be heard all over town, but particularly at the Knickbocker Cafe (“Fat Man” Robinson’s home base in the Theatre District), later renamed the Stage Bar. And musicians of all idioms (except the lamest of Dixielanders) were regulars at Wally’s.

The postwar years saw not only a significant ramp up in musical activity but also something of a revival in media support for Boston jazz. Print journalists like Nat Hentoff, John McLellan, and “Jazz Priest” Fr. Norman J. Connor doubled as jazz hosts on Boston radio and television. Even George Wein, when he wasn’t busy starting the Newport Jazz Festival and managing Storyville Records and the jazz club of the same name, found time to pen a weekly column for the Boston Herald.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bMzUBYXY8PE

Perhaps there was and is no “Boston sound” per se, but I think a case can be made for a distinctive tradition of writing and arranging for medium- to large-scale ensembles. The roots of this are in Sabby Lewis and his peers, but it was really in the 1950s that bandleaders like Herb Pomeroy and Nat Pierce and composer/arrangers like Jaki Byard, Gigi Gryce, Charlie Mariano, Boots Mussulli, and others came to the fore. Although many of them (with the crucial exception of Pomeroy and his long association with Berklee and the MIT Festival Jazz Ensemble) moved on to New York and elsewhere in the 1960s, the seeds had been sown for a flowering of big and biggish—and still active—bands in the 1970s and 1980s: the NEC Jazz Orchestra (1970), the Harvard Jazz Bands (1971), the Aardvark Jazz Orchestra (1973), the Jazz Composers Alliance Orchestra (1985), and Either/Orchestra (1985), among others. Even the smaller ensembles of the fifties shared their larger peers’ proclivity for original compositions with contrapuntal lines and interesting instrumental colors and voicings; today groups like the New World Jazz Composers Octet carry on this tradition through their emphasis on works by Boston-area composers.

All this activity began to evaporate in the early 1960s, and, as thoroughly as he documents the upswing in Boston jazz, Vacca also recounts in detail its disintegration. The Stable and Storyville closed up shop, as did Transition and Storyville Records. NEC’s Department of Popular Music shut down, and jazz wouldn’t return to the curriculum until Gunther Schuller took the reins of the Conservatory in the late sixties. O’Connor and Wein relocated to New York (Hentoff had made the move a decade earlier) and McLellan departed the jazz media; other journalists and broadcasters, even if they had wanted to stick around, soon found they no longer had any newspapers or radio or TV stations interested in employing them. Dick Twardzik, Serge Chaloff, and Joe Gordon were dead; Charlie Mariano, Gigi Gryce, Jaki Byard, Sam Rivers, and even drum prodigy Tony Williams had split town for the brighter lights of Manhattan. But Alan Dawson, Herb Pomeroy, Ray Santisi, and others found a long-term home at Berklee, and the indefatigable Al Vega would keep performing for another half century.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FYCYu3-PyWk

It was difficult to make a living as a full-time jazz musician in a place like Boston. There wasn’t enough work even in the best of times. To keep body and soul together, the jazz musicians worked in society bands, floor show bands, dance bands, theater orchestras, and any number of general business situations.

Sound familiar? Vacca’s description of the jazz performer’s lot in the period covered by this book is echoed by what I’ve heard from musicians and personally observed in recent times here in Boston. Didn’t this also apply to musicians in New York and Los Angeles? Yes, but these cities also were centers of the record industry, radio and television, musical theatre, and movies, which also employed many musicians and occasionally even allowed them to play some actual jazz. (Today, radio orchestras—at least in the US—no longer exist, but the job gap they left behind has been filled somewhat by music for video games.)

Boston in the past fifteen years has seen drastic reductions in jazz coverage in its major daily and weekly newspapers; on commercial radio the last bits of jazz have vanished entirely, and it has almost disappeared from major public stations (that is, WGBH—WBUR ditched its jazz ages ago), leaving college radio (especially Harvard’s WHRB and MIT’s WMBR), online publications (like the Arts Fuse), and music streaming sites (like the Berklee Internet Radio Network) to take up the slack to the extent they can.

Even if today’s major jazz venues in the Boston area have hung on (by their fingernails, in some cases), the reduction in media exposure for jazz artists has made a tough row even harder to hoe, and it seems like a month rarely goes by without hearing about some important local musician packing up and moving to New York, or even out of the country altogether. Will the Boston jazz scene in the second decade of the twenty-first century look the way it did in the 1960s? We all hope not, but the indicators are troubling, and Vacca’s book gives weight to this perspective.

Believe it or not, this review only scratches the surface of the wealth of information and observation in The Boston Jazz Chronicles. Vacca’s clear and accomplished prose packs so much content into these pages that almost anyone else will find it a steep challenge to hold it all in mind at one time. The book does have a respectable index, but it doesn’t—couldn’t—come close to covering everything, and my hope is that at some point a searchable digital version of the full text will become available.

Is The Boston Jazz Chronicles the final word on the city’s scene during the swing and bebop eras? No, but I absolutely believe it will be a foundational document that other researchers will turn to again and again as they delve into more specific niches of Boston jazz history and unearth as yet unknown artifacts of this era and its neglected body of music. Every page of this book has the potential to jog some reader’s memory and lead to as yet undiscovered treasures of the city, and we will all have Richard Vacca to thank.

I was very impressed by The Boston Jazz Chronicles because even though I was a participant in the Boston music scene from 1953 through 1962 I learned a lot of things about that period that were not previously known to me. And about virtually everything that Mr. Vacca wrote with which I was familiar his accuracy was amazingly sharp. This book will be a valuable and trusted resource for any who are wise enough to pursue it.