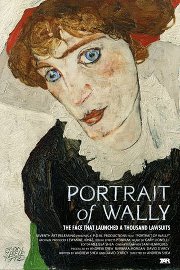

Film Review: “Portrait of Wally” — Art As ‘Holocaust Loot’

Portrait of Wally makes for a wonderfully engaging documentary about art and postwar intrigue with stakes on both a personal and global scale.

Portrait of Wally. Directed by Andrew Shea. Presented by the Boston Jewish Film Festival. At the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, June 28 through July 1.

By Tim Jackson

I recall my amazement in 1997 seeing Egon Schiele’s paintings and watercolors at a landmark show mounted at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Many of the paintings and watercolors were overtly sexual, bordering on inappropriate (lots of prepubescent figures), and obsessed with death and decay. This vision of Eros and Thanatos was beautifully painted, full of sinuous lines, haunted faces, mottled textures, vivid colors, intimate body parts, and haunted eyes. Seeing this collection was a revelation about an artist about whom I was barely familiar.

The paintings at that show were on loan from the Leopold Museum collection in Vienna and provide the high stakes background for Portrait of Wally, a new documentary that dramatizes the amazing story of the titular Schiele painting and its connections with postwar intrigue. The painting’s seizure by U.S. Customs and the ensuing legal case generated a highly public debate in America about stolen art and, more specifically, the ethical dilemma of a major museum’s relationship to “Holocaust Loot.”

Before this controversy, museums in Europe had been the focus of art stolen or confiscated by the Nazis during the war. In the late 1980’s, Hector Feliciano, a Puerto Rican journalist (who graduated from Brandeis in 1974) started to investigate looted art. His book Lost Museum: The Nazi Conspiracy to Steal the World’s Greatest Works of Art (initially refused by publishers) traced the provenance of stolen, post-war art, which led to thousands of works being integrated back into museum collections. In 1996, Austria published a list of looted objects, and eventually the government auctioned off unclaimed art works to the benefit of Holocaust survivors. Published in 1994, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War was adapted into an acclaimed film in 2006. Both document the Nazi destruction and appropriation of European art during the war.

Portrait of Wally comes off as a detective story full of surprising machinations and compelling historical facts. The Schiele painting was seized by Nazi collaborator Friedrich Welz from its owner, Lea Bondi Jaray, in the late 1930s. It was recovered by American troops in 1947 and delivered to the Austrian Federal Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments. But Jaray died in 1961 without ever regaining ownership. After many twists and turns in ownership, the painting found its way into the possession of Dr. Rudolf Leopold, after whom the Leopold Museum is named. It is from that museum that the collection arrived at the MOMA in New York in 1997. Leopold’s obsession with Schiele’s art was narcissistic, and his activities were possibly illegal. Leopold sought to be, according to author Sophie Lillie, “the person who made Schiele into what he was, and in so doing completely blocked out the history, the legacy, and ultimately the names of his pre-war collectors.”

The family and heirs of Lea Bondi Jaray had no idea this major work of art, which had once been owned by their mother, was being exhibited at a major U.S art museum. Eventually, a grand jury issued a subpoena to keep the painting in New York until an investigation could be completed. The film covers the story of the ferocious conflict among governments, museums, curators, and politicians. This was the first time a major U.S. museum had been caught in such an embattled contest regarding stolen postwar art. The debate revolved around strongly voiced opinions on the ethics and liability of ownership verses the freedom of major institutions to mount significant exhibitions without risk. The story was widely covered, and disagreements aired throughout the media including in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, NPR, 60 Minutes, and The New Yorker.

All this makes for a wonderfully engaging story with stakes on both a personal and global scale. The case raises questions about historical memory and national responsibility, and the documentary uses archival footage and news conferences to skillfully set up the various power struggles. Director Andrew Shea and co-producer, art critic David D’Arcy, detail the story through pointed interviews with the family, legal experts, and journalists, including 60 Minutes correspondent Morley Safer. Gary Lionelli composed his score as if he was providing music for a suspense film.

The conversation about the ethical responsibility of museums concerning stolen art is much more common today. National ownership of cultural property and treasures does not have to stifle the freedom of museums to display art from around the world. The case of Schiele’s picture of his 17-year-old mistress, Walburga (“Wally”) Neuzil took 13 years to resolve. The heirs wanted proper ownership restored; the museum wanted the painting to hang alongside Schiele’s self-portrait. Even if you already know the outcome, seeing and hearing how the case was finally resolved makes for a moving story.

Underneath all the intrigue is the complexity of Schiele’s own life and art. His work is disturbing and well ahead of its time. He died at the age of 28, leaving no heirs and a unique body of expressionist portraiture. So much was written at the time about the show that it is worth going back and reading some the effusive writing from The New Yorker (Simon Schama) or The New YorkTimes (Holland Cotter). Here is a sample from Cotter’s 1997 Times review:

A 1910 drawing of a pregnant woman in the show might easily be a study for a Cindy Sherman picture. His offbeat palette (lilacs, vermilions, velvety browns) and liquidy brush style finds an echo in the work of Elizabeth Peyton, his contorted female figures in that of John Currin. His exhibitionist glamour probably contributed as much to the heroin-chic of recent fashion advertising as it did to the louche, companionable underworld of Nan Goldin’s photographs . . . In self-portraits he tried on a number of guises: tousle-haired innocent, scowling grotesque, masturbating bad boy, quasi-religious martyr hamming it up in solitary Pietas and crucifixions. He usually appears naked, self-exposed, but it’s a curious version of candor, theatrical rather than psychologically revealing. The same might be said of his depictions of women, which form the largest chunk of his prolific output. Whether his subjects were anonymous patients in a Viennese hospital or studio models, his red-haired girlfriend Wally Neuzil or his wife, Edith Harms, they all come in for more or less the same treatment. Corpselike in pallor, they are viewed from above or in crotch shots, wearing boots and lifting their skirts. Often they assume the convulsive poses associated with fits of hysteria.

The film begins by giving the audience a close look at Egon Schiele’s work. And this is just the beginning of the fascinating story.