Jazz Review / Commentary: David Sanborn at Scullers – The Craftsman Cometh

Art with a capital A has been put on such a pedestal that Craft with a capital C has been downgraded to a shabby or rustic sort of activity of which the practitioner should be a little ashamed. ’Tain’t so.

By Steve Elman

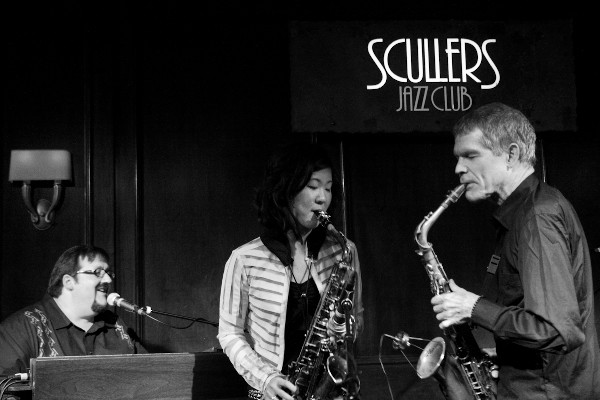

Saxophonist David Sanborn at Scullers — he has always wanted to make music that delivers a punch. Photo: Kristophe Diaz

I first saw David Sanborn when he was 22 or 23, playing alto with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in Binghamton, New York. At the time, I thought, “I gotta pay attention to this guy.” Sanborn turns 67 this year, and he’s become more of a presence in music than I ever anticipated. His status has vastly surpassed that of Butterfield, or Hank Crawford, or David “Fathead” Newman, the saxophone journeymen who are among his enduring heroes and influences, or of Johnny Hodges, Louis Jordan, Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, or Cannonball Adderley, who all practiced the soulful style of jazz that he inherited.

To me, his career is all of a piece, but those who came to him on the strength of his early commercial recordings (unfairly typed as “smooth jazz”) or his funky, dance type stuff (often guided by bassist Marcus Miller), or his late-night TV show appearances, or his film score work, or the very ubiquity of that keening, X-Acto Knife sound he made his own, might be forgiven for thinking that he had “gone commercial” or “come back to jazz” at various points in his career. David Sanborn, is now, and always has been, a master craftsman, and I admire him for it.

Art with a capital A has been put on such a pedestal that Craft with a capital C has been downgraded to a shabby or rustic sort of activity of which the practitioner should be a little ashamed. ’Tain’t so. Art is the name we give to activities that are beautiful but essentially useless, things that enrich us by their very existence. Craft is creative activity in service to a function. Pretentious art is no virtue, and excellent craft is no vice. Nearly every great artist begins as a great practitioner of craft, and almost every great crafter produces something that approaches the level of art. The essential difference between the two is purpose.

Sanborn has always wanted to make music that delivers a punch, music that you can dance to if you choose, music that speaks to the heart and the libido first and only incidentally converses with the brain. In short, he has striven to make music with soul. This is a noble purpose. If his work glorifies the sunshine and romanticizes the shadows, if it chooses to celebrate life and helps us to forget about death, what’s wrong with that?

Does he have technique? And how; he can stand toe-to-toe with any of the great saxophone virtuosi, and he could best any of the so-called smooth jazz players in a cutting contest using only half his fingers. Is he a stylist? Absolutely; as Charles Mingus said of Charlie Parker, if he were a gunslinger, there’d be a lot of dead copycats. Does he have an inimitable, personal sound? He is as distinctive on the alto and as immediately identifiable as Johnny Hodges was on the same ax; he is as much a definite personality on his instrument as was Stan Getz on tenor or Horace Silver on piano or Art Blakey on drums.

He understands that drama in a solo is not just about working up to a fever pitch and stopping; he forges ahead, eases back, caresses a note, slaps the next phrase around, all the time working, working to a logical conclusion. He has mastered space in his music; he gives you time to think about what he’s just played and gives himself time to think about what he wants to play next. And he’s worked hard to achieve exactly the sound he wants: he’s hard and hot as a blues shouter, purposefully employing wide vibrato and sour-sweet glissandi to punctuate and shape his phrases.

Incidentally, that sound fills a room, amplified or not. The acoustics at Scullers are such that Sanborn doesn’t need reinforcement to be heard, but when he brought his organ trio to Boston on February 10 and 11, he brought his own sound man as well. I suspect the reason he did so is that he cares very much about the balance within his band. His recordings are all produced with great care, and a good craftsman wants his live listeners to have the benefit of professional ears massaging the room sound. Obviously, Sanborn can afford to carry those ears on tour, but the fact that he chooses to do so when his group is so small is another mark of a great craftsman.

I would never fault house PA staff—their jobs are thankless, all too often, and Scullers usually has good folks behind the board. But a professional who knows each tune and knows the players’ idiosyncrasies can compensate for the ebbs and flows of the music in a way that a local crew simply can’t. This served the other members of the trio very well—Joey DeFrancesco uses almost all of the swells and whispers available to the Hammond B-3 player (though there was no Leslie cabinet at the show I saw), and Byron Landham has an admirable sense of dynamics. Neither of them was ever too loud or too soft in the house speakers, and they never competed with Sanborn.

A house PA staff might panic momentarily if an artist invites a guest from the house up onto the stand, but Sanborn’s man seemed unfazed when Grace Kelly joined the band for Hank Crawford’s “The Peeper” and “Let the Good Times Roll.” There was already a second sax mic at the ready. All that was necessary was a slight adjustment of the stand, and when Sanborn did that, there was nary a squeak from the system.

Sanborn’s last two CDs (Here and Gone and Only Everything), both larded with Ray Charles’s repertoire, have been met with mixed reviews, with some folks lauding Sanborn for returning to his roots and some sniffing that the performances are nothing more than imitation Hank Crawford with guest vocals. I’ve found them both a little less crisp than I might like, but after hearing some of the tunes live, I think I know why. It’s not Sanborn’s fault. He can turn on the intensity anywhere, any time. It’s rather that this kind of music is best heard live, and, in more than 20 commercial releases, Sanborn has opted for carefully-controlled studio environments.

In both of these releases, the presence of a big ensemble adds a lot of color, but employing all those other players sacrifices some of the spontaneity that can happen with a small group in a sympathetic club. (For example, the raw, unpolished sound of Ray Charles’s live recording of “What’d I Say,” with the famous give-and-take between Ray and the Raeletts captured in the heat of the moment, has a fire that Ray’s studio recordings miss.) In addition, on “Only Everything,” DeFrancesco’s organ is just one of the many instruments involved, and the organ is a device with a very big ego.

The organ trio is a notoriously difficult thing to record. Most studio dates flatten the Hammond’s sound out in a way that makes it seem lifeless. In an acoustic space, the B-3 blossoms; you get the dynamic shifts with full force, plus that beautiful, low bass resonance from the pedals, and all the schmaltzy drama of the shifts from one register to another, enhanced by the incidental and random ambient sound. Put the instrument behind baffles or in an anechoic environment, and it sounds like the old-fashioned synthesizer that it is. Even adding reverb, as Rudy van Gelder did for Jimmy Smith’s Blue Note dates and Creed Taylor did even more on Smith’s Verve recordings, can’t approximate the real thing, out in the world where it belongs.

Also, the drummer in the organ trio has a role somewhat different from his or her job in other jazz situations. It’s expected that he or she will work as the organist’s third hand, providing rhythmic accents in unison with the other player or picking up instantly on the drama of a sudden decrease in volume. This, too, works best in a live room.

On the other hand, you don’t always want to preserve for posterity the kind of grandstanding that works in live performance. This music wants some give-and-take with an audience, and the players sometimes ratchet up the showbiz in performance to get the crowd going. This is part of the fun of seeing an organ trio live, but that fun is better preserved as a memory than as a CD.

The Scullers show I saw (the second set on February 11) had the balance that was needed—the right acoustics, fine house sound, a superior player at the keyboard, a powerful but sensitive drummer, some familiar razzle-dazzle, some welcome surprises, and the benefits that come from regular performance. As a result, the audience went home mightily satisfied.

About half of the tunes were within Sanborn’s current homage-to-Ray-Charles phase, but the program had other elements as well. The trio opened with Ben Tucker’s “Comin’ Home Baby,” a soul-jazz classic recorded first by Donald Bailey’s band and subsequently covered by Herbie Mann, Mel Tormé, etc., etc. Then, a collection of tunes from the last two CDs—the 6/8 original “Brother Ray,” the abovementioned medley with Grace Kelly, and “Basin Street Blues,” souped up with a “Night Train” shuffle at the end. Michael Jackson’s “The Way You Make Me Feel” segued into one of Sanborn’s groove originals, and the show closed with a crowd-pleasing version of “The Dream.”

I was delighted with Joey DeFrancesco’s good humor throughout. I remember his call-and-response with Sanborn on “Brother Ray,” his quote of “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart” on “The Peeper,” and his smiling rapport with drummer Byron Landham in every solo. It was also nice to hear his occasional use of Coltrane/Tyner harmonies, which distinguish his work from that of other B-3 players and fit well with Sanborn’s harmonic sense. He also surprised me by singing “Let the Good Times Roll” with complete confidence—he wasn’t just phoning in the Joss Stone part from Sanborn’s recording.

Landham, like DeFrancesco, is from Philadelphia, and the two have worked together regularly. He wears serious organ trio service stripes, having played previously with Shirley Scott and with Joey’s father, Papa John DeFrancesco. Hearing a drummer who knows exactly what to do in this setting was a thrill akin to hearing Max Roach or Roy Haynes play classic bebop repertoire.

David Sanborn — his solo tore at the tune with a fierce intensity. It was still candy, but he gave it some of the bitterness of burnt sugar. Photo: Kristophe Diaz

Sanborn’s professional grace on the stand, his easy rapport with the audience, and his absolute control over his instrument guaranteed an almost uninterrupted flow of groove and power. I was momentarily disappointed when he called “The Dream” as a set closer, but I should have known better. This song comes from the book of Interchangeable Modern Ballads that infect adult radio with their moony sentiments and dull harmonies; whenever I hear one, I yearn for just one modern “Prelude to a Kiss” or “Angel Eyes.” Sanborn did the theme as expected, but his solo tore at the tune with a fierce intensity, investing it with something much better than the harmonies deserved. It was still candy, but he gave it some of the bitterness of burnt sugar.

Grace Kelly’s visit to the stand prompted some strong back-and-forth. She knew she had to impress Sanborn’s crowd, and she did just that, showing off the chops that always leave her fellow sax players shaking their heads. Sanborn complimented her by allowing her more solo space on “Let the Good Times Roll” than she actually wanted, waving her to take more choruses after she had finished a nicely-crafted pair. Then, of course, he took over for his own statement and reclaimed command with a solo that was both sparer and more intense.

So it was a fine party. But:

Amidst all the good feeling there was a dark synchronicity. Just before the set began, I learned that Whitney Houston had been found dead in a hotel room in Los Angeles.

I have no philosophical observations about the juxtaposition: 19-year-old Kelly, hugely gifted, ambitiously working her way towards definition of an artistic persona; 48-year-old Houston, daughter to a mistress of soul (Cissy Houston), greatly skilled, deeply flawed, once and never again to be a monumental pop music star; 66-year-old Sanborn, survivor of childhood polio, midlife substance abuse, and a career-interrupting battle with pneumonia, as successful as a non-singing musician can be. All engaged in this weird vocation of making sounds that touch the heart and the brain, sounds that can be new only once, sounds that can be preserved imperfectly at best, sounds that usually survive oblivion only as memories.

At a moment between tunes, Sanborn spontaneously reflected on his status and his career, told his audience how happy he was to be playing at Scullers, what a pleasure it is for him to do what he loves to do and be paid for doing it. He did not need to mention how lucky a successful musician has to be to make a living in The Business, how many things have to go right for him or her to be on that stage, and how easily they can all go wrong.

Sanborn’s trio next plays in New York City at the Blue Note, February 14–19.

Notable recordings in David Sanborn’s career:

Paul Butterfield Blues Band: Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw [1967] /

In My Own Dream [1968] (original Elektra recordings, re-packaged into a twofer by Rhino, 2004)

Taking Off, with Michael Brecker, Randy Brecker, Steve Khan, Don Grolnick, etc.; produced by John Court (Warner, 1975; Sanborn’s first session as a leader)

Voyeur, with Tom Scott, Marcus Miller, Steve Gadd, Patti Austin, etc.;

produced by Michael Colina & Ray Bardani (Warner, 1981)

A Change of Heart, with Michael Brecker, Dr. John, Don Grolnick, Marcus Miller, Steve Gadd, etc.; produced by Miller, Ronnie Foster, Michael Colina, etc. (Warner, 1987; contains “The Dream”)

Another Hand, with Bill Frisell, Marc Ribot, Charlie Haden, Terry Adams, etc.; produced by Hal Willner (Elektra, 1991)

Upfront, with Marcus Miller, Steve Jordan, Eric Clapton, etc.; produced by Miller (Elektra, 1992; contains a surprising version of Ornette Coleman’s “Ramblin’”)

Hearsay, with Marcus Miller, Steve Jordan, Robben Ford, John Purcell, etc.;

produced by Miller (Elektra, 1994)

Inside, with Michael Brecker, Wallace Roney, Bill Frisell, Marcus Miller, etc.; produced by Miller and David Isaac (Elektra, 1999; contains first version of “Brother Ray”)

Timeagain, with Mike Maineri, Russell Malone, Gil Goldstein, Steve Gadd, etc.; produced by Stewart Levine (Verve, 2003; contains Ben Tucker’s “Comin’ Home Baby”)

Here and Gone, with Wallace Roney, Eric Clapton, Joss Stone, Sam Moore, etc.;

large ensemble arrangements by Gil Goldstein; produced by Phil Ramone

(Decca, 2008; contains second version of “Brother Ray,” “Basin Street Blues”)

Only Everything, with Joey DeFrancesco, Steve Gadd, Joss Stone, James Taylor, etc.; large ensemble arrangements by Gil Goldstein; produced by Phil Ramone (Decca, 2010; contains “The Peeper,” “Let the Good Times Roll”)

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.