Film Review: “Adrenaline Rush” Misses Its Mark

The thrilling visuals in this documentary about skydiving get some things right, but the film ends up sensationalizing the sport rather than illuminating it.

Adrenaline Rush -- All Rush and No Science

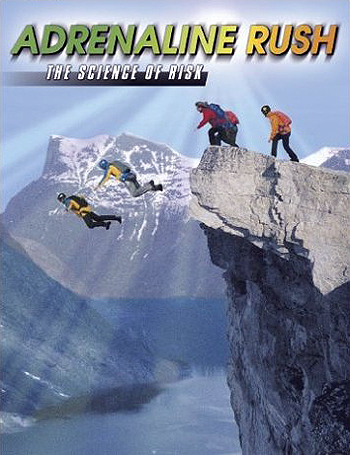

“Adrenaline Rush: The Science of Risk” at the Museum of Science, IMAX, through January 23, 2010.

Reviewed by Kate Vander Wiede

I started skydiving for a few reasons. The first was the incredible high I felt after participating in a birthday tandem jump (where you are attached to an instructor). Paired with support and encouragement from a trusted skydiving friend and a try-anything outlook on life, I dove in to the sport. I took a 7-jump course to learn how to jump by myself: I was taught the safety features of a rig, how to handle a malfunction, the art of packing my own canopy, and the common misconceptions about the sport.

I learned a lot my first few weeks of skydiving. But most of all, I learned how beautiful an experience it is to play around and flip through the sky with friends. The height, which terrified me at first, became normal. My pounding heart, overwhelming on my first jump, soon quieted into a sweet excitement.

With 29 skydives behind me (a very low number in the skydiving world) and my bank account drained, I took a break from the sport I’d grown to love.

This love is what leads me to the Museum of Science’s IMAX dome. The screen is huge, designed to extend further than your peripheral vision in order to immerse you in the visuals of the movie experience. The set-up is tailor made for “Adrenaline Rush: The Science of Risk,” a film that delves into skydiving and BASE-jumping sports and, as the name indicates, the science behind why people take risks.

My involvement in skydiving has given me an understanding of an activity many people don’t know about and has led to friendships with skydivers and BASE jumpers alike. I was particularly interested in analyzing the fairness with which the film portrays this extreme sport —a subjects that the media often misconstrues.

“Adrenaline Rush” is composed of three stories told simultaneously, all of which vary in quality. One tackles the experience of extreme sports. Another follows two individuals who put Leonardo da Vinci’s flight designs to the test. The last tells the story of a boy on his first day of school. So where is the science that the film’s title claims?

There’s not much research to be seen: the 50-minute screening only lends a few minutes to neurobiology and a lackluster risk response experiment that includes the audience. There are no interviews with scientists and no analysis of past research. ‘Scientific’ isn’t the name of this film’s game; science hardly merits a title mention.

Of course, shots of skydivers and BASE jumpers jumping from planes and cliffs create an exciting visual experience for the audience, which is a saving grace of this film. As BASE jumpers hop off rock ledges, the audience flies with them, following their flight from jump to landing. The da Vinci story is interesting enough because we all know who da Vinci was: an artist, dreamer, thinker and inventor whose name evokes ideas of greatness and wonder.

But for all the excitement of the film’s first two subjects, the final first-day-at-school storyline is a glaring misstep. Its placement among such extreme sports seems bizarre, like the filmmaker tried to appeal to parents and children by tacking on a feel-good life lesson we all could relate to. Unfortunately, it doesn’t feel genuine.

The film as a whole suffers from overambitious direction at the service of an undernourished vision. Is this supposed to be a metaphor for the risks we face in real life? A discovery of how our brain works? Profiles on interesting people who do exciting things? A glance into oft-misunderstood aerial sports? In trying to answer so many questions, the film lacks coherence. A movie about science and extreme sports shies away from knowledgeably discussing its ostensible subjects.

What might have saved this film were interviews—with the skydivers, BASE jumpers and scientists. But instead of getting facts and answers straight from the horse’s mouth, “Adrenaline Rush” uses a dramatic voiceover and equally dramatic score to do the heavy lifting.

This lack of context plunks the movie on shaky ground when the risks of extreme sports are discussed. The overpowering voiceover tells the audience “the margin for error in skydiving is nonexistent.” Through my own experiences in the sport, I’ve learned that while skydiving is not risk-free, it has much larger margin of error than widely believed.

While many view skydiving as an out-of-control sport, most of what you do in skydiving IS under your control. You pack your own canopy (though your reserve canopy is packed by a master rigger, an experienced packer who uses a very precise method). You also decide for yourself the conditions you jump in—if the winds are too high, you can sit out. If you are worried about getting hurt when jumping with other people, you can jump by yourself. You also choose when you are ready to jump alone or try tricks—you can take as many coaching lessons as you’d like in order to feel more confident. Skydiving equipment isn’t left to chance, either. Gear is created by well-respected manufacturers who test their designs.

While many view skydiving as an out-of-control sport, most of what you do in skydiving IS under your control. You pack your own canopy (though your reserve canopy is packed by a master rigger, an experienced packer who uses a very precise method). You also decide for yourself the conditions you jump in—if the winds are too high, you can sit out. If you are worried about getting hurt when jumping with other people, you can jump by yourself. You also choose when you are ready to jump alone or try tricks—you can take as many coaching lessons as you’d like in order to feel more confident. Skydiving equipment isn’t left to chance, either. Gear is created by well-respected manufacturers who test their designs.

That being said, accidents do happen that lead to death in skydiving. Just like drivers choosing to hit the highway in less-than-satisfactory weather conditions or individuals not paying close enough attention to the road, many fatalities in skydiving occur from mistakes or bad judgment calls—not blind chance.

The voiceover also declares that even though almost everyone in the BASE-jumping community knows someone who died in a jump, others still continue to do it. Joe S., a skydiver and BASE jumper who has just over 200 skydives and about 50 BASE jumps, answered some questions I had about BASE jumping, but has asked his whole name not be used in this article.

(Through e-mail, Joe told me BASE jumpers suspect that the National Park Service has a list of every known BASE jumper they can find. It is suspected by some that they use this list to deny certain people access to specific national parks with large cliffs popular for jumping, or use it as probable cause to justify detaining a person in their park who they have no other reason to believe has done anything wrong.)

When I restate the film’s comments, Joe tells me that while BASE jumping is inherently more dangerous than skydiving and “if you are active in BASE[jumping] for long enough, chances are that someone you call friend will die doing it,” that that’s not the whole story. Joe shares that these deaths aren’t “always a simple consequence of the fact that BASE jumping is so dangerous, but of the fact that people make poor decisions on how to go about it…. sometimes you make all the right decisions and do all the right things, and it’s just bad luck that can kill you, but a lot of the time there is a long chain of bad decisions leading to a deadly consequence.”

This idea is echoed by many people I know. The risk of skydiving and Base jumping is often self-inflicted. Individuals chooses their own boundaries and determine which risks and situations they are comfortable facing. “Adrenaline Rush” seems to gloss over the idea of individuals having the ability to mitigate risk, choosing to sensationalize a sport instead.

Adrenaline Rush” does get some things right by noting that the first step to skydiving and BASE jumping is gaining clarity of mind in free fall and filming some incredibly visual scenes.

Critic in the Air Having Her Personal Adrenaline Rush

But it gets too many things wrong. In addition to misrepresenting risks and defining BASE incorrectly (jumping from Buildings, Antennaes, Spans and Earth), the film also states that individuals accept the risk of these extreme sports because of their faith in the physics of their canopy. This is similar to stating that airline passengers accept the risk of flying home for the holidays because they have faith in aerodynamics. Physics and aerodynamics aren’t subjects that depend on faith—they exist through laws and are applied through equations and design.

Most importantly, the film seems to leave out a very important part of why people participate in extreme sports, besides the high they might get from it.

Joe shares his reasoning eloquently. “To me, it is literally the feeling of having superpowers and of complete disconnection from the earth, and the security that most people need to feel 100% of the time. There is not any other time that I can think of that truly puts you in the moment of what you are doing more than the second you have committed to a jump and your feet have just left the edge. That moment of commitment is why I keep coming back. At this moment there is no other care in the world except the jump itself and for a few brief seconds it feels as though you are the only person on the earth.”

“Adrenaline Rush” misses these inspiring aspects of the sport, so while the visuals in film make it compelling it doesn’t lift your spirit or mind off the ground.