Visual Arts: Where’s Theo? Is that Theo van Gogh in the picture?

Nothing would please me more than to believe the announcement made last week by the Van Gogh Museum, saying that one of the paintings in the museum that has always been called a self-portrait by Vincent van Gogh is in fact a portrait of his brother Theo.

By Gary Schwartz

Theo’s dedication to Vincent is one of the most inspiring stories I know. So great was his belief in Vincent van Gogh’s art and career and so overriding was his love for his difficult brother that during long years when no work by Vincent was being sold, he spent about one-third of his income to keep Vincent alive and at work. For two years, Vincent lived in Theo’s flat in Paris. It has always bothered students of van Gogh that he seems not to have painted a portrait of his near-saintly brother.

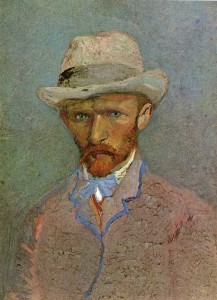

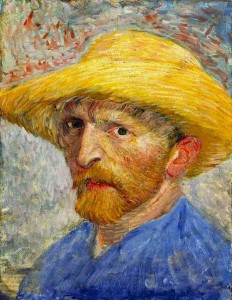

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait now said by the Van Gogh Museum to portray Vincent’s brother Theo (F 294)

The occasion for the announcement by the museum that it had identified Theo in the sitter of a painting heretofore called a self-portrait is a happy one. Twelve years after the appearance in 1999 of vol. 1 of the collection catalogue of the paintings by van Gogh in the Van Gogh Museum and only three years after its announced publication date of 2008, vol. 2 has appeared. (As of June 28, 2011, the museum website continues to promise vol. 2 in 2008. Forgive me for nitpicking, but columnists are there to keep institutions honest, no?) Vol. 1 dealt with the early paintings made in the Netherlands, vol. 2 deals with those from the Antwerp and Paris periods.

To mark the event, a small, delectable exhibition has been mounted, Van Gogh in Antwerp and Paris: new insights. It is an outstanding exemplar of the kind of informative, art museum exhibition that provides the visitor with the background and context beneath and behind the work itself. The paintings are grouped into 15 ad hoc categories, beginning with

How was a painting begun?

What is this painted on?

What colour is this?

Where is this?

Each question is answered with a small demonstration, including not only one or more paintings by van Gogh and an explanatory text in Dutch and English but also auxiliary materials—X-rays or infrared reflectograms, photos of the back of the canvas or panel, painter’s aids such as a perspective frame. On the X-ray of a landscape painting, for example, the threads of a perspective frame like the one in the exhibition showed up clearly, bringing the viewer close to the craft mechanics employed by van Gogh. My favorite attribute was a box of wool balls in the section “What colour is this?” The artist kept an assortment of wool balls of various colors in order to see beforehand the effect of different color combinations. The object in the show is the actual lacquer box that belonged to van Gogh.

The museum unwisely chose to publicize the exhibition with a section that, unlike the balls of wool and infrareds, is highly speculative. Called “Who is this?,” the panel shows the two small portraits illustrated above, supplemented by a number of photographs of the brothers Vincent (1853–90) and Theo van Gogh (1857–91). Comparing features like hair color and—emphatically—the shape of the ears, the museum comes to the resounding conclusion, which made all the Dutch media, that the former Self-portrait in a straw hat is a portrait of Theo van Gogh in a straw hat.

This question has a history that is reconstructed in some detail, but in my opinion inadequately, in the collection catalog. In 1943, a note in the catalog tells us, the Swedish art historian Carl Nordenfalk (1907–92) recorded in a letter the opinion on the issue of Theo’s son Vincent Willem van Gogh (1890–1978; in the van Gogh world always called The Engineer, after his profession, which in Dutch is a title: Ir. [Ingenieur]). When Nordenfalk asked him whether the two small portraits might depict his father, who died six days before Vincent Willem’s first birthday, the Engineer denied it, “adding that no one in the family had ever suggested they were.”

At this point a certain discrepancy appears in the catalogue. The note continues: “When De La Faille made the same suggestion [as had Nordenfalk] years later, Vincent Willem vehemently denied it.” De La Faille was the pioneer cataloger of the work of van Gogh, Jacob Baart de la Faille (1886–1959). In the text of the catalogue, however, De La Faille is said to have posited a significantly different suggestion than Nordenfalk’s:

Both paintings were traditionally regarded as self-portraits. But in 1958, De La Faille raised doubts about cat. 122 [Self-portrait in felt hat]. Working on the premise that it would have been very odd if Vincent had never painted his brother during the two years he lived with him in Paris, he suggested that this was a portrait of Theo. There was a close resemblance between the brothers, as Jo van Gogh-Bonger noted in 1914, the main difference being that her husband was “more delicately built and his features were more refined, but he had the same reddish fair complexion.” Vincent Willem van Gogh, Theo’s son, dismissed De La Faille’s theory, and the question of whether one of Van Gogh’s supposed, painted self-portraits is in fact a portrait of his brother has never been posed since.

The difference between the versions of events in the note and in the text is significant because Nordenfalk thought the two paintings showed the same person, and De La Faille that they were different persons. The Van Gogh Museum has now shifted from the same-person identification to the two-different-persons one but has reversed the identity of the two sitters. Whereas De La Faille thought that the man in the felt hat was Theo, the museum now calls him Vincent and the sitter in the straw hat Theo.

This part of the discussion takes place on the slippery slope of non-eyewitness identification. I must say that I found the visual demonstration and the analysis of ear shapes unconvincing. Vincent’s other self-portraits show such a wide variety of looks, shapes and colors that I would hesitate pronouncing a firm verdict concerning these two images.

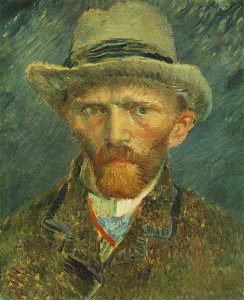

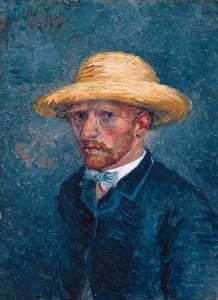

Here are two other self-portraits from the Paris period in which Vincent poses with the same kind of hats as in the pair in the Van Gogh Museum. The differences in beard color and the shape of the ear between the one and the other are no less pronounced than in the pair now in question.

The next stage in the story raises a more fundamental problem. In 1960 the Dutch art historian and art critic Bram Hammacher (1897–2002), a historical personage in his own right, wrote an introduction to a book on the self-portraits of van Gogh brought out by the German publisher Reclam. Coming two years after De La Faille’s attempt to find an image of Theo among the self-portraits, Hammacher could not evade the issue. Here is the way the new catalog reports on this key moment:

When De La Faille made the same suggestion [as Nordenfalk’s] years later, Vincent Willem vehemently denied it. ‘Absolutely out of the question! My mother said it was Vincent’ (‘Geen sprake van! Mijn moeder zeide dat het Vincent was’), as he noted in his copy of De La Faille’s oeuvre catalogue of 1939 (BVG 447a), and it was because of this that A. M. Hammacher rejected De la Faille’s suggestion (Hammacher 1960, pp. 9, 10). However, it is still unclear whether Jo knew the two portraits well or studied them closely. Neither painting is mentioned in her letters or notes, and they were never selected for an exhibition while she was alive.

This is however not at all the reason that Hammacher himself gives for rejecting De La Faille’s proposal.

De La Faille saw in [Self-portrait in a felt hat] a painting that van Gogh apparently made of Theo. We would love to know of a portrait of Theo by Vincent, but aside from a mention in a Bernheim-Jeune catalogue of 1901, none has ever been identified . . . . The first one who would have had to know of the existence of such a painting was Theo’s wife. After all, she owned this portrait from Paris. Her son, Vincent van Gogh Junior, assured me emphatically that his mother had always regretted that there was no portrait of Theo by Vincent.

After all, indeed. Jo van Gogh-Bonger (186–1925), Theo’s widow, owned both of the paintings from Theo’s death until her own. During that quarter-century, she devoted herself, as had Theo, to the care of Vincent’s oeuvre and husbanding his posterity and market. To say that it is “unclear whether Jo knew the two portraits well or studied them closely”—less closely than the present curators of the museum, that is—strikes me as a rhetorical trick to avoid dealing seriously with Jo’s reported opinion. Worse is that the museum puts words into Hammacher’s mouth rather than citing what he actually wrote. He was not talking about the facial features of this sitter or that in a particular painting, as the museum suggests, but about a categorical denial by Jo—albeit hearsay two steps removed from the source—that Vincent ever painted a portrait of Theo.

“Her son, Vincent van Gogh Junior, assured me emphatically that his mother had always regretted that there was no portrait of Theo by Vincent.” As long as this powerful quotation is missing from what the Van Gogh Museum tells us about the new identification, along with a convincing refutation, I cannot accept their theory. There is always a chance that the museum is right and Hammacher, Vincent Willem, and Jo were wrong. But as things stand, it’s the museum’s word against that of Jo van Gogh. I’m with Jo, especially given the equally unsettling fact that Vincent is not known ever to have drawn or painted a portrait of her or the baby Vincent either.

The quotation above of Hammacher’s remarks are my own translation from the German, taken from Fritz Erpel, Die Selbstbildnisse Vincent van Goghs, Berlin (Henschelverlag) 1970, p. 70, nr. 9.

“De la Faille sah in Nr. 196 ein Bild, das van Gogh angeblich von Theo gemacht haben soll. Wir würden gern ein Porträt Theos von Vincent kennen, aber außer einer Erwähnung im Katalog von Bernheim-Jeune 1901 ist es durch niemanden jemals identifiziert worden (s. Les Cahiers de van Gogh Nr. 4, Genève 1958). Die erste, die vom Vorhandensein eines solchen Bildes hätte wissen müssen, wäre Theos Frau gewesen. Sie besaß übrigens dies Porträt aus Paris. Ihr Sohn, Vincent van Gogh junior, hat mir ausdrücklich versichert daß seine Mutter es immer bedauert habe, daß es kein von Vincent gemaltes Bildnis Theo gegeben habe.”

Erpel adds the following caveat: “Auch Hammachers Argumentation bleibt ohne schlüssige Beweiskraft; vgl. nämlich das Zeugnis Johanna van Gogh-Bongers S. 45 dieses Bandes.” (Hammacher’s argument as well is inconclusive; compare the testimony of Johanna van Gogh-Bonger on p. 45 of this volume.) On p. 45 there are two quotations from Jo about Theo and Vincent, but neither as I see it weakens the statement attributed to her by Hammacher.

For an article on the budget cuts in the arts in the Netherlands that I wrote for The Art Newspaper, see the summer issue, shortly to appear.

© Gary Schwartz 2011. Published on the Schwartzlist on June 28, 2011.

Gary Schwartz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. In 1965 he came to the Netherlands with a graduate fellowship in art history and stayed. He has been active as a translator, editor, and publisher; teacher, lecturer, and writer; and as the founder of CODART, an international network organization for curators of Dutch and Flemish art.

As an art historian, he is best known for his books on Rembrandt: Rembrandt: all the etchings in true size (1977), Rembrandt, his life, his paintings: a new biography (1984) and The Rembrandt Book (2006). His Internet column, now called the Schwartzlist, appeared every other week from September 1996 to April 2007 and has been appearing since then irregularly. His most recent book on Rembrandt is one of the six titles nominated for the Banister Fletcher Award for the most deserving book on art or architecture of that year.

In November 2009, Schwartz was awarded the coveted tri-annual Prize for the Humanities by the Prince Bernhard Cultural Foundation of Amsterdam.

Responses always welcome at Gary.Schwartz@xs4all.nl