Opera Album Review: Two Composers — One Vivid French Baroque Opera, Based on Euripides

By Ralph P. Locke

Two-plus hours of delight for anybody interested in Baroque opera, or willing to try it.

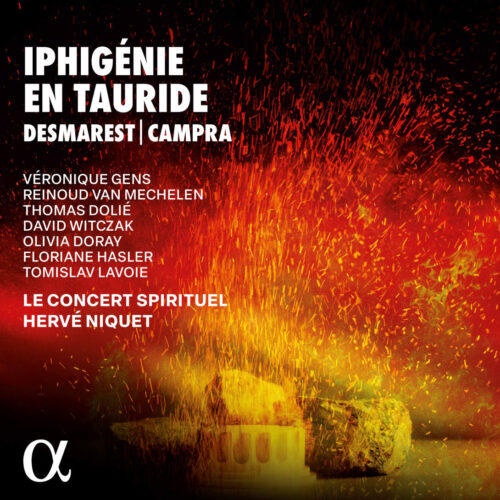

Henry Desmarest and André Campra: Iphigénie en Tauride

Véronique Gens (Iphigénie), Olivia Doray (Electre), Floriane Hasler (Diane), Reinoud van Mechelen (Pylade), Thomas Dolié (Oreste), David Witczak (Thoas)

Le Concert Spirituel/ Hervé Niquet

Alpha 1106 [2 CDs] 136 minutes

93 tracks in 136 minutes. That works out to a minute and a half per track. Yes, we have here another French Baroque opera full of melody, dancelike verve, and sudden drama, always shifting mood before the listener can get remotely bored. No lengthy da capo arias. And, as always, no secco (continuo-accompanied) recitatives: instead, brief arioso-like exchanges over an orchestral accompaniment that can be as interesting and forward-pushing as it is in the arias and duets. Oh, and lots of numbers for chorus and orchestra or for orchestra alone; many of these are dances (confusingly called “airs”). We also get a “March of the Scythians” and a “March of the Sacrificial Priests.”

93 tracks in 136 minutes. That works out to a minute and a half per track. Yes, we have here another French Baroque opera full of melody, dancelike verve, and sudden drama, always shifting mood before the listener can get remotely bored. No lengthy da capo arias. And, as always, no secco (continuo-accompanied) recitatives: instead, brief arioso-like exchanges over an orchestral accompaniment that can be as interesting and forward-pushing as it is in the arias and duets. Oh, and lots of numbers for chorus and orchestra or for orchestra alone; many of these are dances (confusingly called “airs”). We also get a “March of the Scythians” and a “March of the Sacrificial Priests.”

In short, two-plus hours of delight for anybody at all attuned to the pleasures of Baroque music.

The release has the added excitement of being a world-premiere recording of a work begun by Henry Desmarest (the renowned director of the Paris Opéra a generation or two after Lully) and completed by André Campra, an equally renowned composer of operas and ballets. Campra’s tunefulness is sometimes attributed to the fact that he came from Provence, with its rich tradition of pipe-playing accompanied by drum—the two instruments adroitly managed by one and the same performer.

And Desmarest? Well, his best-known work, Circé, impressed me greatly for its mix of mellifluousness and drama in two recent recordings that came out almost simultaneously: one by the Boston Early Music Festival, with Lucile Richardot in the title role, the other by a group called Les Caractères featuring the star soprano heard who is also heard here, Véronique Gens.

The work, as we learn from the informative essay by musicologist Benoît Dratwicki, was first performed in 1704, and kept getting revived as late as 1762, and was even published, with clear indications of which of the two composers had penned which numbers.

A lively movie could be made about the work’s composition: Campra finished it because Desmarest had been forced into exile for having had an affair with a young woman and marrying her without her father’s permission. Desmarest was even condemned to death in absentia. He lived and worked in Spain for some years, and thereafter in Lorraine, which was not yet part of France. He was eventually pardoned in 1720 by the French regent, but his application for a position in court was denied, so he chose to remain in Lorraine until his death in 1741.

The opera tells basically the same story that the world has known for two millennia from Euripides’s play of the same name. The story would be told again in Gluck’s rightly acclaimed opera of 1779. So if you know the play or the Gluck opera, you won’t have much trouble keeping track of what is going on. (The Gluck exists in many notable recordings, including an early one, from the monophonic era, conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini and more recent ones conducted by John Eliot Gardiner, Riccardo Muti, Martin Pearlman, and Ivor Bolton. Each of these features some of the greatest singers of the respective era.) The booklet includes a helpful synopsis plus the libretto, and everything is in both French and good English.

The ever-splendid soprano Véronique Gens. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Iphigenia (I’ll use the familiar English names; the French ones are in the header) has been whisked away to a distant land by Diana to prevent her father Agamemnon from sacrificing her in order to placate the gods (because he promised he would do so if they would allow the winds to blow, so he could send his soldiers on ships to fight against the Trojans). The main drama involves the surprise arrival of Orestes and his childhood friend Pylades, who save Iphigenia from the menacing Taurian leader Thoas and various sacrificial priests. Unlike in the original Euripides drama and in Gluck’s opera, Electra—the sister of Iphigenia and Orestes—is present as well, and Thoas becomes obsessed with winning (or commanding) her love.

The music is, by turns, touching, enchanting, delightful. Act 4, for example, begins with a basso-ostinato aria that resembles in this respect, and is no less engaging than, “When I am laid in earth,” from Purcell’s remarkable, decades-earlier Dido and Aeneas. Campra completed some scenes that Desmarest had sketched out (including two encounters between Orestes and Electra), and he composed the overture, the various dance- and chorus-filled divertissements, and the prologue, in which the people of Delos celebrate the birthday of Diana (and her brother Apollo) until Diana announces that she is leaving to help save Orestes, who is at risk of being put to death when he arrives in the land of the Taurians, unaware that he will end up meeting Iphigenia there.

The instrumental and choral ensemble led by Hervé Niquet is ever on its collective toes. The continuo is richly outfitted: harpsichord, two theorbos, two “basses de violon,” and two violas da gamba. In accordance with the latest research by Versailles Baroque-Music Center, the continuo group goes silent during the dances, adding further to the variety of sonorities and textures across the work. The sound is clear and well balanced. The recording was made during a concert in the hall of the Conservatory at Puteaux, plus, it seems, some sessions without an audience.

Conductor Hervé Niquet. Photo: Henri Buffetaut

The singers here are mostly assigned only one role apiece (except for some who each take several minor roles). The best are the women listed above, led by the ever-splendid Véronique Gens (see my praise of her in works by Rameau and Halévy) and the tenor Reinoud van Mechelen, whom I have praised here before (in works by Charpentier and Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre).

The three baritones or bass-baritones (two listed above, plus Tomislav Lavoie) are weak in their lower registers, a common issue among low male voices in early music today. In addition, David Witczak often does not hit pitches firmly, as was also the case in two other recordings that I reviewed here in which he had prominent roles. But all the singers pronounce the text clearly (in modern French pronunciation, I’m pleased to say, which makes for easier comprehension) and seem engaged in the action.

In short, a major offering for anybody interested in Baroque opera, or willing to try it. For the uninitiated, works that are more frequently performed than this one might offer a preferable first experience: for example, Lully’s Armide or Rameau’s Les Indes galantes (which comprises four short operas, preceded by a meaty prologue involving the gods in heaven).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and Senior Editor of the Eastman Studies in Music book series (University of Rochester Press), which has published over 200 titles over the past thirty years. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and Classical Voice North America (the journal of the Music Critics Association of North America). His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here, lightly revised, by kind permission.

Tagged: André Campra, Henry Desmarest, Hervé Niquet, Iphigénie en Tauride, Le Concert Spirituel