April Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Classical Music

James Freeman, best known as the founder and longtime conductor of the Philadelphia-based Orchestra 2001, is also a remarkable pianist (and an accomplished double-bass player and Swarthmore professor, now emeritus).

James Freeman, best known as the founder and longtime conductor of the Philadelphia-based Orchestra 2001, is also a remarkable pianist (and an accomplished double-bass player and Swarthmore professor, now emeritus).

I have already praised here a CD of three pieces that he and his brother, the late Robert S. Freeman, commissioned from notable American composers Andrea Clearfield, Kevin Puts, and Gunther Schuller. The brothers played, with impressive command, the Schuller work: a highly demanding sonata for two pianos.

Here we have the first of two CD releases of solo-piano recordings that James Freeman made in 2004 and 2007 (but never released) in the clear, well-balanced acoustics of Swarthmore’s Lang Concert Hall. The repertory on this first disc is utterly standard: seven Chopin mazurkas, Robert Schumann’s Kinderszenen, a capriccio and four intermezzi by Brahms, and four highly contrasting pieces from Debussy’s Préludes, book 1.

But the performances are not “standard” at all: they sound quasi-improvised, as if Freeman were composing each piece in front of us. I felt invited into the music, instead of being treated as somebody who needed to be persuaded or wowed.

The freedom of tempo is never excessive. Lovers of piano music will recall some recordings, e.g., by Glenn Gould (of Mozart) or Philip Corner (of Satie), in which the tempos are bizarrely slow. Here, instead, the listener is treated as someone who appreciates true sentiment and enjoys noticing slight pushes and pulls in a tempo that respond to turns in the harmony or to variations in the curve of a melody.

Freeman plays with a solid core of tone, and with exquisite applications of the sustaining pedal. This is one of the most purely enjoyable piano recordings I have heard in a long time. (Test-drive any track here.) I look forward to its successor, to be released in mid-April and featuring twentieth-century pieces.

— Ralph P. Locke

Classical Music Concert

Isidore String Quartet. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Named after one of the players in the Juilliard Quartet, violinist Isidore Cohen, these four musicians (violinists Adrian Steele and Phoenix Avalon, violist Devin Moore, and cellist Joshua McClendon) banded together to become the Isidore Quartet just before the outbreak of COVID. The group’s noniker also acknowledges a shared affection for a certain libation — legend has it a Greek monk named Isidore concocted the first vodka recipe for the Grand Duchy of Moscow!

I heard them in a gorgeous new hall at the Groton Hill Music Center under the auspices of Boston’s Celebrity Series, and it was an a concert that brought tears, and tears of joy, to those lucky enough be in the audience.

They started off with a quartet composed by “Papa Haydn” (a.k.a.The Father of the String Quartet), one among his famous Opus 20 set of string quartets. The Isidores reminded me, with their continual elegance, of how much this reviewer had missed by waiting until late in life to discover Haydn’s 68 string quartets. This was a stunning concert opener.

The next piece, String Quartet #2, “ The Awakening,” by the multi-talented composer and jazz pianist Billy Childs, was gripping from beginning to end. According to the program notes, the frenetic first movement dramatizes Billy getting a call that his wife is in the hospital with a pulmonary embolism. Gripped with fear, he rushes off to see her, disoriented: there are sounds of the hospital machines and chaos in the background. Luckily, his wife recovers and, in the third movement, Childs and his wife reconcile and fall, again, in love after all of the terrifying tumult. (Phoenix Avalon was terrific in the first violin chair, as was Adrian Steele as first violin in the Haydn and Beethoven).

Beethoven wrote Opus 132 String Quartet #15 after he recovered from a life-threatening intestinal disorder. Delight follows recovery here, an arc that uncannily mirrors Child’s narrative. Oddly, it seemed as if they belong together. Its ravishing third movement, “Holy Song of Thanksgiving of a convalescent to the Deity in the Lydian Mode,” is among Beethoven’s most beloved string quartet movements. Here it was played to perfection.

— Susan Miron

Film

A scene from Stanley Kubrick’s first feature, Fear and Desire.

Fear and Desire is written by Howard Sackler and directed by Stanley Kubrick. It’s available digitally on iTunes, Vudu, and Google Play.

What generally happens when you seek out the first film made by a long-established director? Sometimes you get a real treat. Oftentimes you’re disappointed. On occasion, the result falls in between. Such is the case with Stanley Kubrick’s (barely) feature-length 1953 debut Fear and Desire, now available on Blu-ray and 4K UHD formats (Kino Lorber).

Differing accounts from film historians have ranged about why the then-24-year-old Kubrick pulled the film from theaters soon after it was released — either because he wasn’t satisfied with it or audience response was negative. An uncontested fact is that it was originally 70 minutes long, but was cut down to 62 minutes (both versions appear on the new release, along with three early Kubrick shorts, the best of which is the entertaining boxing doc Day of the Fight).

Fear and Desire plays out as an existential drama: it is a war film in which the locale and the warring countries aren’t named (my bet is Europe with Americans going up against Germans).

It opens just after a plane crash has left a small platoon of soldiers stranded – and lost – approximately six miles behind enemy lines. Or so they believe. Using a combination of narration, straightforward dialogue, and various inner monologues (some of it philosophical babble), the Sackler script highlights the angst among the men as they attempt to survive, both physically and emotionally.

There’s not much plot but a few instances of overacting (mostly from the unhinged soldier Sidney, played by Paul Mazursky in his screen debut). The film supplies a valuable opportunity to see Kubrick’s cinematic baby steps – he also photographed and edited. The B&W images are crisp, compositions are exceptional, and an intermittent use of silences effectively adds to the tension. So, is the film worth seeing, or is it just for Kubrick completists? Yes, it is, and no it’s not. Anyway, aren’t you curious?

— Ed Symkus

Jazz

A portrait of FYEAR. Photo: Frank Schemmann

The first sound heard on FYEAR (Constellation Records) is a violin sawing its way through a vicious sonic squawl. Poet Tawhida Tanya Emerson, one of the band’s two vocalists, soon begins to shout. FYEAR’s noisiest moments are inspired — by free jazz — to express a growing dread of the future: “how can I see when the narrative ticks counter clock?” Even the quiet passages that run through the album, such as the start of “Pt. IV: Degrees,” feel like the exhaustion that follows an anxiety attack. The group sports an unusual lineup: spoken word contributions from Emerson and Kate Kellough along with pedal steel guitar, two violins, and two drums.

FYEAR’s vocals are their least successful element. They are obviously inspired by Moor Mother’s noise-jazz-rap poetry, but neither Kellough nor Emerson can match her commanding presence. What’s more, the lyrics smash hammer home didactic points. (FYEAR seems to feel that our times have become too desperate for subtlety.) Still, doomer sentiments are placed in a context of constantly shifting dynamics and moods that make them work musically. The effects of climate change lie heavily on FYEAR’s mind. Imitating a weather report about new extremes of cold and heat, “Pt. II: Mercury Looms” blurts out its dark forecast as plainly as possible as it speeds up to its frantic ending. Kellough and Emerson step over each other’s words to conjure up the angst of watching as “ice expands in the heat…water freezes in midsummer.”

Intended as a single 45-minute composition, FYEAR is broken up into seven parts for streaming. The music may alternate between soft and loud passages, but it never veers far from its spirit of dystopian panic. “Pt. VII: Pure Pursuit” weeps for the uncertainty of human existence. To use cultural critic and theorist Mark Fisher’s pungent phrase, their music describes the psychological damage caused by “the slow cancelation of the future”.

— Steve Erickson

Popular Music

Evan Lewis and Tom McGreevy of Ducks Ltd. Photo: Colin Medley

One listen to Harm’s Way, Ducks Ltd.’s latest release (Carpark, February 9, or their 2021 debut, Modern Fiction) and the listener will hardly be flummoxed upon learning that lead guitarist Evan Lewis believes that “The Feelies [click for my Arts Fuse interview] are the greatest American jangle pop band” and that he and bandmate Tom McGreevy are “big fans of fast tempos and clean guitars, and The Feelies do this better than anyone else.”

Similarly, it will come as no shock that singer and songwriter McGreevy said, in contrasting their approach to Harm’s Way with previous efforts (including their 2021 EP, Get Bleak), “now, instead of asking ‘what would Orange Juice do?’, we’d ask, ‘what would we do?’”

With nine tracks that run for slightly less than 28 minutes, Harm’s Way is one track and two minutes shorter than its predecessor. As underwhelming (if that’s a word) as that might sound, the nonstop quality of the material is anything but.

The singles “Train Full of Gasoline,” “Hallowed Out,” and “The Main Thing” – three of the records’s first four tracks – alone constitute a runneth-over cup, and there’s plenty more where that came from.

Picking favorites is a fool’s errand. Each track is joyously and spine-tinglingly reminiscent of the Murderer’s Row of English, Scottish, Australian, Kiwi, and American jangle pop artists whom the dyad cites as influences, although “Heavy Bag” closes the curtain on a folky note unheard elsewhere on the album.

Like their Carpark Records lablemates The Beths (click here for my Arts Fuse coverage), Ducks Ltd. became one of my new favorite bands at first listen. Sadly, their current tour with Ratboys isn’t stopping in Boston because it’s not a big college town. So if you can’t make it to Portland, ME, Burlington, VT, or Hamden, CT, then use the time and money that you would have spent to purchase their entire catalog.

— Blake Maddux

Books

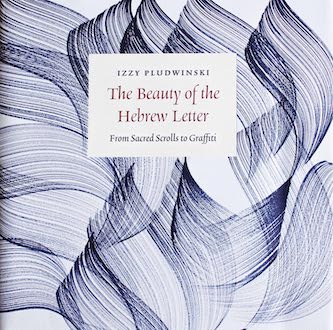

The gorgeously produced The Beauty of the Hebrew Letter: From Sacred Scrolls to Graffiti (Brandeis University Press, 240 pages) is a spellbinder. In it, Jerusalem-based scribe Izzy Pludwinski illustrates the transformation of Hebrew letters into objects d’art, untethered from their past use as the building blocks of sacred texts. Filled with over 200 stunning illustrations, the volume follows the letters through their various appearances — on the surfaces of stone, parchment, and paper. The time frame is expansive: from Biblical times to our own, charting the alphabet’s use in historical manuscripts and innovative writing techniques to their use in street and fine art.

The gorgeously produced The Beauty of the Hebrew Letter: From Sacred Scrolls to Graffiti (Brandeis University Press, 240 pages) is a spellbinder. In it, Jerusalem-based scribe Izzy Pludwinski illustrates the transformation of Hebrew letters into objects d’art, untethered from their past use as the building blocks of sacred texts. Filled with over 200 stunning illustrations, the volume follows the letters through their various appearances — on the surfaces of stone, parchment, and paper. The time frame is expansive: from Biblical times to our own, charting the alphabet’s use in historical manuscripts and innovative writing techniques to their use in street and fine art.

The Beauty of the Hebrew Letter is by no means the only study that explores the significance of the Hebrew alphabet — especially its mystical meaning. One of my favorite volumes is Rabbi Lawrence Kushner’s The Book of Letters, A Mystical Jewish Alphabet. He gathers together stories inspired by the letters, which “are themselves holy… sources of wisdom, meditation and fantasy… vessels carrying the light of the Divine.” Another fave is Ben Shahn’s The Alphabet of Creation, An Ancient Legend from the Zohar, which features the artist’s memorable drawings.

Pludwindki’s book is a radically different from those I just mentioned. He closely examines three millennia of Hebrew calligraphy, divorcing the letters from their accepted spiritual or numerical meanings, emphasizing the aesthetic possibilities inherent within the Hebrew alphabet. The author is a professional calligrapher, and he goes into detail about how Hebrew writing has been created through the ages: it has been created by reed and quill, chiseled into stone, cleaved from wood, carved into leather.

Contemporary calligraphy artists, who often have little or no connection with traditional approaches to the craft, have encouraged the creation of fresh, innovative versions of the Hebrew alphabet. I was amazed by the visuals in the latter part of the book, phantasmagoric illustrations, via street and fine art, whose dancing shapes began, somehow, as letters we’ve known our entire lives. The aesthetic possibilities of how we can imagine these ancient letters looks to be boundless.

— Susan Miron

Grady Hendrix, known for his horror/comedy books, terrifies fans with a story about grief, family loss, and secrets in his latest novel, How to Sell a Haunted House (Penguin Random House, 432 pages).

Grady Hendrix, known for his horror/comedy books, terrifies fans with a story about grief, family loss, and secrets in his latest novel, How to Sell a Haunted House (Penguin Random House, 432 pages).

Louise is a single mom who returns to her hometown after her parents’ sudden death. She must reconnect with her brother, Mark, years after they’ve grown apart. They have intense arguments about funeral arrangements and their inheritance, including what to do with their mom’s creepy doll and puppet collection. Especially her favorite one, the terrifying Pupkin. Old memories come to the surface, including chilling events involving Pupkin from Louise’s childhood that she has worked hard to forget.

The novel stands out from the usual killer puppet tale because every element in the narrative is grounded in the trauma someone feels after tragically losing a family member. This notion of irreparable loss is related to Pupkin’s origin story — it is why he keeps coming back, even after the doll is tossed in the trash, burned, and even buried. The author craftily creates a story in which the characters and reader initially fear Pupkin but end up feeling sorry for the glove puppet.

Be warned — this is one of Hendrix’s scariest novels, even though the author supplies his customary touches of comedy to balance out the often somber storyline. The addition of some graphically gory episodes is a bold choice, and they are capped by a distinctive — and visually haunting — climax. The ultimate battle is treated with a gaudy grandeur that might be too campy for some, but it works well with Hendrix’s intent to evoke a sense of the horror of yesteryear, cira the ’80s.

— Ana Peres

“Beliefs are such a comfort to people until you ask them to explain,” an aspiring journalist notes after an inconclusive interview with a reclusive musician in one of the stories in Ghost Pains. Yet she cannot bring herself to ask the musician to explain his cryptic response. It feels safer to tiptoe around trap doors “that lead you deep into the mountains of your own mind.” Now that the history we’d been told was dead has returned on steroids, how much clarity do we really want? How much can we bear? Jessi Jezewska Stevens’ bracing collection of stories Ghost Pains (And Other Stories, 192 pages) is a tonic for the moral and intellectual muddles of the information age. The belief systems slipping from her characters’ grasps have little comfort and no explanations to offer. Still, these characters are good company and the narrators’ wry asides and acerbic commentaries make their disorientation unexpectedly clarifying.

“Beliefs are such a comfort to people until you ask them to explain,” an aspiring journalist notes after an inconclusive interview with a reclusive musician in one of the stories in Ghost Pains. Yet she cannot bring herself to ask the musician to explain his cryptic response. It feels safer to tiptoe around trap doors “that lead you deep into the mountains of your own mind.” Now that the history we’d been told was dead has returned on steroids, how much clarity do we really want? How much can we bear? Jessi Jezewska Stevens’ bracing collection of stories Ghost Pains (And Other Stories, 192 pages) is a tonic for the moral and intellectual muddles of the information age. The belief systems slipping from her characters’ grasps have little comfort and no explanations to offer. Still, these characters are good company and the narrators’ wry asides and acerbic commentaries make their disorientation unexpectedly clarifying.

The sense of self is also subject to serious slippage here. Stevens’ characters are bewildered and in-between, many of them suffering from profound mental — even existential — jetlag. Having grown up with, or simply become used to, one set of expectations and way of understanding the world, they slowly, then suddenly, find themselves in entirely new circumstances. That is, their circumstances haven’t changed, but have become all but unrecognizable. In one story a woman is so haunted by the frequent comparison between the Weimar republic and our current age that she begins to embody it. In another, a rewriting of Rumpelstiltskin for the cryptocurrency age, an insurance claims reviewer locked out of his multi-million BITCOIN account promises a woodland imp his next girlfriend in exchange for the lost password. Intimacy, not surprisingly, is complicated in this collection. In “Siberia”, two former lovers can only recapture their lost closeness over the phone in lockdown. “Honeymoon” opens with a sigh from a recent bride who longs for “those early months of courtship, when everything was still uncertain … The thrill of the ask. The space.”

For all the heady thrill of her prose, Stevens is a sharp observer of the physical world. Trees bending over a road are “knighted by snow;” a toppled basil plant is surrounded by “soil scattered like black blood;” a laptop thrown from an upstairs window languishes like “carrion…on the cobblestones, wires rising like new sprouts.” And she is an even sharper observer of human foibles and absurdity and the lengths to which we go to avoid explaining them. Ghost Pains is a haunted and enchanting look at manners of anxiety.

(For disclosure, New York Review Books commissioned Jessi Jezewska Stevens to write an introduction to my translation of Ernst Jünger’s On the Marble Cliffs.)

— Tess Lewis

Incisively impish, Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz (1904-1969) is a grievously neglected modernist master. Admirer Charles Simic observed that for Gombrowicz “in contrast to the philosopher, the moralist, the priest, the artist is engaged in endless play, a form of play, he adds, that has a right to exist only in so far as it opens our eye to reality – some new, sometimes shocking reality, which makes art palpable. If that meant poking fun at some earnest behavior or deeply held belief — so be it.” His novel The Possessed (Grove Atlantic, Black Cat imprint, 416 pages) lampoons stale literary conventions, but it’s debatable if the narrative offers a refreshed vision of reality. Critics have long dismissed the book as a potboiler, written for money and published in the mid ’30s under a pseudonym. Still, some see the narrative’s sado-masochistic short-circuiting of a hot-to-trot young couple — with geriatric spirits hovering about — as an anticipation of 1960’s superior Pornografia.

Incisively impish, Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz (1904-1969) is a grievously neglected modernist master. Admirer Charles Simic observed that for Gombrowicz “in contrast to the philosopher, the moralist, the priest, the artist is engaged in endless play, a form of play, he adds, that has a right to exist only in so far as it opens our eye to reality – some new, sometimes shocking reality, which makes art palpable. If that meant poking fun at some earnest behavior or deeply held belief — so be it.” His novel The Possessed (Grove Atlantic, Black Cat imprint, 416 pages) lampoons stale literary conventions, but it’s debatable if the narrative offers a refreshed vision of reality. Critics have long dismissed the book as a potboiler, written for money and published in the mid ’30s under a pseudonym. Still, some see the narrative’s sado-masochistic short-circuiting of a hot-to-trot young couple — with geriatric spirits hovering about — as an anticipation of 1960’s superior Pornografia.

In Antonia Lloyd-Jones’s vibrant translation, the first directly from the Polish, The Possessed comes off as a spiffy, if at times slow-moving entertainment, an eye-rolling pastiche of three genres: gothic chiller, Romeo-and-Juliet romance, and detective yarn. You could call it a shaggy towel story. The gently trembling cloth hangs in a decaying caste and is believed to be infused with a vengeful ghost. This is the otherworldly force that (apparently) infests and/or threatens the souls of a cadre of lustful, greedy, bullying, and hapless characters, including a combustible pair of tennis aces (aristocratic woman, plebeian man) yearning to be lovers and an art professor who, besides totting up the value of the paintings in the castle, crusades for reason against the irrational.

The scary doings offer some ugga-bugga fun, but Gombrowicz’s anarchistic energy is tempered because it is essentially limited to spoofing cartoon scenarios. Still, this book could usefully serve as an introduction to the writer’s comically spiky sensibility. Reading it should be followed by time spent with Ferdydurke, Cosmos, and Gombrowicz’s amazing auto-biographical, polemical, philosophical, meditative masterpiece, Diary.

— Bill Marx

Tagged: "Fear and Desire", "The Beauty of the Hebrew Letter", Ducks Ltd., Evan Lewis, FYEAR, Ghost Pains, Grady Hendrix, How to Sell a Haunted House, Izzy Pludwindki, Izzy Pludwinski, James Freeman, Jessi Jezewska Stevens, Ralph P. Locke, Stanley Kubrick, Steve Erickson, Susan Miron, Tess Lewis, The Isidore Quartet