Visual Arts Review: Sampling Outsider Art in New England

By John T. Maier

Since I live in Boston, and was seeking out the farther reaches of the outsider art world, I was happy to discover three stellar galleries in Massachusetts and Vermont.

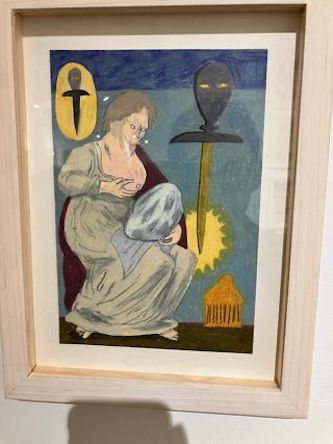

An artwork by June Gutman. Photo: John T. Maier

What is outsider art? To begin, there are outsiders in art only because there are also insiders. I don’t not know of any ‘outsider’ plumbers. If there are any, it is because they have been rejected by some union or certification board, not because they practice some especially naive and compelling form of plumbing. To be an outsider, in art or in plumbing, is to be excluded from certain conventional markers of acceptance or prestige, and to persevere in one’s work regardless.

For this reason, an Outsider Art Fair, held in New York City no less, is a paradoxical enterprise. To me, at least, art fairs always feel a touch exclusionary: who are the artists? where are the prices? how do all these people know one another? And that makes them an odd home for outsiders of any kind. But the NYC Outsider Art Fair does have a relaxed and democratic air, at least as much as any space occupied by art dealers can, and it was a pleasure to tour the space, talk with gallery owners, and most of all to see the art.

Since I live in Boston, and was seeking out the farther reaches of the outsider world, I was happy to discover three stellar galleries from Massachusetts and Vermont: Kishka Gallery (White River Junction, VT), Northern Daughters (Vergennes, VT), and Pulp (Holyoke, MA). Plotting the three of these on Google Maps yields a long flat triangle, roughly equidistant between New York and Boston. Taken together, these exhibits felt like an apt representation of that region of Western New England: rural with shades of the urban, and little of the suburban.

Kishka Gallery was displaying works by two artists: Denver Ferguson and June Gutman. Ferguson, who was born in St. Lucia and works as a cashier at a grocery store in White River Junction, creates miniature scenes and portraits of aliens and other creatures at the boundary of science fiction and the supernatural. His compressed talent and easy mastery of his materials are apparent at a glance.

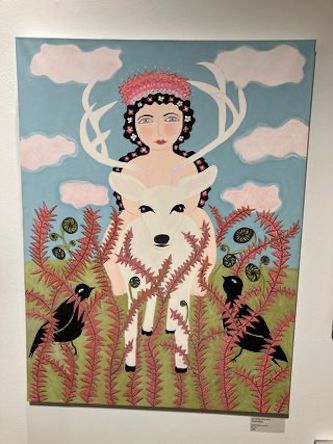

An artwork by Pamela Smith. Photo: John T. Maier

These works made a notable pairing with the art of June Gutman, who showed equal assurance in her pursuit of her own more otherworldly interests. Gutman’s work is inspired by her own experience in psychiatric hospitals as well as her subsequent withdrawal from psychiatric medications. But psychiatric themes arise obliquely in her work. The most lasting images for me were ones that reimagined traditional scenes of spiritual domesticity with a nightmarish aura: a haunted and almost inhuman Madonna with child, with a pair of disembodied eyes looking on; a woman nursing a stone that she cradles in her lap. There is an entire world here, a dark fantasy of human relationships that have been reversed or reimagined.

Northern Daughters, in contrast, put on a single-artist show that consisted of paintings by Pamela Smith. Smith is based in Vermont, as is the Northern Daughters gallery (though its physical location closed at the end of 2023, and it now exists only virtually). As with the work displayed at Kishka, there is something otherworldly about these pictures – though it is the supernaturalism of blessings and enchantment, of good magic. Maternity is a theme here too, as in Gutman’s work, though it is a decidedly more sympathetic form of maternity. Indeed, nearly all of Smith’s paintings can be seen as a painting of one woman — wreathed in flowers, cradling a child or a bird, gazing serenely and directly at the viewer. This is the ideal of the ‘good enough’ mother, reimagined as the denizen of an enchanted Vermont forest.

One of the helpful aspects of the Northern Daughters show was how it underscored the virtues of a single-artist exhibition, especially in the somewhat over-stimulating atmosphere of the Outsider Art Fair. There I sometimes found myself lost in the sheer whirl of outsiderness — the bright palettes, imperfect lines, and humanoid beings that seemed to emerge from every corner of the fair. It was a pleasure at the Northern Daughters exhibit to dwell for a moment in the vision of a single artist — Pamela Smith who, it bears noting, is the mother of one of the co-owners of Northern Daughters — and to take some time to appreciate the singular world that she has created.

An artwork by Shane Drinkwater. Photo: John T. Maier

Finally, there is the slightly more southerly but still decidedly New England space of Pulp. Here varied pieces commanded attention: Nick Quijano’s small and finely composed gouache of two ladies standing sentry at their dining room door; Shane Drinkwater’s acrylic composition of a kind of alternative solar system; Alan Doyle’s charcoal drawing of a deathlike man walking through a denuded landscape, carrying a bird before him; a pencil drawing of a zebra by Oswald Tschirtner, so austere that one is not quite sure if one is missing something (another work by Tschirtner is a chair, consisting of two uneven pencil lines); and Katarzyna Gawlowa’s painting on a wooden panel, of a morose angel taking two angry children by the hand.

The biographies of these artists also suggest the diversity of what passes as ‘outsider.’ Quijano’s paintings have a certain untutored simplicity, but he is a major Puerto Rican artist whose works hang in major collections; Drinkwater, a working artist from Queensland, attended art school in Tasmania and does decorative painting in addition to his artistic work; Alan Doyle is an independent artist, without artistic training, who lives in Dublin; Tschirtner was a patient with schizophrenia in Vienna whose drawings have attained international renown; Gawlowa was a Polish woman who began working only in her 70s on the bright and somewhat religious paintings that have brought her a surprising international celebrity.

Some critics insist that outsider artists should have no artistic training whatsoever. It is art that is often created by people who live in asylums or are otherwise excluded by mainstream society. Following that narrow construal of being an outsider, only Tschirtner qualifies. Ironically, he is perhaps by now the most acclaimed of these artists; the Museum of Modern Art has purchased his work. Taking a slightly broader position, Gawlowa and Doyle, having no formal training, might be included as well. Guijano and Drinkwater are both artistically prolific and commercially successful artists, whose outsiderdom is somewhat more theoretical, and in part geographical – Puerto Rico is far from New York, and Queensland (remote even by the standards of Australia) is still farther.

But, as noted at the outset, there is no essence of being an outsider. To be an outsider is simply to not be an insider. Indeed, the breadth and vitality of NYC’s Outsider Art Fair — prominent critic Jerry Saltz has called it his favorite art fair — is perhaps a sign of the increasing narrowness and smothering professionalism of the insider art world. Insofar as the prerequisite for a professional career in art increasingly seems to require an MFA — also something to be earned in New England, ideally in New Haven — the route to insiderdom may become even more limited. Happily, this will mean that the scope of what is considered ‘outsider’ may become more expansive, brighter, and more varied. Which may well mean that the outside will, in the end, be the place to be.

John T. Maier is a philosopher and psychotherapist based in Cambridge, MA. He received his PhD in Philosophy from Princeton and his MSW from Simmons University. He has written for Psychology Today and Slate Magazine, and has a book on addiction forthcoming with Routledge.

Tagged: Denver Ferguson, June Gutman, Kishka Gallery, Nick Quijano, Northern Daughters, Outside Art Fair, Pamela Smith, Pulp