Book Review: “Pilobolus” — Movement, at Wild Play

By Robert Steven Mack

Drawing on wide-ranging research and personal anecdotes gathered during the time he spent with the company, Robert Pranzatelli navigates us through the insouciance and absurdity of Pilobolus’ past.

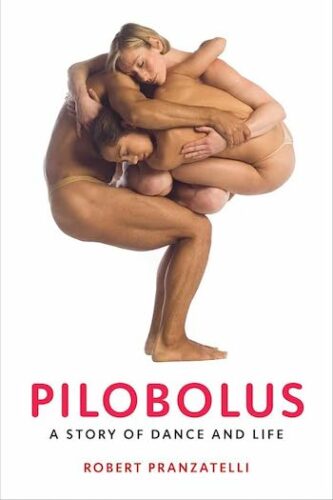

Pilobolus: A Story of Dance and Life by Robert Pranzatelli. University Press of Florida, 290 pages, illus (paper), $29.95.

Robert Pranzatelli’s history of the rise, fall, and rejuvenation of Pilobolus, an iconoclastic dance company steeped in the zeitgeist of the ’60s, explores play, conflict, and aspirations. He also relates the curious story of how Pilobolus became not simply a dance company but a collective bound by a “marriage between wit and physical sensuality” that has continually reinvented itself.

The book begins at Dartmouth College in 1971, where the group was initially germinated by an assignment for instructor Allison Chase’s composition class for non-dancers. Untethered to any strictures of technique, student collaborators Steve Johnson, Moses Pendleton, and Jonathan Wolken created a gravity-defying yet witty dance that integrated partnering and weight-sharing movements. After an informal lunch showing at Dartmouth, Pendleton and Wolken joined forces with fellow students Robby Barnett and Lee Harris (who replaced Johnson). The male quartet then set out to live and create together in the woods of Washington Depot, Connecticut.

They unwittingly named the company “Pilobolus” after a phototrophic fungi whose spores accelerate from 0 to 45 mph in a millimeter of flight and then stay wherever they land. The group embraced this phenomenon as a metaphor for Pilobolus’ spontaneous creative process. This approach was also collaborative, at least ideally — the directors choreographed together and then set the piece to music afterwards. They were not interested in using pirouettes or grand jetés — the strategy was to spotlight bodies, frequently performing nearly or entirely nude, defying gravity, moving through space, connecting, interlacing, and lifting. The pieces exist a realm between narrative and abstraction, often inspired by observations of human behavior.

Pranzatelli chronicles how what began as college distraction evolved into an innovative theater-dance that would perform on Broadway, tour internationally, and become a renowned part of the summer season at the celebrated Joyce Theatre in NYC. As the quartet garnered critical and popular attention Chase and choreographer Martha Clarke joined the group, adding polish and technique to the original quartet’s raw movement instincts. The combination of artistic strengths expanded the company’s reach, but it also led to clashes along the way.

According to Pranzatelli, the original organization of the group reflected the “late 1960s ideals of consensus decision-making and non-violent anarchism.” That sense of counterculture togetherness did not last: “the legend of Pilobolus as a troupe that did everything together — lived together, created entirely through collaboration, and functioned as a single unit — rests on its origins as a four-man group, but applied to any later configuration it contains a trace of mythmaking.” Similar to Steppenwolf and other rebellious arts organizations dedicated to egalitarian models, Pilobolus grew to the point that prosaic reality — and human nature — set in. Pranzatelli goes into how, by the mid-to-late ’70s, many of the troupe’s founders could not work together harmoniously. In fact, several of the strongest works made at that time were the result of the original members working separately. By the end of the decade, ballooning egos and clashing artistic visions tore the original Pilobolus apart. Intentionally or not, Pranzatelli provides an object lesson in the promise — and pitfalls — of polycentric or collaborative decision-making. A study in what happens when hierarchy is eschewed for collective control.

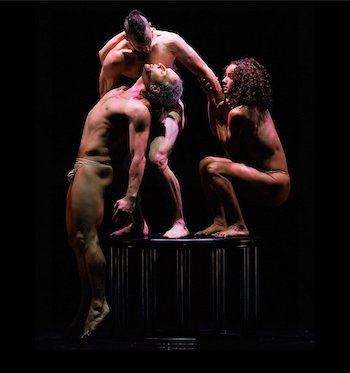

A scene from Pilobolus’ On the Nature of Things. Photo: Ben McKeown

By the ’80s, Pilobolus was still functioning, but apart from many of the founders, who had left for other ventures — for example, Pendleton started up Momix, a dance company celebrated for its innovative illusions with props and sets. Pranzatelli notes that the founders still continued to create work for Pilobolus, concentrating on using the body itself as a prop. But through it all Pendleton and company struggled to get along. Despite the troupe’s loyalty to the idea of collaboration, egos and choreographer-centric ideas of authority and ownership persisted. Until, Pranzatelli points out, the company fired Chase, the dance teacher who inspired the original Pilobolus experiment. Unable to accept her contributions as “work-for-hire,” she bitterly disputed the founders over the ownership of her choreographic work. After this quarrel, the need for some sort of hierarchical decision making became apparent. The company hired a Pilobolus outsider with no prior dance experience as executive director.

Pranzatelli also highlights how this turmoil coincided with an aesthetic shift. The “let’s make stuff” attitude left over from Pilobolus’ college origins gave way to tailoring work for corporate clients, if only as a means to stabilize — and make sustainable — the company’s finances. Understandably, to dancers caught in the middle of the transition, Pilobolus seemed to have lost its value as a communal experience.

Despite these challenges, Pranzatelli argues, the period generated innovative work because the company’s creative boundaries were expanded to include pop music videos, a collaborative Penn and Teller magic show, and a performance at the 2007 Oscars that led to the internationally acclaimed Shadowland showpieces. He details what has, to this day, become an ongoing journey as the company found, reinvented, and reclaimed its identity. Today, leadership has been rebalanced between veteran Piloblus performers and new arrivals.

Pranzatelli suggests that the company’s eclectic array of work continues to express the originating spirit of a college prank. Piloblus challenges just how far one can stretch the definition of dance. Pranzatelli rightly points out that this company, in particular, stands out as a pioneer in melding movement and theater. Pranzatelli might have made his case stronger had he discussed Pilobolus in the context of other dance movements in the late 20th century. He could have shown that, unlike (for instance) the mundane exhibitionism of postmodern dance pieces like Trisha Brown’s all-too-literal Man Walking Down the Side of Building, Pilobolus provides visual spectacle — but with dramatic substance. Delivered via lyrical movements, this probing theatricality can be abstract, humorous, allegorical, or poignant — or all four.

A scene from Pilobolus’ Megawatt. Photo: Ben McKeown

Pranzatelli also uses Pilobolus’ history to explore how art and life can interlace. At times he will linger on detailing the personal relationships of the group’s founders and directors, but he isn’t interested in gossip. He looks at how the human qualities of the founders dynamically shaped the creations that were brought on stage. When it comes to maintaining artistic institutions, collaboration and spontaneity can be messy ingredients. But that kind of egalitarian improvisational freedom can be essential when creating art. Here’s a particularly colorful anecdote from Pilobolus’ early years: on the second day of choreographing a new work, the men in the troup got collectively high on mushroom tea and then rolled around, butt naked, in the mud and rain; the women climbed up on the roof and splashed the men with water. The company took elements from this wild experience and created the primordial visuals of “Day 2,” one of Pilobolus’ most celebrated pieces. The episode also inspired the company’s signature bow — sliding naked on a wet stage to thunderous applause.

Drawing on wide-ranging research and personal anecdotes gathered during the time he spent with the company, Pranzatelli navigates us through the insouciance and absurdity of Pilobolus’ past, which turns out to be very much about its future — delving into the possibilities of dance theatre.

Robert Steven Mack is a professional ballet dancer and filmmaker. He has also written for American Purpose and The New Criterion. Robert holds a BS in Ballet from the Jacobs School of Music, a BA in History, and a Master of Public Affairs from the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Tagged: Jonathan Wolken, Moses Pendleton, Pilobolus, Robert Pranzatelli