Theater Reviews: Broadway Taps the Bookshelf — Musicals Based on “The Notebook” and “Water for Elephants”

By Christopher Caggiano

Two new musicals attempt to capture the magic of two beloved books. With mixed success …

Amid the barrage of new productions on Broadway this spring — with a daunting 14 shows still to open before the Tony deadline at the end of April — at least one significant subgenre has emerged: musicals based on classic or beloved novels. Already opened are The Notebook and Water for Elephants, which I will address in this review, and later this month, we’ll see tuners based on S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

On the one hand, it’s nice to see creators turning to literature instead of constructing the next Broadway theme park ride. (Looking at you, Back to the Future.) But these novels also represent well-established brands and are thus relatively safe for producers and their pocketbooks. Of course, there’s no guarantee any of these shows will catch on. In any given season, there’s typically only a handful of hits. But at least the marketing departments have semi-guaranteed fan bases to tap into.

The Notebook

Jordan Tyson (Younger Allie) and John Cardoza (Younger Noah) in The Notebook. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

I have neither read the books nor seen the movies of The Notebook and Water for Elephants, so I went into both productions without expectations. I somehow knew that The Notebook by Nicholas Sparks and the 2004 film adaptation were real tearjerkers, and this production delivers on that promise. In fact, the trite love-against-all-odds story is the main selling point of the musical and, hardhearted cynic that I am, I fell for it. I mean, it’s hard to imagine not getting caught up, what with the way Sparks plots out the story, and the thoughtful way that librettist Bekah Brunstetter brings it to life onstage.

The Notebook tells the story of Noah and Allie, who, despite coming from different social backgrounds, fall in love one summer in South Carolina in the 1940s. Her parents oppose the union and go to great lengths to make sure it doesn’t happen. The rest of the show revolves around Noah and Allie meeting up again later in their lives and rekindling their courtship.

The show has a framing device in which an older man is reading the story of Noah and Allie to an older woman in a dementia care facility. It quickly becomes clear that … well, let’s just say that the two older people have a very special connection to the story.

In terms of casting, there are three Noahs and three Allies at different points in their lives, and the show goes back and forth in time, eventually revealing what happened and when throughout the central relationship. The triple casting creates many opportunities for crossover and callbacks and makes for a compelling storytelling device. The downside is that we quickly catch on to how the story ends. (Or do we?)

The major disappointment in The Notebook is Ingrid Michaelson’s monochromatic score. Her music has a dull sameness here, and her lyrics are full of bland pronouncements and platitudes. I found it difficult to differentiate one song from the next. These numbers serve their purpose inasmuch as they highlight the emotional content of the story, but that’s about it.

What’s more, Brunstetter’s dialogue has a natural cadence to it that Michaelson’s lyrics lack. The scenes feel real, while the songs feel forced. I’d blame it on the fact that Michaelson writes mostly popular tunes. But we’ve seen pop writers make the successful leap to Broadway, particularly Sara Bareilles. In fact, Michaelson’s bland, interchangeable songs pale in comparison to the rich, varied score that Bareilles created for Waitress. I continually marvel at how Bareilles successfully created Broadway ensemble numbers, musicalized scenes, comic character songs, and one hell of an 11 o’clock number with “She Used to Be Mine.”

Co-directors Michael Greiff and Schele Williams do a fine job of keeping the story flowing and the potentially confusing storyline from becoming too tangled. Greiff and Williams, along with choreographer Katie Spelman, also create a lot of compelling stage pictures that take advantage of the triple casting and interlocking time frames.

There are a few moments of ham-handed imagery, particularly one scene in which the younger Noahs beckon the older man back to the older woman after he has suffered a stroke. It reminded me of some risible stage business during the most recent West Side Story revival. During “Tonight,” the Jets and the Sharks at one point were physically holding Tony and Maria away from each other. (Get it? Cuz it’s the world, not their love, that’s pulling them apart!)

Maryann Plunkett in The Notebook. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

The cast for The Notebook is extremely strong, with more than its share of adroit performers. Maryann Plunkett is simply devastating as Older Allie. Her bewildered look and heart-rending cries evoke an authenticity that will break the heart of anyone who’s lost a family member to dementia — and pretty much anyone else, too. I’m hoping that Plunkett will be the one to beat for featured actress in a musical come Tony time.

Andrea Burns is indelible in everything she does and that is certainly true here as well. Like much of the cast, she takes on multiple roles. She brings a softened efficiency to the role of the head nurse in the dementia home, but she’s especially effective as Allie’s disapproving mother, turning her into a credible person instead of just a flat villain.

Dorian Harewood brings a soft stability to the role of Older Noah. Carson Stewart is especially appealing as a cheery physical therapist in the dementia facility. Special mention goes to John Cardoza in a breakout role as Younger Noah. Full disclosure: John is a former student of mine, but he’s also a terrific performer with a crystal clear voice, a natural stage presence, and a very promising future.

Oh, and even though you might think you’ve figured out where the story is headed, you may find yourself surprised by the time the curtain rings down. Yes, the story structure removes some of the suspense, but trust me — there are still some revelations in store. Let me put it this way. If you haven’t read the book or seen the movie, and you think you’ve guessed the ending, you’ll likely find yourself right and wrong at the same time.

Water for Elephants

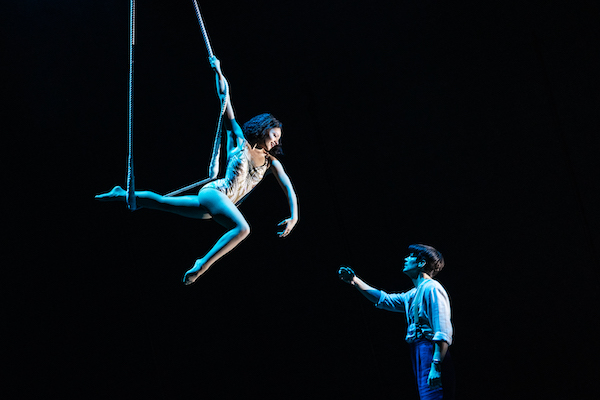

Isabelle McCalla and Grant Gustin in Water for Elephants. Photo: Matthew Murphy

So, The Notebook at least has a solid book and a well-oiled production going for it. The same cannot be said for Water for Elephants. In fact, Water for Elephants has very little going for it, apart from a talented and hard-working cast of Broadway pros.

Water for Elephants is based on Sara Gruen’s novel of the same name, which tells the story of Jacob (Grant Gustin), a young veterinary student who, during the Great Depression, leaves school just before his final exams because his parents have died in a car crash. The despairing young man becomes the vet in residence for a run-down traveling circus, whereupon he falls in love with the circus’s star performer, Marlena (Isabelle McCalla), much to the dismay of her husband, the cruel and mercurial August (Paul Alexander Nolan). Jacob also forms a special bond with an elephant named Rosie, who becomes pivotal to the story, especially the denouement.

Since the story takes place in a circus, there are plenty of acrobatic feats scattered throughout the show, regardless of whether they have any relation to where the story is at that point. These feats have been staged by Shana Carroll, co-founder of the 7 Fingers acrobatic troupe; they are indeed impressive, though they come off as distractions rather than enhancements. When the feats garner mid-number applause, it’s a sure sign that audience members are impressed by the performer rather than connected to the character or the story.

I suppose if the score and the book were doing their jobs correctly, the acrobatics might be less problematic. As I mentioned, the score for The Notebook is bland and undistinguished, but it’s a masterpiece compared to Water for Elephants’ formless conglomeration of notes and syllables. The score comes from Pigpen Theatre Co., a theatrical collective of seven people. I’m not familiar with their previous work, but based on Water for Elephants, I’m not eager to experience their full canon. Most of their numbers here don’t really register as songs so much as fragmented snatches of melody, formless daubs of sound struggling to coalesce into a full Broadway score.

Paul Alexander Nolan and the cast of Water for Elephants. Photo: Matthew-Murphy.

Oh, every now and then a discernible song appears, the first of which arrived 42 minutes into the show, a song called “Lies” for the August character. It’s not a great number, but it at least had discernible contours, unlike much of the rest of the score. In general, the lyrics are often indistinct, possibly a sound issue, but more likely because the songs lacked a perceptible structure.

Even when the lyrics can be heard clearly, they’re either banal, mis-rhymed, or improperly stressed. A recurring motif throughout the show repeatedly places the emphasis on the second syllable of “something,” “tingling,” and “Ringling,” as in Ringling Brothers. One lyric rhymes “payroll” with “table,” and many of the songs feature an infantile AABB rhyme scheme. Worst of all, the lyrics feature such groan-worthy nuggets as, “For cruelty where there should be kindness / Can only be a kind of blindness” and “But when I close my eyes, can I still trust my dreams?” Gack.

Rick Elice’s dialogue here has an artificial feel to it. Of course, Elice gave us Peter and the Starcatcher and Jersey Boys, but leave us not forget that he also inflicted The Addams Family and The Cher Show upon an innocent and unsuspecting public.

The real surprise here, at least for me, is that director Jessica Stone is the same person who shepherded the marvelous Kimberly Akimbo to success. Her work there is sure-handed and sharp, but Water for Elephants feels unfocused and wan. Frequently, it’s unclear where you should be looking or who’s singing at that moment, and that’s sort of job one for the director of a musical.

Again, the only real saving grace here is the cast of Broadway pros, but it feels as if they’re trying in vain to inject some life into the listless proceedings. The otherwise reliable Gregg Edelman, who plays an older version of Jacob, is forced and clownish here. Ideally, Stone should have worked with him to moderate his performance. Sarah Gettelfinger, who plays one of the circus performers, is likewise a very talented performer, but here she’s working too hard to oversell some bad songs. Paul Alexander Nolan is terrifically animated as August, a despicable human being, but at least he is a character who has a certain dimension to him that the other characters lack.

Both The Notebook and Water for Elephants are currently playing open-ended runs on Broadway. With all the competition this season — and so much more to come — it’s going to be very interesting to see which shows rise above the noise and settle in for successful runs. And which ones don’t.

Christopher Caggiano is a freelance writer and editor living in Boston. He has written about theater for a variety of outlets, including TheaterMania.com, American Theatre, and Dramatics magazine. He also taught musical-theater history for 16 years and is working on numerous book projects based on his research.

That you for these dead-on reviews. Having seen a preview of Elephants, I was amazed to read raves or favorable reviews from so many critics. The lyrics in Elephants are ghastly; they don’t rhyme and they often don’t even fit the music.

I don’t know what show everyone else seems to have seen. But the show I saw was pretty darned dreadful.