Jazz Album Review: “Johnny Griffin, Live at Ronnie Scott’s 1964” — A Somewhat Flawed Set

By Michael Ullman

This is a blemished set that I, a Johnny Griffin enthusiast, am glad to have.

Johnny Griffin, Live at Ronnie Scott’s 1964 (Gearbox)

By 1956, when Blue Note released its album Introducing Johnny Griffin, the tenor saxophonist Griffin had been recording for over a decade. Known as a “little giant,” (I hope he didn’t mind), he began his career on discs as a sideman for the prolific, attention-grabbing Lionel Hampton. Unfortunately for Griffin, Hampton featured his other tenor saxophonist, Arnett Cobb, on recordings. When trumpeter Joe Morris split from Hampton and started his own band, Griffin went with him. It was a way to build his résumé; he recorded under the name “Little Johnny Griffin” for Okeh in 1953.

By 1956, when Blue Note released its album Introducing Johnny Griffin, the tenor saxophonist Griffin had been recording for over a decade. Known as a “little giant,” (I hope he didn’t mind), he began his career on discs as a sideman for the prolific, attention-grabbing Lionel Hampton. Unfortunately for Griffin, Hampton featured his other tenor saxophonist, Arnett Cobb, on recordings. When trumpeter Joe Morris split from Hampton and started his own band, Griffin went with him. It was a way to build his résumé; he recorded under the name “Little Johnny Griffin” for Okeh in 1953.

By 1957 he was a sideman who had found a congenial setting: he was with the Art Blakey Jazz Messengers. That group made a record that many of us remember: Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers with Thelonious Monk. Whenever I hear “Blue Monk,” Griffin’s solo on that recording goes through my head. In 1958, he recorded as a sideman on the equally wonderful Thelonious Monk in Action.

Fame, if not fortune, was just around the corner. Featuring Blue Mitchell and Julian Priester in front of the Wynton Kelly trio, Griffin’s recording The Little Giant was widely praised when it was released in 1959. In the next few years he would record for Riverside, including a big band album, The Big Soul Band. Then he paired up with an equally distinguished tenor saxophonist, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, in a series of “tough tenor” jams, including my favorite, Lookin’ at Monk. (I have some of this music on original recordings and on so-called twofers, which are worth looking for.) The pair became popular (for jazz) as a nightclub act. At the time, I nicknamed them Griff and Gruff. Lockjaw had a big, Coleman Hawkins–oriented sound. His every note had heft as well as swing. Griffin became known for the speed and fluidity of his performances. A friend tells a revealing story about that band. Griffin had finished an exhaustingly complex solo. He looked over at Lockjaw Davis and observed: “I’m playing a million notes, and then I look at him and he’s playing all this music and doesn’t even move his fingers.” The contrast, though exaggerated in this statement, is what made their music making so exciting. Griffin led plenty of his own dates in this period, including, in 1962, the unexpected The Kerry Dancers and Other Swinging Folk, on which he plays “Black Is the Color of My True Love’s Hair” and a touching (slow) version of “The Londonderry Air (Danny Boy).”

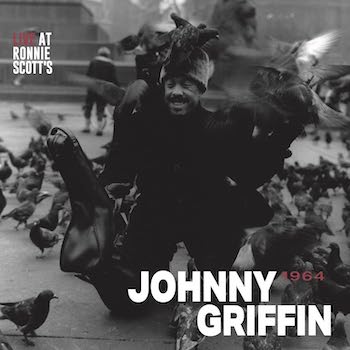

Saxophonist Johnny Griffin in action. Photo: Michael Ullman

The jazz scene was faltering in the early ’60s. Lockjaw played for a time in the Kenny Clarke/Boland band, which had been started in Paris. Griffin also moved to the city and stayed in Europe for 15 years. Hence this freelance performance at Ronnie Scott’s in 1964, where he is backed by the Stan Tracey trio, with Malcolm Cecil on bass and Jackie Dougan on drums. The band opens with a ballad that Wes Montgomery had repeatedly recorded, and that had been a staple for Judy Garland and Frank Sinatra — “The Girl Next Door.” It’s the story of a young man with a crush on a girl who barely acknowledges his existence. (He might have tried to talk to her.) Before going on, I must point out a not quite fatal flaw in this Griffin recording: Stan Tracey’s piano is ludicrously underrecorded. The sloppiness comes as a shock. Griffin opens the tune with a whimsical rendering of the melody: he holds some notes, lets others wobble, and then begins an improvisation that initially leaves plenty of space. Griffin may be quick, but he can also play subtly with the rhythm. It doesn’t take long before he reels off a fast two-bar phrase. These speed-demon phrases — with their sudden starts and stops — play effectively off the slower statements: it’s as if the saxophone stubbed its toe. Griffin builds the solo effectively, with high, choked notes, and interesting harmonic variations.

Then the bottom drops out with Tracey’s solo. I felt as if I were merely overhearing a pianist (maybe I was walking past his house?). Still, I found myself able to follow Tracey, who probably wouldn’t have played those pounding chords if he knew how meek they would sound. The quartet follows up with an uptempo version of the tune Louis Armstrong used to open his sets with and whose chords Parker used in “Donna Lee”/ (Back Home Again in) Indiana.” Here Griffin is given an opportunity to show off his agility. It’s the highlight of the set, too fast to tap your foot to. In the near absence of the piano, Jackie Dougan’s active drumming keeps the flow going, emitting brisk statements by using brushes on his snare. Griffin next plays a mid-tempo blues; it is no more than the simplest of riffs. The band finishes with a short, uptempo version of “The Theme.” This is a blemished set that I, a Johnny Griffin enthusiast, am glad to have.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

The sound quality was never very good for many of the sets recorded at Ronnie Scott’s, due to the fact they were covertly recorded. The exceptions are some recordings of Ben Webster on the Resteamed Records label, where the recording was taken straight from the mixing desk in the club and then lovingly restored by a sonic engineer before releasing it.

It’s difficult weighing up the morality of releasing poorly recorded material and having a chance to hear one’s idols playing live. Griffin and the band would have had no idea it was being recorded or that it would one day see the light of day.