Book Review: “Master Lovers” — An Inventive and Intelligent Fictional Memoir

By Vince Czyz

Master Lovers is written in a lucid, personable style, and the fictional scenes — David Winner’s recreations of history and imagined trysts — are deft, believable, and vividly imagined.

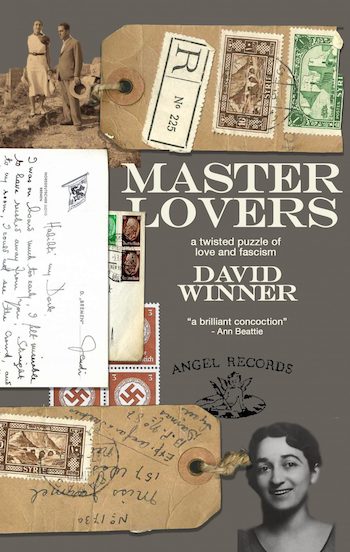

Master Lovers: a twisted puzzle of love and fascism by David Winner. Outpost 19, 276 pages.

Hybrids are hot. Categories, with their boxlike restrictions, are out. Crossovers and trans-genre writing are in. Books that are neither this nor that. Autofictions, biographical novels, essays that read like short stories.

Hybrids are hot. Categories, with their boxlike restrictions, are out. Crossovers and trans-genre writing are in. Books that are neither this nor that. Autofictions, biographical novels, essays that read like short stories.

There’s nothing new here. Jack Kerouac and Henry Miller founded their careers on autofictions. Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights is an unclassifiable — and brilliant — mix of fact and fiction that includes letters that may or may not be actual. Novels and stories that borrow elements of the essay have been authored by Melville, Hugo, Tim O’Brien, and David Foster Wallace, among others. What’s new is their popularity as a form — an indicator, perhaps, of authors’ increasing impatience with the strictures of convention.

While basing a novel on actual events can be an easy out for the writer, who, freed of the trouble of constructing a plot, bops around episodically, producing a book that reads like a series of blog posts rather than a coherent whole, histories, personal or otherwise, can also be turned into inventive and intelligent narratives. David Winner’s “fictional memoir” Master Lovers is the latter sort. Note, however, that he didn’t write his own memoir (although his presence in the narrative is all but ubiquitous); instead, he both discovered and subsequently imagined a life for Dorle Jarmel Soria, a great-aunt who outlived the 20th century: born in 1900, she died in 2002.

The way Winner embarks on his quest to find out who his aunt really was and pieces together a mosaic of her bygone world — hidden documents turn up after her death — would be a Hollywood cliché if it hadn’t actually happened. While cleaning out Dorle’s midtown Manhattan apartment, he found a diary, a collection of romantic stories she’d written as a teenager, and hundreds of love letters secreted in caches around the apartment. The letters, penned by a modest harem of men, started arriving when Dorle was in her 30s and kept coming for decades.

Dorle’s fictions and letters show a common theme: She was attracted to powerful men, glossing over their faults and exaggerating their virtues. The heroes of her romances include Dante, Lord Byron, and Paul Gauguin. Fittingly enough, she titled her story collection Master Lovers of the World. “How she loved powerful men!” Winner writes. “I thought of her Master Lovers depiction of Henry VIII, ‘no monster but a powerful, generous man with golden beard and hair, penetrating blue eyes and a ruddy face.’”

Winner was close to his aunt, and after finishing college he hung out with her every Friday night, generally accompanying her to a restaurant and listening over dinner to her talk animatedly about her storied past. Among the first women to attend Columbia School of Journalism, Dorle was an accomplished, cultured woman. She became the manager for the New York Philharmonic and, along with her husband Dario, whom she married in 1942, co-founded Angel Records. Together, they helped introduce the world to Leonard Bernstein, Arturo Toscanini, and Maria Callas.

Items Winner comes across while digging through Dorle’s memorabilia include intimate letters from Toscanini (it’s unclear whether the two were romantically involved), a photo of Dorle “yukking it up” with Mick Jagger, a note from author Paul Bowles inviting her to Tangier (she took him up on his offer), and tear-stained missives from Callas after she lost her husband, Aristotle Onassis, to Jackie Kennedy.

There’s also unexpected fallout, such as when Winner inadvertently exposes a family cover-up. This thread of the tapestry begins to unravel when Winner’s wife, glancing up at a building in lower Manhattan, sees the name S. Jarmulowsky engraved on its facade and realizes Winner’s family must once have owned the building, which had originally been a bank. So opens an episode of ancestral shame that culminates in a financial disaster for an enclave of Jewish immigrants and new surnames for the Jarmulowskys (Dorle’s became Jarmel).

The collapse of S. Jarmulowsky’s Bank, headed up by Dorle’s father and uncle, has a silver lining: Dorle is freed from the traditional restraints imposed on Orthodox Jewish women — she could no longer be married off to a respectable family — allowing her to travel, pursue a career, and meet “her master lovers on ships and at parties.”

Winner does an admirable job of making the men Dorle drew into her orbit fully rounded individuals, keeping each distinct in the reader’s mind, and of bringing a large cast of characters to life. There’s Bill Barker, a British soldier and policeman who served as a governor in British Mandate Palestine (a fragment of a letter Barker wrote is as relevant to the region today as it was then); Georges Asfar, a Syrian antiquities dealer who takes Dorle by motorcar on a gazelle hunt; a New Deal enthusiast and reporter named John Carter; English conductor and composer Albert Coates; and, among others, British-born JBS Haldane, “a founder of population genetics who cured tetanus and fought Franco.” Roughly speaking, she met the men in her life over the course of a decade, starting at the beginning of the ’30s and ending when she met Dario, the man she would marry (although letters from her suitors would continue to arrive).

Much of the book is devoted to Dorle’s passionate — and adulterous — affair with Carter, who had both FDR’s ear and Herman Goering’s. Winner is appalled that she was one degree of separation from someone in Hitler’s inner circle. “Dorle was a reliable big D Democrat,” he writes, “a great admirer of Eleanor Roosevelt…” How could she be romantically involved with a man who, it seems likely, was recruited by the Nazis to help organize a fascist campaign to win the American presidency in 1932?

David Winner, senior editor at StatOrec magazine, fiction editor of The American, a magazine based in Rome, and a regular contributor to the Brooklyn Rail. Photo: Heavy Feather Review.

One of the book’s strengths is that Winner doesn’t shy from hard truths about his family, whether it’s a racist slumlord of an uncle or Dorle’s flirtations with fascism. He writes, for example, “My spine shivers as I consider how easily Dorle countenanced the cruel way that both her fictional and real lovers mastered their worlds. Dazzled by the dashing figures cut by her lovers, Dorle didn’t seem bothered by the humans and wildlife they may have assassinated.”

But was Carter a shill for the Nazis? Winner expends countless research hours and a good number of pages trying to settle the question, and this part of the memoir reads like a well-wrought whodunit (no, I’m not going to tip Winner’s hand).

Master Lovers is written in a lucid, personable style, and the fictional scenes — Winner’s recreations of history and imagined trysts — are deft, believable, and vividly imagined. Moreover, Winner is an engaging tour guide. His insights into his aunt’s motivations, those of her various bedfellows, as well as his own give this book much of its depth. In one section, for example, he speculates on how Dorle appeared in the eyes of her lovers.

“For Georges, Dorle was an infant in grown woman form, flying in the face of her financially and sexually independent New York life to accept the role of docile Oriental mistress ….

“For John, she was the Jewess-cum-beast … fighting with animal fierceness,” particularly in the bedroom.

“For the simpler (though not simple-minded) Bill Barker, Dorle was a siren singing to the men at her dining table on the Lloyd Triestino Line, the woman who broke his heart by refusing … to be swayed by deserts and cyclamen.”

Winner has taken the disparate elements of Master Lovers and fused them into a harmonious whole. He presents his great-aunt Dorle Jarmel Soria in all her complexity and tarnished glory. Wisely, it seems to me, he also suspends judgment on her morally dubious liaisons: “I just can’t imagine her much interested in men without dark and complicated pasts in that dark and complicated decade.”

Vincent Czyz is the author of Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction that was awarded the Eric Hoffer Award for Best in Small Press; The Christos Mosaic, a novel; and The Three Veils of Ibn Oraybi, a novella. He is the recipient of two fellowships from the NJ Council on the Arts, the W. Faulkner-W. Wisdom Prize for Short Fiction, and the Truman Capote Fellowship at Rutgers University. His work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Tin House, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Copper Nickel.