December Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Dance Music

Dozage — Chrisman

Chrisman’s second album throbs with menace, summoning up images of a nightclub haunted by evil spirits. Although the Congolese producer started out within the South Africa-created gqom genre, Dozage is much more varied. (Containing 35 songs in 94 minutes, how could it not be?) Still, many of gqom’s basic tendencies remain: thick, harsh chords over polyrhythms infused with enormous, resonant basslines. Chrisman has honed his production skills working in his label Nyege Nyege/Hakuna Kulala’s in-house studio, mastering the art of mixing for full impact across the low end, midrange, and treble. His songs’ constant shifts, with a few beats held as long as a steady 30 seconds, are mapped out in great detail.

Chrisman’s second album throbs with menace, summoning up images of a nightclub haunted by evil spirits. Although the Congolese producer started out within the South Africa-created gqom genre, Dozage is much more varied. (Containing 35 songs in 94 minutes, how could it not be?) Still, many of gqom’s basic tendencies remain: thick, harsh chords over polyrhythms infused with enormous, resonant basslines. Chrisman has honed his production skills working in his label Nyege Nyege/Hakuna Kulala’s in-house studio, mastering the art of mixing for full impact across the low end, midrange, and treble. His songs’ constant shifts, with a few beats held as long as a steady 30 seconds, are mapped out in great detail.

Amid Dozage’s harsh stew, rappers Ecko Bazz and Aunty Rayzor stand out. matching the music’s battering intensity blow for blow. (Tracy the Rapper brings a more relaxed touch to her four-word chorus on “Unforgettable.”) That said, the vast majority of the songs here are instrumental. “Gbada” and “New Tech Vibe” flirt with Middle Eastern scales. Chrisman’s more accessible side owes something to trance and techno, while his hi-hats and sliding 808s borrow from drill and trap. But, more often than not, the synthesizers simply sound nasty: the trebly noises of “Itika” chatter like rattling munchkins. Percussion clangs like traffic in a busy city at rush hour. (On “Shaaa,” the drum fills do their best impersonation of a machine gun.) Song titles like “Engine Room” and “Late Siren” are remarkably accurate descriptions, as are ones that combine genres: “Tech Metal,” “Rap Gqom.”

As long as it is, Dozage maintains its grim mood, finding endless variations on its palette of textures: drawing on metallic drones as well as percussion instruments that could only exist by way of a computer. If this is mutant club music, then if offers proof that the mutation will outlive the original.

— Steve Erickson

Classical Music

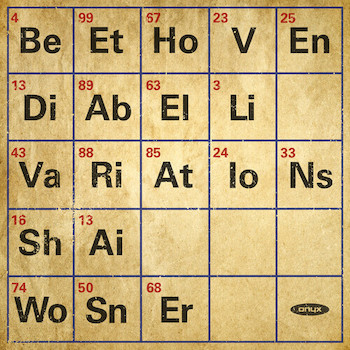

Diabelli Variations, Beethoven — Shai Rosner (Onyx)

My guess is that more people know the curious back story about Beethoven and the commissioning of his Diabelli Variations from some 50 composers (including Franz Schubert and Franz Liszt) than have actually taken the time to listen to the piece and its extraordinary 32 variations. Devilishly difficult, the piece is rarely played in public, unlike Bach’s momentous Goldberg Variations, which seem to inspire a new CD each month.

Interestingly, the stellar pianist Shai Wosner turned to performing the Diabelli Variations during the Covid-19 pandemic: “When the world shut down it was like a welcome escape from reality but also a renewable source of optimism. Escape, because the piece is in a way very much ‘about’ music, toying with all sort of styles and abstract sonic ideas, taking them apart and putting them back together again; and a source for hope because as daunting and monumental as it’s clearly meant to be, it doesn’t actually take itself too seriously. It ends with that big chord that’s both decisive and open at the same time, pointing at a future of possibility. Very few pieces manage to do that.”

Wosner (one of my favorite Schubert pianists, see my Arts Fuse review) caught my attention during the lockdown three years ago when he presented two ingenious ways in which he suggested he might be a potentially fun/serious Diabelli Variations player. Stuck at home with two small children and his wife, Shai released a You Tube video entitled “A Day in the Life of the Artist During Quarantine” using the frenetic Variation #27 as background music for various domestic happenings, including him returning, abashed, to his apartment with his laundry cart to get a mask and gloves. Then there was his series on Facebook called “The Daily Diabelli,” a pianistic soap opera bursting with humor, pathos, frivolity, deep contemplation, and wild virtuosity. All of these were lodged in my brain until I finally got a chance to hear the finished product, which puts me in an enchanted universe each time I hear it.

Given the hefty catalog of Diabellis already available on CD, there was not a high demand for yet another one. Yet Wosner’s impressive recording is moving throughout. His playing is full of exuberance and introspection, rhythmic clarity, and nuanced reflections. Each variation creates a world of its own. Recently hired on the piano faculty at Juilliard, (his alma mater), he has been touring with the Zuckerman (Pinchas, that is) Trio, as well as concertizing just about everywhere to considerable acclaim. This CD, in addition to his Schubert recordings, will only enhance Wosner’s growing reputation as a pianist with whom to seriously reckon.

— Susan Miron

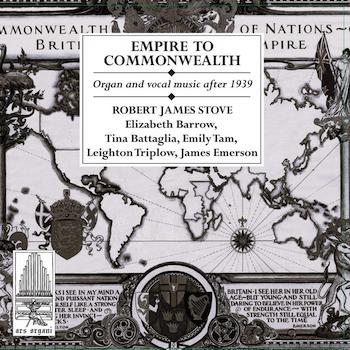

Empire to Commonwealth: Organ and Vocal Music after 1939 – Robert James Stove (TikTock Music)

My spirit was buoyed by the arrival of the fifth CD by Australian organist Robert James Stove. (I reviewed three of the others here, including a collection of English works composed just after World War I.) The new CD offers 14 shortish pieces in different moods by 14 composers who all wrote effectively for organ. Many were church organists themselves. Four of the pieces involve singers (two sopranos, a mezzo, a tenor, and a baritone). Their steady, pleasurable tones blend well with each other and with the organ, which is a very attractive and appropriate instrument built in 1920 and restored in the 1990s. (It is located in the basilica in Camberwell, a suburban area of Melbourne, Australia.)

My spirit was buoyed by the arrival of the fifth CD by Australian organist Robert James Stove. (I reviewed three of the others here, including a collection of English works composed just after World War I.) The new CD offers 14 shortish pieces in different moods by 14 composers who all wrote effectively for organ. Many were church organists themselves. Four of the pieces involve singers (two sopranos, a mezzo, a tenor, and a baritone). Their steady, pleasurable tones blend well with each other and with the organ, which is a very attractive and appropriate instrument built in 1920 and restored in the 1990s. (It is located in the basilica in Camberwell, a suburban area of Melbourne, Australia.)

The most engaging pieces, not surprisingly, come from composers who are well known for other works, such as John Ireland (a serene Intrada), Arnold Cooke (a bracingly Hindemithian Impromptu), and Alec Rowley (Sing to the Lord, using verses from Psalms 147, 105, and 106.) But I was greatly taken also with works by lesser-known figures, such as the reflective yet steadily forward-pacing Interlude XXXIX by Dom Gregory Murray, a Benedictine monk better known for two scholarly books on Gregorian chant, and the tuneful Carol of the Birds by Australian pianist William G. James. Apparently James’s much-loved carol, with its refrain line “Orana to Christmas Day,” popularized the notion—somewhat doubted by linguists—that “Orana” was an aboriginal word meaning “Greetings!”

One name might look strange: Oliphant Chuckerbutty. He came from a Parsi family (the name was originally Chakravaty) and officiated at Southwark’s Anglican cathedral. His The Queen’s Procession makes a stirring, quasi-Elgarian conclusion to this fascinating tour.

Marvelously informative and witty booklet-essay by the learned and skillful organist, whose performances let each piece make its own statement. To purchase the recording, try a track, or download the booklet, click here.

— Ralph P. Locke

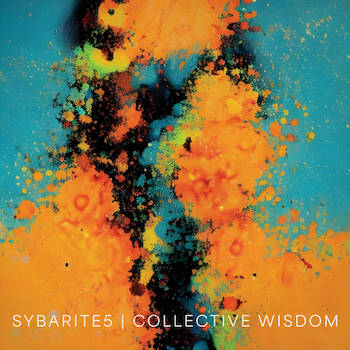

Collective Wisdom, Sybarite 5

What better way to celebrate a major turnover in membership and to remind all and sundry that Sybarite5 retains its familiar freshness, daring, and brio than for the group to bring out a new recording?

What better way to celebrate a major turnover in membership and to remind all and sundry that Sybarite5 retains its familiar freshness, daring, and brio than for the group to bring out a new recording?

That’s just what Collective Wisdom, the string quintet’s first album (Bright Shiny Things) in five years – and first since the arrival of violinist Suliman Tekalli, violist Caeli Smith, and cellist Laura Andrade — does. A mix of arrangements, improvisations, and new commissions, the disc is as unpredictable as it is refreshing: an invigorating blend of diverse repertoire, top-notch musicianship, virtuosity, and surprisingly reflective turns.

The last emerge most strikingly in a trio of works by the turn-of-the-20th-century Armenian composer/musicologist/priest Komitas. True, two of the selections — The Red Shawl and Oh Nazan — dance gamely (the latter sounds like something Dvorak might have written).

But even in those, the hypnotic melancholy that haunts the central Spring isn’t more than a single harmonic turn away. A similar delicacy marks Pedro Giraudo’s enchantingly Golijov-esque (or is it Piazzolla-like?) Con un Nodo en La Garganta and Jessica Meyer’s attractive Slow Burn.

More extroverted are Curtis and Elektra Stewart’s Manga and the opening track, Paul Sanho Kim’s arrangement of the Punch Brothers’ Movement and Location. The last — all vigor, energy, and soaring melodicism — provides the album its fantastic opening hook.

Somewhat less compelling are Jackson Greenberg’s Apartments, with its intrusive electronic element and meandering string writing, and Michael Gilbertson’s ironic Collective Wisdom. But even these have their moments — and, besides, Sybarite5 plays everything with such clarity and precision that repeated listening is all but foreordained.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

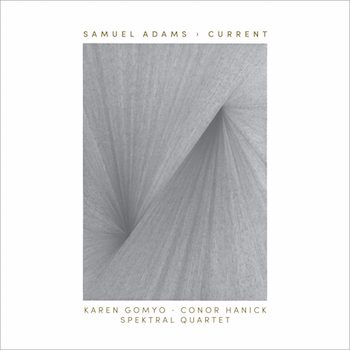

Samual Adams: Current, Conor Hanick, Karen Gomyo, Spektral Quartet

There are moments of arrival and then there are Moments of Arrival.

There are moments of arrival and then there are Moments of Arrival.

One of the latter occurs about three-quarters of the way through the second movement of Samuel Adams’s String Quartet No. 2. For the prior eight minutes, the ensemble has been vigorously passing around shimmering tremolo figurations while accompanied by a slightly unsettling halo of sound emanating from four amplified, resonating snare drums located around the group. Suddenly, those emerge in force, appearing like an anchor around which the string lines furiously orbit.

If the spot seems to have a family resemblance, that’s because it does: a similar moment appears in Common Tones in Simple Time — which was composed by Samuel Adams’s father, John. That the son has so thoroughly inherited the elder’s command of musical structure is impressive. That he’s applied it to a musical language entirely his own is remarkable.

That’s one of the big takeaways from Currents, a new recording of three Adams chamber works written between 2014 and 2020. Another is that, despite a focus on navigating the blurry line between acoustic and digital music, Adams’s is music of real expressivity.

So it goes in the Second Quartet, played here with astonishing command by Spektral Quartet. The half-hour-long effort explores no shortage of fascinating sonic combinations. But its organic structure culminates in a truly cathartic payoff at the apex of the finale.

A similar principle is at work in Adams’s Diptych for violin and piano. Again, live electronics subtly shape the work’s surface. But it’s the music’s inviting sense of rhythmic motion and harmonic direction — expertly realized here by violinist Karen Gomyo and pianist Connor Hanick — that fill out its 13 minutes so meaningfully.

Rounding out the album is the Satie-esque Shade Studies that, in Hanick’s hands, impresses for its beauty and haunting purity.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Books

The Frozen River, Ariel Lawhon — (Doubleday)

Ariel Lawhon’s sixth novel The Frozen River begins, like a good mystery, with the discovery of a body. It is November 1789 in the small town of Hallowell of pre-statehood Maine, and the body of Joshua Burgess, one of two men accused of a terrible rape, is found encased in the ice of the newly frozen Kennebec river.

Ariel Lawhon’s sixth novel The Frozen River begins, like a good mystery, with the discovery of a body. It is November 1789 in the small town of Hallowell of pre-statehood Maine, and the body of Joshua Burgess, one of two men accused of a terrible rape, is found encased in the ice of the newly frozen Kennebec river.

Lawhon’s story is inspired by the life of Martha Ballard, a real-life Maine midwife and herbalist who kept a detailed diary for much of her adult life. Except for the novel’s brief opening and closing, Lawhon’s story is narrated by Martha, and entries from her diary are included throughout. (For a fuller selection of Martha’s diary entries, see Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s Pulitzer-winning A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812.)

As a midwife, Martha is privy to many of the town’s darker secrets. She knows the rape victim, having treated her injuries and recorded the incident in her diary at the time. She also knows the second perpetrator: a well-connected former colonel in the militia and local judge named Joseph North.

Martha’s diary becomes critical evidence in the case, and she throws herself into the cause of making sure that North is brought to justice. North employs Martha’s husband Ephraim as a surveyor, so this decision carries considerable risk for her and her family. Predictably, the charges against North are downgraded to attempted rape, and he is ultimately acquitted. Nevertheless, Martha achieves a kind of rough frontier justice against the man.

Lawhon’s portrayal of Ballard has been calibrated to appeal to our modern sensibilities. She explores Martha’s daily life and family relationships, but the protagonist ultimately comes across as a static collection of 21st-century, post-feminist virtues rather than the complex human being she must have been.

Along with that, Lawhon’s prose throughout much of The Frozen River is uneven. Some passages begin with a genuinely arresting image before veering off into cliches or absurd hyperbole. The novel’s diary format — with its emphasis on chronological order — seems to hobble Lawhon at times, making her attempts to tell Martha’s backstory a bit disorienting.

Still, despite its erratic prose and awkward structure, The Frozen River dramatizes a crucial chapter in the struggle for women’s rights, an arduous process that began well before the rise of the #MeToo movement.

— Clark Bouwman

About Ed by Robert Glück New York Review Books, 269 pages, $18.95

Robert Glück’s latest novel, About Ed, is a virtuosic amalgam of discursive ruminations — part AIDS memorial, part meditation. At the center of the work, the author recounts his relationship with the visual artist Ed Aulerich-Sugai. They were lovers in the ’70s and remained close friends until his death from AIDS in 1994.

Robert Glück’s latest novel, About Ed, is a virtuosic amalgam of discursive ruminations — part AIDS memorial, part meditation. At the center of the work, the author recounts his relationship with the visual artist Ed Aulerich-Sugai. They were lovers in the ’70s and remained close friends until his death from AIDS in 1994.

Shifting perspectives and time frames interrupt the narrative throughout, a hodgepodge that includes Glück’s reminisces of the dead lover, childhood memories, portraits of elderly neighbors, dreamscapes, and travelogues. At first, this fragmented structure is confusing, but stick with it — About Ed delivers an immersive, emotionally rich experience.

The writer unabashedly celebrates sex, lots of sex. He also blurs various fictions and truths into a moving nonfiction/literary pastiche, incorporating into his melliferous prose text taken from taped recordings of his late friend as he slid into dementia and from the artist’s dream journals. Philosophical asides by the author abound, as well as his confessions of petty, unforgiven slights.

One chapter ingeniously details their ways of grappling with HIV status, a strategy inspired by the dead artist’s notes. Glück calls this book both “a novel and my version of an AIDS memoir.” As with other “new narrative” queer writers, such as Dale Peck, Kevin Killian, Brad Gooch, and Kathy Acker, the storytelling approach is nonlinear, intentionally self-conscious, and profoundly personal.

Two chapters, under the heading “Notes for a Novel,” provide a meta-view of the two decades of struggle it took for Glück to decide on the book’s final form. Elegiac and introspective, the completed manuscript turned out to be less about portraying the deceased than fending off intimations of mortality: “Do I write to remain in contact? — when I’m finished will he be truly buried?” The answer to those questions is that creating About Ed “turned into a ritual to prepare for death, and an obsession to put between death and myself.”

— John R. Killacky

Sleep Fictions: Rest and Its Deprivations in Progressive-Era Literature by Hannah L. Huber. University of Illinois Press, 185 pages.

According to a 2019 NPR report, sleep deprivation has been rising for Americans overall since at least the mid-’80s. University of Michigan clinical psychologist Todd Arnedt, who specializes in treating patients with insomnia had this explanation: “We’re a very engaged 24/7 society, and one of the first activities that gets curtailed is our sleep, and many people are just not devoting enough time to sleep at nighttime.” In fact, Americans began losing precious hours of sleep in the 1880s, and, as Hannah L. Huber’s intriguing study Sleep Fictions details, fiction writers such as Henry James, Edith Wharton, Charles Chesnutt, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman were on it sooner than scientists and psychologists, exploring with ironic dissent and humanist alarm the rise of exhaustion among Americans, white and Black.

According to a 2019 NPR report, sleep deprivation has been rising for Americans overall since at least the mid-’80s. University of Michigan clinical psychologist Todd Arnedt, who specializes in treating patients with insomnia had this explanation: “We’re a very engaged 24/7 society, and one of the first activities that gets curtailed is our sleep, and many people are just not devoting enough time to sleep at nighttime.” In fact, Americans began losing precious hours of sleep in the 1880s, and, as Hannah L. Huber’s intriguing study Sleep Fictions details, fiction writers such as Henry James, Edith Wharton, Charles Chesnutt, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman were on it sooner than scientists and psychologists, exploring with ironic dissent and humanist alarm the rise of exhaustion among Americans, white and Black.

What triggered the war on sleep? The invention of the electric light raised the economic issue of just how much rest was needed in an aggressive capitalist society. In 1895 Thomas Edison claimed that “people do not need several hours of continuous sleep, and that a few hours, or an hour of unconscious rest now and then is all that is required.” Big business, embracing the assembly-line mechanics of Taylorism, loved the idea, though expectations were soon slotted along racial and gender lines. Blacks, particularly in the South, were stereotyped as being lazy/sleepy (thus the need for sadistic discipline), while women, at least those with money, needed more repose to keep society on track.

Huber dissects the myriad forms that somnambulism could take. She takes a deep dive into the rise and fall of grogginess in James’s second novel, 1875’s Roderick Hudson, the story of an artist driven ragged by a patron who demanded more production; comes up with a fascinating examination of turn-of-the-century Charles Chesnutt short stories that dramatize how Blacks exploited white belief in their lassitude to bamboozle their bosses in the Jim Crow South; and follows Lily Bart’s struggle, as she tumbled woozily down the social ladder, to get a good night’s rest in 1905’s The House of Mirth. I had not really noticed how significant it was that the last thing Bart sees before she dies are blazing light bulbs: “She felt so profoundly tired that she thought she must fall asleep at once; but as soon as she had lain down every nerve started once more into separate wakefulness. It was as though a great blaze of electric light had been turned in her head, and her poor little anguished self shrank and cowered in it, without knowing where to take refuge.”

Huber’s chapter on proto-feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s magazine The Forerunner points out the writer’s reactionary attitudes. The social reformer wrote everything in each issue, which was published from 1909 to 1916. Among Gilman’s editorial tasks: to awaken white women to their status as somnambulists, sleepwalking their way through existence. Huber comments that “modern men, as Gilman imagines them, suffer from mismanagement and poor understanding of sleep, a weakness that could very well enable women to wake up and dismantle the patriarchy.” The flip side of this critique: other females were expected to remain torpid in their proper evolutionary slot.

Huber writes clearly; she doesn’t use jargon, though she does provide some interesting diagrams and an expansive digital companion. The book’s close readings are meaty enough to make me wish its conclusion — a look at contemporary examples of sleep fiction, such as Cloud Atlas — wasn’t so skimpy.

— Bill Marx

Tagged: About Ed, Ariel Lawhon, Christman, Clark Bouman, Collective Wisdom, Disabelli Variations, Dozage, Empire to Commonwealth: Organ and Vocal Music after 1939, John Killacky, New York Review Books Classics, Other Minds Records, Ralph Locke, Robert James Stove, Shai Wosner, Spektral Quartet, Steve Erickson, Susan Miron, Sybarite5