Book Review: Ella Fitzgerald — A Sublime American Songstress

By Douglas C. MacLeod Jr.

Biographer Judith Tick is reverent about the singer without falling into hagiography: with honest scrutiny, she asserts the enduring value of Ella Fitzgerald’s achievement for generations to come.

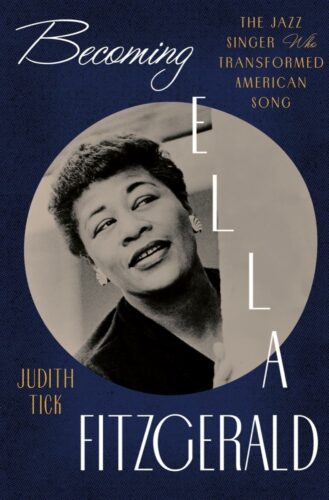

Becoming Ella Fitzgerald: The Jazz Singer Who Transformed American Song by Judith Tick. W.W. Norton, 592 pages, $40.

Judith Tick’s Becoming Ella Fitzgerald could serve as a master class in writing a contemporary biography. Tick has created a compelling narrative drawing on resources that were once hidden away, but are now accessible through 21st-century technological innovations. Tick’s stated goal: to “craft new scholarship on Fitzgerald, shining a light primarily on three neglected aspects of her life and work.” Those three areas: Fitzgerald’s experience as a touring Black songstress during Jim/Jane Crow; the singer’s familial ties prior to being placed into a girls’ reformatory school; and her private life afterwards, particularly how those personal experiences fueled her unique vocal stylings. Tick is also out to illuminate “the intellectual context of her reception as an artist,” which means evaluating critics’ commentaries and debates about her prowess as a performer. And she succeeds at her goals: Tick provides readers with a well-rounded understanding of a shy, misunderstood, underestimated woman of color who, more than anything else, wanted to be liked for who she was and the pleasure she brought to audiences around the globe.

Born in Newport News, Virginia, on April 25, 1917, to Tempie Williams (Fitzgerald) and William Fitzgerald, Ella Fitzgerald spent her first two-to-three years being reared in a working-class Black community that placed its emphasis on employment in the military and careers in music. Between 1921 and 1923, Tempie and William broke-up. Tempie met a Portuguese man who had family in a poorer community way north of Virginia — Yonkers, New York. Fitzgerald lived a good portion of her childhood and adolescence in Yonkers. Friends and teachers described her as a self-reliant over-achiever, someone who was out to make a name for herself. It was also the city where Ella started to learn more about music. The family owned both a radio and phonograph (a rarity in early 2oth-century urban communities) on which they listened to the likes of Mamie Smith, The Mills Brothers, Louis Armstrong, and others. The music also tapped into her love for dance; Fitzgerald, according to Tick, wanted to be a professional dancer, often showing off at parties to “express her sexuality.” The hope was that she would make money as an entertainer, which was a desire of many young Black women at that time. In these chapters about Fitzgerald’s early life Tick deftly provides historical context, showing how Black children (and more specifically young Black girls) of the time had big dreams but were often forced to sacrifice them because of race prejudice and/or a lack of resources.

What made Fitzgerald different? It was not only her upbringing and talent, argues Tick, but a tenacity driven by her social anxiety, fed by an incessant need to be adored. She became successful slowly but surely, surviving through the Depression doing amateur nights at the Yonkers Federation of Negro Clubs and performing throughout New York State and New York City. She got a shot at the Apollo, which led her to becoming the lead singer for Chick Webb and His Harlem Stompers. After Webb’s death, she would head up his band for about two years, then moved on to work with Dizzy Gillespie. During that time she married, had a child, and then went back to work, touring. Music critics greeted her with both praise and vitriol because of the childlike innocence of her stage persona, a naiveté that became a hallmark of her vocals and concerts throughout her career.

Biographer Judith Tick

The singer’s response to the passive-aggressive racism of journalists, promoters, and venues was understandably cautious. Yes, Fitzgerald was bringing in the crowds, but she was a Black woman. She could sing at the local club, but in many instances could not stay in the hotel just down the road. Tick does not characterize Fitzgerald as being an overt activist for the Black community. She convincingly argues that Fitzgerald’s iconic stature during the era of Jim Crow made a powerful political statement in and of itself.

As for her artistry, the key to Fitzgerald’s longevity was her development of a signature style that fit just about anywhere. Her sound was amazingly dependable, whether she was singing on the Great American Songbook recordings, taking part in live concerts with the likes of Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., etc., performing on television or for film, or traveling around in Europe with Jazz at the Philharmonic, working for producer Norman Granz. Tick speculates about where Fitzgerald stands in the annals of American popular music: was she a jazz singer? a jazz-pop singer? or a novelty singer? (Fitzgerald’s most famous song was a musical version of the nursery rhyme “A-Tisket, A-Tasket.”) The biographer never reaches a firm conclusion, but she strongly suggests that Fitzgerald should be considered a major jazz vocalist whose life offers enduring lessons.

And it is this final point that makes the richly researched Becoming Ella Fitzgerald so significant. Tick fills in many of the factual gaps in Fitzgerald’s career. More importantly, she is reverent toward the singer without falling into hagiography: with honest scrutiny, she asserts the enduring value of Fitzgerald’s achievement for generations to come. In the end, Ella Fitzgerald got what she wanted, earned, and deserved: love from her fans then, and those in the future.

Douglas C. MacLeod Jr. is an Associate Professor of Composition and Communication at SUNY Cobleskill but was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. He has written dozens of book reviews for such venues as Rain Taxi, On the Seawall, Chicago Review of Books, Penumbra, etc. for close to 18 years. He currently lives in Upstate New York with his wife Patty and their dog, Cooca. One could read more of his reviews on his blog.

Ella definitely had her own signature style and biographer Judith Tick did a superb job of her life. Did she ever mention that Ella once declared Mark Murphy her equal?? I believe Ella Fitzgerald was referring to his perfect range and scatting ability which has been proved to be superior in jazz singers both male and female.