Book Review: “The House of Doors” — Changing Skies and Expanding Visions

By Roberta Silman

Against all odds, these characters test the limits of what were considered “normal lives” at that time. The testing is what gives The House of Doors its urgency and intimacy.

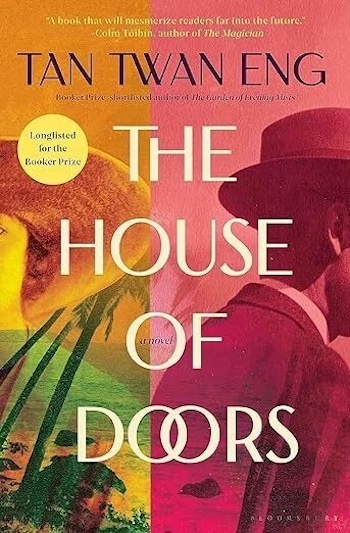

The House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng. Bloomsbury Publishing, 306 pages, $28.99.

Tan Twan Eng is a Malaysian writer in his early 50s, born in Penang, Malaysia, who has written two earlier novels: The Gift of Rain and The Garden of Evening Mists, both of which were very well received. The first was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and the second shortlisted for the same prize and a winner of the Man Asian Literary prize and the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction. Garden was made into a movie in 2019 and highly praised.

I had never heard of Eng, but I love novels in which writers play a part — like The Hours by Michael Cunningham, or The Master by Colm Tóibín. So I was delighted to receive a copy of Eng’s third novel, The House of Doors, which explores the friendship between Somerset Maugham and a fictional couple named Hamlyn. It also delves into the details of Maugham’s relationship with his luxury loving “secretary” Gerald Haxton, as well as the harrowing story of a real murder committed by Lesley’s good friend Ethel Proudlock. To top it off, we learn of Lesley’s involvement in the early struggles of the Chinese revolutionary Dr. Sun Yat Sen, a part that leads her, literally, to a house with many doors, a place where she never imagined she would be.

So here is a splendid novel in which there are many moving parts. And it is set in a place that Eng knows well and describes superbly. As we read, we are mesmerized by his evocative rendering of this strange place: its exotic smells and sounds and food, the often oppressive weather and gorgeous flora, the narrow and littered streets of the poor who serve the wealthy foreigners in their comfortable villas, as well as the secrets and mysteries that enveloped Penang’s ex-pat community in the early part of the 20th century.

What makes it even more interesting is the knowledge that Maugham — known as Willie here — used some of the very same material in his book The Casuarina Tree. Layers upon layers here will fascinate those of us who still remember the thrill of reading those Maugham novels that meant so much to us in our youth: Of Human Bondage, The Razor’s Edge, and Moon and Sixpence; layers that reflect an observation in Maugham’s indispensable book about writing called The Summing Up. It is used as the epigraph for The House of Doors: “Fact and fiction are so intermingled in my work that now, looking back on it, I can hardly distinguish one from the other.”

The novel’s frame is Lesley, widowed and now living in South Africa, in 1947. She and Robert moved there for Robert’s health in 1922, only months after Willie’s visit. Her memories of that time are sparked when she receives a copy of Maugham’s novel The Casuarina Tree. A less ambitious novelist might have been content to tell this story only from Lesley’s point of view. But part of the brilliance of this work is that we also get Willie’s take on that fateful visit, which ultimately gives him the material for the book Lesley has in her hands.

Through these alternating narrators we learn about Willie’s childhood stammer, his work as a ship’s surgeon during the First World War (like Chekhov, Maugham was trained as a physician), how he met Gerald when they were both ambulance drivers, his first meeting with Robert at a literary luncheon at Edmund Gosse’s home, their friendship growing as they became bachelor roommates, their subsequent marriages to the ever whining Syrie and the lovely patient, piano-playing Lesley, and their roles as family men when children arrived.

We are told about Robert’s career choices, his and Lesley’s marriage, her love for her life in Penang. We are made privy to Maugham’s struggles as a homosexual writer who is trapped in a horrible marriage. But then we realize why we are reading a novel about a few weeks in Maugham’s life — for this is when his previously stellar career hits a new low. On this visit to Penang in 1921 Willie discovers he has made a bad investment and lost all his money. He is faced with more pressure than he has ever faced before, and he is frightened that this turn of events means he will probably lose Gerald, as well. Here are Lesley and Willie talking one night when they both can’t sleep:

‘You’ve been looking strained since you got here,’ I said. ‘What’s troubling you?’

His face closed up. ‘Nothing at all.’ A moment later he appeared to relent. ‘Just a bit of unwelcome news … from my lawyers … I made an, ah, unwise … investment. It’s nothing too serious, but I do need to come out with a new book as soon as … possible.’

It was obvious he was more worried than he let on. ‘So that’s why you’ve shackled yourself to your desk every day. How many stories have you written?’

‘A couple …” His eyes sidled to the book on my lap.

‘But not one of them comes within a mile of “Rain”,’ I said. A pained expression flitted across his face. “Surely you’ve picked up a great score of tales on your travels?’

‘It’s not as simple as just going to some place and “picking up a few stories.”’ Willie said. ‘The story must demand to be set down on paper. With my … best stories, I always felt that I was merely the … conduit.’

I nodded slowly. ‘Like a pianist,’ I said. ‘the music doesn’t come through you, but flows through you.’

‘Quite so.’

One of the early reviews of this book complained that Eng’s prose was too detached, too even-handed, given the multiple plot twists. I don’t agree. I think Eng has struck exactly the right tone for these English people living on the Penang Island in the Straits in the early 1900s. Like all really good novels, The House of Doors is about how a small group of characters face the truth of their lives (as Lesley does about her marriage), develop new relationships, and confront a changing world — a world in which homosexuality was still a crime (the trials of Oscar Wilde in the late 1890’s hover over this book), colonization and racism were acceptable norms, adultery and murder were unspeakable scandals, and the very idea of founding a more democratic government in China is beyond rational belief. And how, against all odds, these characters test the limits of what at the time were considered “normal lives.” The testing is what gives this novel its urgency and intimacy; that’s why the restrained prose works so well.

Malaysian novelist Tan Twan Eng. Photo: Lloyd Smith

Part of the charm of this beguiling novel is also the way Eng braids some crucial strands of Asia’s history into his narrative. We learn as we read. And, as is appropriate in a novel about a writer, we are given glimpses into the creative process: how books and music and art come into being, and how, in the end, it is love — sometimes illicit — that provides the ballast in the lives of people who need to become those “conduits” whom Willie mentioned above.

Eng is also interested in the pleasures and pains of leaving one’s comfort zone. Here are Robert and Willie talking toward the end of the book when Robert explains that he and Lesley are leaving Penang for the African veld where he has a chance of living longer:

Looking at his friend, Willie felt a deep sadness for him. ‘I’m glad you invited me to stay, Robert.’

‘You’ll come and see me in the Karoo?’

‘I’ll even bring a big … box of the latest … books for you.’

‘Don’t you ever get tired of traveling?’

‘Never. I enjoy the … freedom it gives me. I feel that when I travel I can … change myself a little, and I return from a journey not quite the same … self I was.”

‘Caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt, [They change their sky, not their soul, who rush across the sea. Translation mine.] said Robert. He smiled when he saw Willie’s blank look. ‘Horace.’

‘Ah, yes, of course.’

With novels like this we readers have a chance to change our sky and expand our vision of the world. A wonderful antidote to comfort us in these perilous times.

Roberta Silman is the author of five novels, a short story collection, and two children’s books. Her latest, Summer Lightning, has been released as a paperback, an ebook, and an audio book. Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review) is in its second printing and is available on Amazon. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus and it is now available as an audio book from Alison Larkin Presents. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com, and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.