Jazz Album Reviews: Winners from Roy McGrath, Chembo Corniel, and Big Band Leaders Marcos Fernández and Arturo O’Farrill

By Brooks Geiken

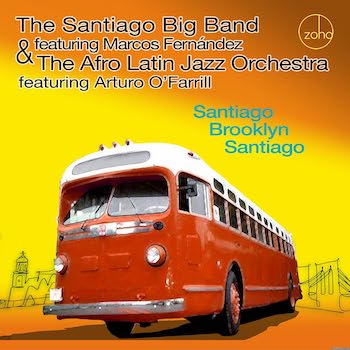

Big band leader Arturo O’Farrill points out that Santiago Brooklyn Santiago makes a forceful argument that the embargo between Cuba and the United States should be done away with.

Over the past few months I have come across three noteworthy recordings in the latin jazz field: they were albums from Roy McGrath’s superb group Menjunje, Chembo Corniel’s dynamic quintet, and an exciting team-up of two big band leaders — Cuban Marcos Fernández and American Arturo O’Farrill.

Menjunje, a Puerto Rican ensemble from the Chicago area, was named after a purportedly magical beverage your grandmother concocts when you are feeling poorly. The drink often contains whatever is at hand in the kitchen: a mix of the medicinal (such as garlic or cayenne pepper) along with sugar cane, honey, ginger, or lemon. The exact ingredients and proportions are left up to improvisational whim.

Menjunje, a Puerto Rican ensemble from the Chicago area, was named after a purportedly magical beverage your grandmother concocts when you are feeling poorly. The drink often contains whatever is at hand in the kitchen: a mix of the medicinal (such as garlic or cayenne pepper) along with sugar cane, honey, ginger, or lemon. The exact ingredients and proportions are left up to improvisational whim.

Roy McGrath, who plays tenor saxophone and leads on all the songs on Menjunje, has assembled the right combo of musicians for a vibrant journey through the consistently rejuvenating music of Puerto Rico. On any album there are usually one or two tunes or performances that are not up to snuff. Not so on here: this is a sonic joy from top to bottom, an impressively smooth, cohesively well-rounded debut from an ensemble of considerable promise.

The opening track, “Guamaní” sets things up nicely with its jaunty rhythms and punchy horns. José A. Carrasquillo’s solo on the cuatro (the national stringed instrument of Puerto Rico) supplies an apt accent. “Groove #4” starts out as a rumba (typical Cuban rhythm) then settles into a straight son montuno (a slower Cuban rhythm). Kitt Lyles’ bass solo is among the standouts here. “Antonia” takes the opposite approach: it begins as a bolero (slow ballad) and then shifts into high gear by moving into the rumba. The piano work of Eduardo Zayas earns the spotlight on “Antonia.” Trumpeter Constantine Alexander stands out in “Linda Morena,” floating above the bubbling rhythms of conga drummer Victor Junito González, percussionist Javier Quintana-Ocasio, and drummer Efraín Martínez. McGrath saves his best solo for the closing track, “Bolerito.” He lets loose after quoting a Horace Silver tune, generating furious tension via a flurry of notes.

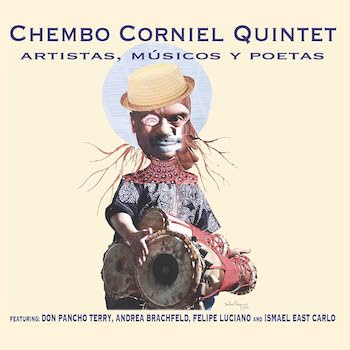

Wilson “Chembo” Corniel’s Artistas, Músicos Y Poetas makes a powerful latin jazz statement. Corniel is a very accomplished conga drummer and percussionist: his quintet consists of Hery Paz on flute and tenor sax, Carlos Cuevas on piano and Fender Rhodes, Ian Stewart on electric bass, and Joel E. Mateo on drums. The second track, “P.R.I.D.E.” (which stands for Puerto Rican Independence Development and Empowerment) draws on the words — in Spanish and English — of poet Ismael Carlo East. Andrea Brachfeld’s flute beautifully complements the empowering passions of the poet’s words. “Dalila” is propelled with precision and drive by Cuevas on the Fender Rhodes and Corniel on congas. Paz’s big tenor sound also sends the track spinning along. The acoustic piano of Cuevas and the trumpet of Agustín Someillan Garcia turn “Pa’ la Ocha Tambo”‘s sizzle up high. Corniel waits until the end of the song before unleashing his considerable chops on congas.

Wilson “Chembo” Corniel’s Artistas, Músicos Y Poetas makes a powerful latin jazz statement. Corniel is a very accomplished conga drummer and percussionist: his quintet consists of Hery Paz on flute and tenor sax, Carlos Cuevas on piano and Fender Rhodes, Ian Stewart on electric bass, and Joel E. Mateo on drums. The second track, “P.R.I.D.E.” (which stands for Puerto Rican Independence Development and Empowerment) draws on the words — in Spanish and English — of poet Ismael Carlo East. Andrea Brachfeld’s flute beautifully complements the empowering passions of the poet’s words. “Dalila” is propelled with precision and drive by Cuevas on the Fender Rhodes and Corniel on congas. Paz’s big tenor sound also sends the track spinning along. The acoustic piano of Cuevas and the trumpet of Agustín Someillan Garcia turn “Pa’ la Ocha Tambo”‘s sizzle up high. Corniel waits until the end of the song before unleashing his considerable chops on congas.

Of course, it would not be an album of Puerto Rican music without the cuatro and Juan Maldohondo supplies the indispensable magic touch on “Lagrima De Monte.” The most impressive track has to be “Evidence,” an exhilarating version of the Thelonious Monk tune. The clever arrangement — with its multiple stops and starts — puts a distinctly latin flavor on the jazz standard. Understandably, the piano comes to the forefront here; Cuevas accepts the challenge, weaving adventuresome textures in his solo. Paz is similarly inspired as he clamors up and down the register on the tenor sax.

The album Santiago Brooklyn Santiago is nothing short of a miracle. In the midst of the pandemic, Marcos Fernández and Arturo O’Farrill hatched the idea of making music with both of their respective big bands. Fernández, who hails from the town of Santiago in Cuba and O’Farrill, from the People’s Republic of Brooklyn, could not collaborate in a studio during lockdown. But, in the digital age, anything is possible. Fernández recorded the Santiago Big Band in Cuba while O’Farrill taped his Afro-Latin Jazz Orchestra via Zoom. Then came another acute challenge: who would issue the album given legal restrictions? It turns out that – if the recordings were issued simultaneously by a Cuban company (Egrem) and an American company (Zoho) (and no money was exchanged between the two countries) — international copyright laws would not be disturbed.

The album Santiago Brooklyn Santiago is nothing short of a miracle. In the midst of the pandemic, Marcos Fernández and Arturo O’Farrill hatched the idea of making music with both of their respective big bands. Fernández, who hails from the town of Santiago in Cuba and O’Farrill, from the People’s Republic of Brooklyn, could not collaborate in a studio during lockdown. But, in the digital age, anything is possible. Fernández recorded the Santiago Big Band in Cuba while O’Farrill taped his Afro-Latin Jazz Orchestra via Zoom. Then came another acute challenge: who would issue the album given legal restrictions? It turns out that – if the recordings were issued simultaneously by a Cuban company (Egrem) and an American company (Zoho) (and no money was exchanged between the two countries) — international copyright laws would not be disturbed.

To find a similar recording of this type it would be necessary to return to the ’40s and the performances of Arturo’s father Chico O’Farrill and Frank Grillo aka “Machito.” Fernández and O’Farrill dig into that fabled era on “Almendra” and “Asia Minor,” though each tune is (respectfully) reproduced with plenty of 21st century verve. Any fear of descending into serious nostalgia is averted when the bands launch into the ’70s hit, “Bilongo.” The arrangement is fresh enough to put an entirely new spin on that memorable song. Perhaps the most provocative and complex tune on the album is “Iron Jungle,” which contains a foreboding piano introduction that ventures into some intriguing shifts in tempo, including a passage in 6/8 time. The final two tracks offer a complete contrast to what came before. The new composition, “Santiago Brooklyn Santiago,” is arranged wonderfully and features fine trumpet work from Rachel Therrien. To conclude the album, the bands travel back in time to the old workhorse, “El Manisero” (The Peanut Vendor), here made to swing with aplomb via trumpet solos by the excellent Cuban musicians Alain Dragoni and Raoni Sánchez.

Blending the two big bands would seem to be an impossible task, but Fernández and O’Farrill pull it off with resourceful skill. The sound of the album is full, but always balanced: the bands complement each other — there is no evidence of competition.

In the album’s liner notes, O’Farrill explains how Santiago Brooklyn Santiago came about. At the turn of the century the bands had an opportunity to perform together at a festival in Cuba. Twenty years later they wanted to combine their talents again. The dream was realized, but only after the groups surmounted considerable obstacles. Now everyone can enjoy these cross-cultural sounds. O’Farrill goes on to point out that Santiago Brooklyn Santiago makes a forceful argument that the embargo between Cuba and the United States should be done away with. Let the music flow, free of any anachronistic political hassles.

Brooks Geiken is a retired Spanish teacher with a lifelong interest in music, specifically Afro-Cuban, Brazilian, and Black American music. His wife thinks he should write a book titled “The White Dude’s Guide to Afro-Cuban and Jazz Music.” Brooks lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Tagged: "Artistas Músicos Y Poetas", Arturo O'Farrill, Brooklyn, Chembo Corniel, latin jazz, Marcos Fernández, Menjunje, Roy McGrath, Santiago