Opera Album Review: An Engaging Opera by an 18th-Century Black Composer

By Ralph P. Locke

Joseph Bologne, whose mother was a slave in Guadeloupe, proves to be as skillful in vocal-dramatic music as we have long known he was in instrumental works.

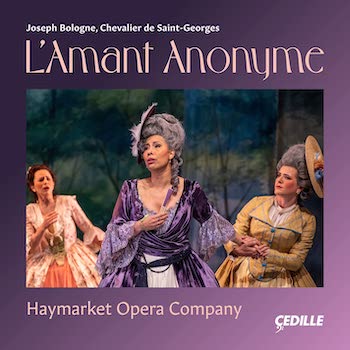

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges: L’Amant anonyme

Nicole Cabell (Léontine), Nathalie Colas (Dorothée), Erica Schuller (Jeannette), Geoffrey Agpalo (Valcour), Michael St. Peter (Colin), David Govertsen (Ophémon).

Haymarket Opera Orchestra, cond. Craig Trompeter.

Cedille 90000217 [3 CDs] 99 minutes [incl. spoken dialogue], 72 minutes [music only, on CD 3]

The recent search by scholars and performers for largely forgotten composers of non-European extraction has brought some highly proficient and occasionally marvelous works to the attention of concertgoers and CD collectors alike. In these pages (or however one says it nowadays), I have reviewed recent recordings of music by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Florence Price, William Grant Still, and Margaret Bonds, as well as the searing opera Blue (music by Jeanine Tesori), whose libretto, about police brutality in America’s cities, is by the noted Black stage director Tazewell Thompson.

The recent search by scholars and performers for largely forgotten composers of non-European extraction has brought some highly proficient and occasionally marvelous works to the attention of concertgoers and CD collectors alike. In these pages (or however one says it nowadays), I have reviewed recent recordings of music by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Florence Price, William Grant Still, and Margaret Bonds, as well as the searing opera Blue (music by Jeanine Tesori), whose libretto, about police brutality in America’s cities, is by the noted Black stage director Tazewell Thompson.

Here we have the first recording of a comic opera by Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, whose dates are 1754-1799. The essay-booklet often calls him simply Bologne, which perhaps has the advantage of allowing him to become a “real” name in the roster of composers who were his contemporaries but carried no title of nobility. But I love that he was a Black aristocrat, so I stick with the more customary appellation.

The Chevalier’s astounding life story has been well told by Gabriel Banat (himself a professional violinist who played for years in the New York Philharmonic). Banat wrote the Saint-Georges entry in Grove (www.oxfordmusic.com) and told the man’s story more fully in a book entitled The Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Virtuoso of the Sword and the Bow (2006; now available Open Access).

Record collectors may know some of the eight or more CDs of the Chevalier’s instrumental works. There is also a 2016 DVD about his life (featuring performances, again of instrumental works, under Jeanne Lamon). And the 2022 feature film, Chevalier, based on his life, though no doubt a bit freely, has been much praised.

The pieces by Saint-Georges that have been heard most widely are the four that make up vol. 1 of the pathbreaking multi-LP “Black Composers” series that Columbia released in the mid-1970s. The orchestral works in the series were conducted by Paul Freeman. The “Black Composers” recordings were often broadcast on the radio and used in classrooms. The “Black Composers” series was rereleased as a 10-CD set by Sony Classical in 2019 (available now for under $40—that is $4 per disc!).

That Saint-Georges LP from that series (now CD 1 in the Sony rerelease) includes a symphony, a symphonie concertante for two violins and orchestra, a string quartet, and an aria from one of his four operas, Ernestine. The symphonie concertante comes across with great vitality and precision, thanks to renowned violinists Jaime Laredo and Miriam Fried. And Boston Baroque, under Martin Pearlman, has put online the score of his Violin Concerto in D, Op. 3, no. 1, and has released a live recording of it featuring Christina Day Martinson.

Here we have the first recording of the only one of Saint-Georges’s operas to survive more or less completely. It has been edited for performance by Gregg Sewell; I’d have liked to read some explanation of what Sewell fleshed out or clarified. (I looked him up: he’s a professional music engraver, a prolific composer, and director of music ministries at a Presbyterian church in Illinois.)

I came to the recording with great expectations but also with some trepidation because Saint-Georges (or Bologne, if you prefer) has in recent decades been tagged with the unfortunate phrase “the Black Mozart.” He was, in a way, both less and more than this. He was born in or around 1745, the son of a French planter and nobleman on the island of Guadeloupe and a teenaged woman known as “Nanon,” who was enslaved to the planter’s wife. In 1753, the father returned to France with his son (the ship’s manifest describes the latter as “mulatto Joseph”) and arranged for him to gain musical training and a broader education. Joseph became a master at fencing and also at playing the violin: by the year 1769, he was performing in the important series led by Gossec known as Le Concert des Amateurs. Two years later he became its concertmaster. And another two years later he moved over to lead the orchestra of the highly esteemed Concert Spirituel series. He reportedly was in the running to head the Paris Opéra (Académie Royale de Musique) but the opposition from some of the singers to his racial origins caused him to withdraw his name from consideration.

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges — the first recording of the only one of his operas to survive more or less complete.

When the Revolution came, Saint-Georges took on a new role: as the colonel leading a military troop (consisting of what were at the time called “free Blacks” or “free people of color”) that helped protect France against counterrevolutionary forces. During the Terror, he was imprisoned for over a year, but, thereafter, he returned to leading an orchestra, this time one called Le Cercle de l’Harmonie (The Circle of Harmony). He died in 1799 of an “ulcerated bladder.”

L’Amant anonyme comes from the middle of Saint-Georges’s event-filled life. It was most likely first performed in the theater of a private residence (that of the Marquise de Montesson, an amateur actress) in 1780. It has two female singing roles, three male singing roles, a chorus of villagers, and one nonsinging part (perhaps taken by the marquise): that of Dorothée, the confidante of Léontine.

The plot, which derives indirectly from a novel by the renowned Mme. de Genlis, involves a young man, Valcour (tenor), who is secretly in love with the noble Léontine (soprano) but fears being rejected by her. Her tutor, Ophémon (baritone), encourages Valcour to send a love letter, anonymously, to Léontine. Complications ensue as Léontine struggles with conflicting feelings for the seemingly duteous and unimpassioned Valcour (he steadfastly refuses to let her know that he has even the slightest interest in her) and for her fiery, if anonymous new suitor.

Eventually, of course, she learns that Valcour and the “anonymous lover” are one and the same. But a fair amount of humorous action and dialogue take place along the way, partly involving Léontine’s confidante, Dorothée (the spoken role). Another pair of lovers, the peasants Jeannette (soprano) and Colin (tenor), become part of the action, presenting a contrasting view of love — among the lower classes — as natural and openly confessed.

There are pauses for onstage songs (that is, songs that the characters sing for one another, as opposed to arias in which feelings are confided intimately or simply “thought” in soliloquy) and various lovely dance numbers. For that matter, even the arias and larger ensembles are often imbued with a dancelike lilt that makes for delightful listening. The work concludes with a quartet for the two pairs of lovers (highborn and lowborn) and a dance for everyone on stage (contredanse générale).

Singer Nicole Cabell Photo: Eastman School of Music

Despite the Chevalier’s modern-day nickname (“the Black Mozart”), the music of this opera doesn’t sound much like Mozart’s. Rather, it sounds more like that of Grétry, the leading French opera composer of the day. (Grétry may have given Saint-Georges lessons in composition.) The opera’s arias, duets, and a trio and quartet are mostly short but beautifully laid out, melodically attractive, dramatically apposite, and effectively, if unobtrusively, orchestrated. The heroine gets three major and well-constructed solos that, together, sketch out the development of her increasing attraction to Valcour. Toward the end we get a relatively complex duet for the two main lovers in which Valcour finally confesses his feelings, and a very satisfying trio for the two plus Orphémon, the character who had played such an active role in keeping them apart in order (it becomes clear) to bring them together. The choral parts are performed here by the five singing characters plus the soprano who otherwise takes the spoken role of Dorothée.

The singers are all a pleasure to listen to, never forcing their voices beyond what is appropriate to a chamber opera of the period. The big star is Nicole Cabell, in the central role of Léontine. Cabell won the Cardiff Singer of the World award in 2005 and has performed lyric and coloratura roles (Fiordiligi, Adina, Leïla, Musetta) in major opera houses, including the Met, Chicago Lyric, and Covent Garden. She has also sung in recitals and in orchestral concerts, often in works by modern American composers, such as Kevin Puts. I have noticed at least nine previous recordings that feature her, including an aria disc conducted by no less than Joan Sutherland’s renowned conductor-husband Richard Bonynge.

Cabell here keeps her soaring voice nicely in check. She negotiates the many little florid passages with ease and flair, as do all the other singers. I see that she is now on the faculty of the Eastman School of Music, where she received her undergraduate training two decades ago. (I vividly remember her captivating performance there in Poulenc’s La Voix humaine.)

The six singers have great success, too, with the extended spoken-dialogue scenes (some lasting over four minutes). The words are pronounced better and more meaningfully here than what I have heard in certain performances and recordings of, say, the original version of Donizetti’s La Fille du régiment. Perhaps the nonnatives were helped out by the one French-born person here, Nathalie Colas, whose rendering of the dialogue (as Dorothée) is utterly exemplary.

The recording consists of three CDs: the first two contain the entire work; the third, the musical numbers only. (On at least one streaming service the tracks are presented in the same order. To hear only the musical numbers, start at track 34.) The booklet offers a savvy and well-informed essay and synopsis by musicologist Mark Clague, plus the libretto in French and an excellent translation. This is the way any previously unrecorded opera should be ushered into the world. Best of all, the music is spiffily performed, not just by the singers but also by the small chamber orchestra (using period instruments) under the alert direction of Craig Trompeter.

W.A. Mozart — perhaps he should be dubbed “the white Saint-Georges” or “the white Bologne.”

I’d like to come back to that modern nickname, “the Black Mozart.” It’s problematic on numerous grounds. Not least: Why should any composer be held up for comparison to one of the greatest who ever lived? But another objection is that, if the Chevalier’s instrumental pieces (which he’s best known for) sound like Mozart’s at times, which they do, it’s largely because both composers were drawing from the compositional norms of the day (e.g., the music of Johann Stamitz, J.C. Bach, and Haydn). Furthermore, Saint-Georges was one of the prominent French composers of symphonies concertantes: essentially, concertos with two or more soloists. Mozart knew this France-centered genre well and he reflected it in his superb Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Viola, and Orchestra (1779). So, as some have recently pointed out, maybe Mozart could be dubbed “the white Saint-Georges” or “the white Bologne” (which sounds a bit like a sort of luncheon meat)!

Fortunately, the CD booklet does not engage in such folderol. All praise to Cedille Records (founded in 1989 by Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s son James) and to the Chicago-based Haymarket Opera Company for this substantial resurrection of a typical work from pre-Revolutionary France, composed by a remarkable individual who was himself at once as typical yet atypical as one could be at the time.

The recording was made possible, in part, by contributions from several dozen donors, aptly listed in the booklet. This relatively new model for funding classical music is also being used by, among others, Opera Rara (in the UK) — as of course it has long been used, in the US, by symphony orchestras, museums, hospitals, universities, places of worship, and (for better or worse) social- and political-action organizations.

By the way, the classical-music world has become, in recent decades, increasingly open to individuals from diverse backgrounds. Chicago-born Geoffrey Agpalo is of Filipino descent, and California-born Nicole Cabell has discussed in a published interview the challenges of being, as she expressed it, “of mixed race” (Black, Korean, and, to use the interviewer’s word, Caucasian). These marvelous singers are rightly valued for their skill and insight rather than for their skin tone or facial features. The Chevalier de Saint-Georges might be happy to know that some things in the classical-music world, at least, have been changing for the better in recent decades.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.