Book Review: August Wilson — Poet, Pugilist, and Playwright

By Robert Israel

Patti Hartigan’s biography is a workmanlike portrait of dramatist August Wilson that never delves deep enough into his poetic soul.

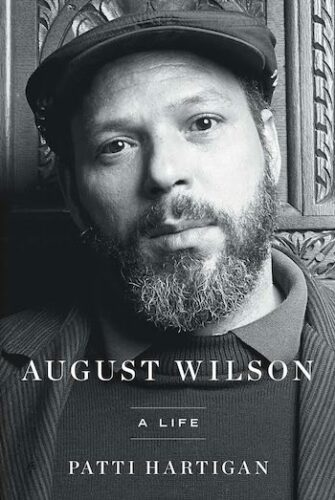

August Wilson: A Life by Patti Hartigan, Simon and Schuster, 544 pages, $32.50.

I met playwright August Wilson (1945-2005) at Penumbra, an African-American troupe, in St. Paul in 1979 when I was writing for a Twin Cities weekly paper. Wilson had a day job as a writer at the Minnesota Science Museum. He introduced himself as a poet, but looked like a pugilist, as if he had just stepped out of the boxing ring. He had a self-assured demeanor and a randy glint to his eye. Wilson made it clear that, when it came to writing, he’d only settle for delivering knockout punches and would never exit the boxing ring unless he held his hard-won trophy aloft. A group of us, mostly ink-stained wretches, would retreat to a local bar after performances in which we’d marvel at his impromptu poetic recitations, words gushing forth in rhyming torrents. During these alcohol-fueled sessions, Wilson embodied this description, from a poem by Sylvia Plath: “You leave the same impression of something beautiful, but annihilating.”

At the time, there were no poetry slams. Their precursors, in the African-American tradition, were called “toasts,” memorized vocal narrations of sexual conquests and violent altercations spoken aloud via bawdy, musical rhymes. In this genre, Wilson had a rival, the African American poet Etheridge Knight, who lived nearby in South Minneapolis. My feeling is that Knight could have gone a few rounds with Wilson and possibly bested him. Knight was an ex-convict, a disabled Korean War veteran, and a recovering drug addict. I attended several of his mesmerizing poetry recitals at the Cedar Riverside People’s Center. “Run sister run — the Bugga man comes!,” Knight chanted from his gut-wrenching poem “The Violent Space, (or when your sister sleeps around for money).” If the two poets ever met in real life — after all, they occupied the same “violent space” — I have found no record of it.

Patti Hartigan’s authorized biography of Wilson, August Wilson: A Life, contains only a few brief citations of Wilson’s poetry. She explains that “the August Wilson Estate declined authorization.” Sadly, this omission results in a huge loss when it comes to understanding, and appreciating, Wilson and his writing. Time magazine insisted that Wilson wrote “pure poetry” that was drawn from a deep well. One finds many “toasts” in his plays, verbal jousts between characters, intoned with the same mesmerizing torrent of words he used during those St. Paul booze sessions that illustrated what he called “blood memory,” streams of language that tapped into what he claimed were ancestral roots that stretched back over the centuries.

Wilson wove these “blood memories” forcefully into his plays, beginning with Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, first developed at the O’Neill Center in Connecticut, then at Yale Rep, and finally on Broadway, and in Fences, which had a similar development arc and went on to win both the 1987 Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award (both plays were later made into films). It was during the tryout run of Fences in New Haven, starring James Earl Jones, that I was reintroduced to Wilson by the late Trinity Rep actor Ed Hall (who gets a special mention in Hartigan’s book). Hall, a favorite of Wilson’s, was my neighbor from Providence; he premiered the role of Bynum Walker in Wilson’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.

Hartigan takes us behind the scenes, looking at the stressful business challenges Wilson faced, particularly when he sparred with wealthy sponsors and exploitative lawyers. She offers some sharp glimpses into Wilson’s private life, describing his voracious proclivity to pursue women in extramarital affairs. She examines the consequences of his infidelities, namely that two out of his three marriages ended in divorce. Wilson was also given to fits of violent temper, and Hartigan describes his outbursts of rage in unsparing detail. Those close to him attributed his anger as the product of his troubled youth. Born Frederick August Kittel, Jr., Wilson endured poverty and racism during his formative years and dropped out of school at age 15, living hand-to-mouth in his hometown of Pittsburgh as he developed his artistic métier.

Robert Cornelius, Shannon Lamb, Maurice Emmanuel Parent, and Stewart Evan Smith in the Huntington’s 2022 production of August Wilson’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. Photo: T Charles Erickson

Wilson benefited from tutelage by disciplined directors, theater critics, and dramaturges, among them Michael Feingold, Edith Oliver, and Yale Drama School dean Lloyd Richards, who helped him shape his scripts for the stage. Before succumbing to cancer at the age 60, Wilson had finished 10 scripts that chronicle, decade by decade, the Black experience in America in the 20th century. He was awarded a second Pulitzer Prize in Drama in 1990 for The Piano Lesson.

Hartigan also reveals that Wilson was a bit of a “fabulist,” and she cites instances in his late career autobiographical work, How I Learned What I Learned, that were outright lies. These embellishments do not diminish Wilson’s accomplishments or tarnish his artistry, which was profound. American authors, such as Mark Twain and Ernest Hemingway, have indulged in expansive egotistical fancies: they were, like Wilson, fiction writers. Hartigan also reports that, near the end of his life, even after learning of his dire health issues, Wilson never stopped working, mulling over writing a novel and screenplays (several scripts were left unfinished at the time of his passing).

Hartigan’s writing style is dry and reportorial, honed during her years at the Boston Globe where she was an arts reviewer and reporter. While this disciplined approach works well when it comes to resuscitating the multifarious facts of Wilson’s life, it fails to capture the combustible passion that Wilson — as playwright and poet — infused into his works. As a biographer, she has the nagging habit of repeating details, sometimes on the same page, and often within later chapters, that even casual readers will have already absorbed at first reference. She seems oblivious to the fact that readers possess the intelligence to recall multiple details — that there is no need for her to insert pesky reminders.

What we get from Hartigan’s book is a workmanlike portrait of August Wilson, a dutiful timeline that never delves deep enough into his poetic soul. Wilson emerges as a writer who fought hard, kept his eyes on the prize, and accepted nothing less than triumph. He was a champion in the boxing ring that is the American theater.

Robert Israel, an Arts Fuse contributor since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

Tagged: August Wilson: A Life, August-Wilson, Black History, Black theater Black playwright

I agree — thank you.