Theater Feature: Favorite Stage Productions of 2022

Compiled by Bill Marx

Our theater critics pick some of the outstanding productions in a year haunted by COVID.

Robert Israel

Robert Cornelius, Shannon Lamb, Maurice Emmanuel Parent, and Stewart Evan Smith in August Wilson’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone at The Huntington Theatre Company. Photo: T Charles Erickson

Best Stage Production of 2022: The Huntington Theatre Company’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.

Despite minor miscasting and missteps, the HTC’s reprisal of August Wilson’s two-act play held true to his vision, poignantly telling the story of African Americans emerging from the scorched earth of the American South after the Civil War in search of “a song” within themselves to sing — and new lives.

A standout from the cast, Shannon Lamb, brought her sublime acting chops to the role of Bertha Holly. A switch of her arm and the steely gaze of her all-seeing eyes established an indelible feistiness. Unfortunately, Wilson doesn’t adequately develop Holly’s role in the drama. Call it an early career shortcoming — Wilson wrote meaty roles for males, less substantive roles for females. LaTanya Richardson Jackson, director of the current Broadway revival of Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play The Piano Lesson, told the New York Times that she had confronted the playwright on this very subject.

“August was such a man’s man,” Jackson said. “[But a woman’s] presence should not be something that’s taken for granted. Our presence is important.”

Ms. Jackson (her husband, actor Samuel L. Jackson, stars in the Broadway staging), recalled that Wilson promised he’d do better. And he held true to his word. Give a listen to/look at Tonya, a character created for his play King Hedley II — with its stirring monologue.

What made the HTC’s reprisal of Joe Turner especially praiseworthy? Audiences got a riveting version of Wilson’s drama, blemishes and all, along with a chance to see Lamb make more from less via a knockout performance.

**

R.I.P. – Michael Feingold

The late Michael Feingold accepting the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism in 2015.

Michael Feingold who wrote for the (now-defunct) Village Voice, died on Nov. 21 in New York at the age 77. I met him at A.R.T. during the pre-Paulus flash-in-the-pan days when he served as a literary manager, tasked with shaping plays for the stage (a skill he later deftly applied to August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom). A gifted translator from the German, he gave us definitive English version of the collaborations between Bertolt Brecht’s and Kurt Weill. For decades he wielded a sharp critical pen. Here’s a snippet from his review of Neil Simon’s play Rose’s Dilemma: “It doesn’t mean anything to anybody and doesn’t reveal any understanding, on its author’s part, of how plays are written.” A link to an archival selection of Feingold’s pieces can be found here.

Robert Israel can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

David Greenham

Another year in the books, my seventh with the Arts Fuse. I’m gratified to note that there were several highlights.

I didn’t think that A.R.T.’s bold revival of 1776 hit all the marks. But the show’s opening moment, when the diverse cast of women and LGBTQ actors marched downstage to transform into the “founding fathers” was memorably dynamic.

Last spring, Portland Stage’s set designer Anita Stuart, who also serves as the company’s executive and artistic director, created one of the best sets I’ve ever seen for Sabina, a new Willy Holzman play with music by Louise Beach.

Another standout experience: Mark H. Dold’s precise and emotional performance as Morgan in Matthew López’s epic two-part play, The Inheritance, produced by Speakeasy Stage last spring.

There were three full productions that I really loved this year.

A scene from the Portland Theater Festival’s production of Pass Over. Photo: Kat Moraros

The newly created Portland Theater Festival held its second season during the summer with three productions. Antionette Nwandu’s bold 2017 one act, Pass Over, succeeded as a flame-throwing riff on Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

Just a couple of weeks ago, American Repertory Theater triumphed with their slick new production of Life of Pi. Both Mark Favermann and I wrote about this production for the magazine. Mark focused on the amazing design, outstanding immersive stagecraft, and the stunning anthropomorphic puppets. (A note from editor Bill Marx rightly reminded readers that the animals and fish depicted by the show’s puppets are in grave danger because of the accelerating extinction of wildlife around the world.)

For me, the video design by Andrzej Goulding, lighting design by Tim Lutkin, and sound design by Carolyn Downing were the most praiseworthy elements in Life of Pi. The textured videoscape, in particular, was enormously effective and beautifully executed.

There’s still time to catch the show in Cambridge before it transfers to Broadway in March. Whether it’s the puppets, the videoscape and tech, the lovely acting and directing, or its compelling theme (animals and people on our planet are under threat), Life of Pi is sure to enthrall and provoke.

One production left me speechless this year, and it surprised the hell out of me because I’m not usually at a loss for words. However, Ain’t Misbehavin’ – The Fats Waller Musical, co-produced last spring by The Nora@Central Square Theater, The Front Porch Arts Collective, and Greater Boston Stage Company, was nearly perfect. At the time I called it “one of those one-of-a kind of experiences that we all long for in the theater. It’s when the tech, the direction, the cast, and the artistic staff mesh and then soar.” Equally surprising is that the show itself — a Fats Waller musical review with no real story line — is structurally flawed. No matter, the talented cast under the direction and choreography of Maurice Emmanuel Parent sparkled.

The opportunity to sit through these three strong productions along with dozens of other outstanding theatrical moments is a pleasure (and well worth the drive it takes to come down from Maine to see the shows).

But the biggest development of note in theater this season was the encouraging reality of diversity. Of the 20 productions I reviewed for the magazine in 2022, 12 of the shows revolved around Black, Asian, Middle Eastern, Eastern European Jewish, or LGBTQ leading characters.

Those efforts included: English by Sanaz Toosi, The Chinese Lady by Lloyd Suh, Paradise Blue by Dominique Morisseau, Pass Over by Antoinette Nwandu, Life of Pi, based on the novel by Yann Martel and adapted by Lolita Chakrabarti; Sabina, written by Willy Holzman, music by Louise Beach, lyrics by Darrah Cloud; Young Nerds of Color, arranged by Melinda Lopez; Our Daughters, Like Pillars by Kristen Greenidge; AntigonX by Shey ‘Ri Acu’ Rivera Rios; The Inheritance, Part 1 and 2 by Matthew López; Central Square Theater’s Ain’t Misbehavin’, Speakeasy’s Once on this Island, and A.R.T.’s 1776.

Critics have been begging for theaters to take more risks by bringing in new voices. It is wonderful to see that it is happening on our stages. Let’s hope that trend continues into 2023.

David Greenham is an adjunct lecturer of Drama at the University of Maine at Augusta, and is the executive director of the Maine Arts Commission. He has been a theater artist and arts administrator in Maine for more than 30 years.

Bill Marx

A scene from the Double Edge Theatre Company production of The Hidden Territories of the Bacchae.

The Hidden Territories of the Bacchae: A Response to Euripides’ The Bacchae. Conceived, directed, and designed by Stacy Klein. Co-created and adapted with Milena Davova, Jennifer Johnson, Travis Coe, and Carlos Uriona. At the Double Edge Theatre, 948 Conway Road, Ashfield, MA. Closed.

George Bernard Shaw once wrote that the critic’s revenge on actors and directors who dismissed their reviews is that the journalist’s descriptions of stage productions are all that history would remember. Critics had the final say — at least in the days before the arrival of videotape and film. What GBS didn’t see is that in some cases it might be the lambasted theater artists — if their artistic vision grows and expands over time — who can make a fair claim to having “the last word.”

40 years ago, in April 1982, I reviewed the Double Edge Theatre Company’s premiere production, Rites, a modernized version of Euripides’s The Bacchae. I panned it on WBUR, calling it a “shrill production [that] fulfills just about every nightmare or cliché anyone has ever had about bad feminist theater lusting for male blood.” I had a point: after all, a plastic boy doll was flushed down a toilet by a group of women crazed by their hatred of men. But time has proved that I reached for a tomahawk when a scalpel was called for. I was right and wrong about Rites. I missed what the Boston Globe stage critic John Engstrom saw in the production — that artistic director Stacy Klein, though confined to the claustrophobic environs of the ICA space, enlivened the proceedings with a nimble sense of ritual and choreography. And it turns out that, over the decades, Klein’s skillful manipulation of ceremony and movement, combined with music, visual iconography, and what could be described as spiritual chutzpah, has matured in impressive ways.

Ensconced in its current spacious home on a farm in Ashfield, the company went back to the future last summer and celebrated its 40th anniversary with a zesty production of a new version of The Bacchae. The staging was a marvelous bookend to the earlier production — it was a soulful act of aesthetic homage. Unlike Rites, which embraced revenge, madness, and destruction, this adaptation sent a cadre of vocalizing, acrobatic, and beneficent Bacchae scampering across green fields, doing acrobatics in the barn, and swimming in a pond. In terms of dramatic power, I wish the staging’s revisionism (see Euripides’s rip-roaring original) had not been so thorough — the tragedy’s murderous anarchy was pretty well banished. But the evening was a reminder that it has been a privilege to witness the birth of what turned out to be such an adventurous troupe, and to be in a position to appreciate just how far Klein and company have ventured, and not only artistically. They have become a vital part of the local community. Some artists show promise early on and never go beyond that. Dedicated to a vision of theater that embraces ecstasy and provocation — often via whizzbang spectacles whose resonances are simultaneously intellectual, political, and religious — Double Edge Theatre has persevered at premiering imaginative productions that create “a world elsewhere.” There is not much more you can ask. Here’s to 40 more years ….

Also, Double Edge Theatre Company, with its commitment to original works and innovative (to the point of eccentric) stagecraft, stands as a healthy alternative to our theater’s current dependence on the conventional. Today, advertising does the heavy lifting. Boston theaters claim to be programming “bold” work — but most of the selected scripts have first been vetted in New York and its media. Many of these shows have already been staged in or around Broadway or the West End. They also come with ready-made blurbs used to assure ticket buyers of a quality evening. The truth is that New York Times critics can be horribly wrong. Unfortunately, our theater producers are at the reviewers’ mercy when it comes to defining what “bold” theater is. (Who says arts criticism is dead?) Perhaps Boston critics and audiences should stop going for the “bold” and demand independence of mind instead.

As for what “bold” really means, I will turn, as I did in last year’s column, to playwright Dan O’Brien, who offered his useful definition in his book A Story That Happens:

So we listen for what is unspoken in our culture, and it won’t be what our culture wants to hear. But we use our art to make them hear it. They will disagree, because they see things differently; because they don’t know yet how they feel; because they don’t want to feel. The truthful play you write will make you allies and, if you are doing it right, enemies. You will hinder your career by offending those who have risen in their ranks by institutional and commercial rather than artistic acumen.

For me, challenging work deals with “what the culture doesn’t want to hear.” In the spirit of respectful debate, I disagree with my fellow theater critic David Greenham. Diversity has become a pretty routine battle cry. Theatergoers, at least in New England, are all too willing to hear from diverse voices, all too eager to feel good about themselves because they are listening to voices that tell them what they want to hear. Are enemies being made? Potential funders turned off? Or is this about cultivating sunshine allies? It is what is not being talked about — what is being repressed because it is too difficult or frightening or complicated — that is where our theaters should go.

There were not many examples of that nerviness in 2022, at least among the shows I managed to take in. Editing the magazine slows down my intake of theater. Here are a trio of highlights.

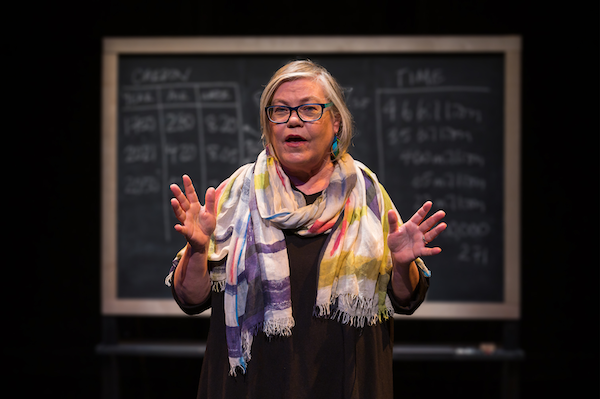

Canadian journalist Alanna Mitchell in a scene from Sea Sick.

Arts Emerson was enterprising enough to bring in Alanna Mitchell’s personable but bracing Sea Sick, a one-woman show in which a Canadian journalist chronicles her investigation into why the oceans are dying, a quest that involved conversations with a number of top-notch scientists. Eventually her research, though it understandably gave her a bad case of the blues, became the book Sea Sick: The Global Ocean in Crisis, which won the Grantham Prize for excellence in environmental journalism. The show taps into the eloquence of an award-winning author: the evening has the merit of patiently and clearly explaining why the oceans have become so toxic, at times via numbers on a blackboard, most memorably when Mitchell drops a stick of chalk into a beaker of vinegar. Put simply, all the carbon dioxide that’s being pumped (in record levels) into the atmosphere is warming up the oceans, a process that inevitably leads to the depletion of oxygen. And, as Mitchell succinctly puts it, no oxygen, no life. (There are an increasing number of dead zones in the oceans, some the size of New Jersey. They will be the size of continents in the future.)

Along those same climate crisis lines, there was WAM Theatre’s staged reading of Amy Berryman’s script The New Galileos, which posited that government and big money interests were silencing climate change scientists (in this case three females) who were uncovering inconvenient realities. If politicians are charged with helping to ameliorate the climate crisis — we are well beyond solving it — then here was a powerful cry to those who care about the planet’s future to see to it that harsh truths are heard. And acted on. A local production of this low-budget play is called for — not sure there will be any takers.

Do we want to hear the attenuated voices of the beleaguered characters of Samuel Beckett? Arts Emerson imported the splendid one-man show On Beckett, in which comic performer Bill Irwin, ace interpreter of the work by the Nobel Laureate, pays homage to the master’s thorny poetic language.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: American Repertory Theater, Bill-Marx, Bob Israel, Carlos Uriona, David Greenham, Double Edge Theate, Double Edge Theatre Company, Joe-Turners-Come-and-Gone, Rites, Sea Sick, Stacy Klein, The Hidden Territories of the Bacchae, The Huntington Theatre Company, The Life of Pi