Theater Review: Bill Irwin’s “On Beckett” — A Splendidly Literate Treat

By Bill Marx

In his virtuoso one-man show, Bill Irwin pays adroit homage to the language and vision of Samuel Beckett.

On Beckett, written and performed by Bill Irwin. Presented by Arts Emerson at the Emerson Paramount Center, Robert J. Orchard Stage, 559 Washington Street, Boston, through October 30.

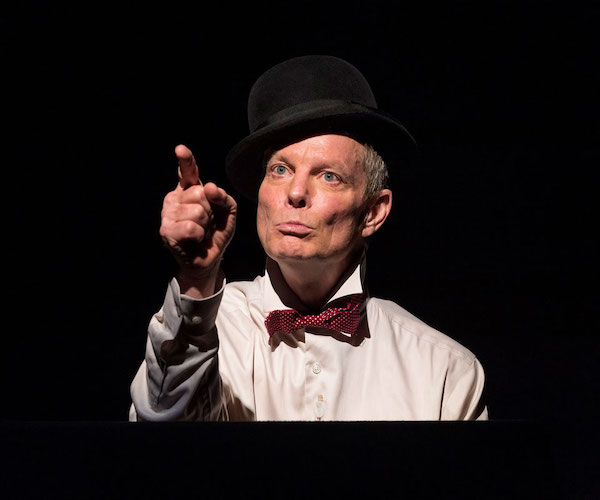

Bill Irwin in On Beckett. Photo by Craig Schwartz

According to Samuel Beckett biographer James Knowlson, in the early ’70s the renowned writer dropped into rehearsals at the BBC for a recording of all of his Texts for Nothing. The reader was actor Patrick Magee, the director Martin Esslin, who recalls:

Beckett sat in the back and said to me: “He’s still doing it too emphatically, it should be no more than a murmur.” So I stopped it and Pat came in and he told him too: “More of a murmur,” until finally the engineer said: “If it becomes any more of a murmur, there’s nothing there.”

Should an author famous for creating characters who are desperate to utter a final word, but can’t, be given the final word when it comes to how performers speak his words? Obviously not. Back in the late ’80s I had the great privilege to hear (at the Museum of Fine Arts) the renowned Beckett whisperer David Warrilow read Ohio Impromptu, That Time, A Piece of Monologue, and the world premiere of Stirrings Still. The actor’s uncannily mellifluous purr — gently steeped in passion — was propelled by a fateful cadence. His magnificent voicings were far from a murmur.

In his splendid one-man show On Beckett, Bill Irwin, another ace interpreter of work by the Nobel Laureate, pays homage to the master’s language. These words often emerge from the lips of attenuated consciousnesses, lost souls riffing, rocking, or stepping along the knife’s edge of oblivion. For me, what’s most important in a performer’s delivery is summed up by actress Lisa Dwan in her 2016 program notes to her evening of Beckett plays (performed at Arts Emerson): “Beckett has shown me that sentimentality isn’t truthful — it is the language of gangsters.” That is the challenge for the oh-so-likeable physical comedian as he delivers brief selections from Beckett’s texts (two from Texts for Nothing) and plays (a chunk of Lucky’s monologue in Waiting for Godot). Interspersed among the performances, Irwin talks about the mystery of the writer’s acerbic vision, and his significance to him as an actor. (He admires Beckett’s use of pronouns, for instance.) Irwin underlines the Irishness of Beckett’s speakers and the early influence of James Joyce, but he comes at these speeches with an American vitality, an energy driven by his belief that Beckett’s speakers may be trapped in some sort of hell but, in their contorted ways, they are struggling to escape, or at least verbally shape, the contours of their prison. Via their tongues, they are treading water. The delusive goal is to either glance at the stars or arrive at the peace of oblivion.

Irwin notes Beckett’s political side, pointing out the writer and his wife’s engagement in the French resistance against fascism in World War II. He points specifically to Pozzo’s tyrannical treatment of Lucky in Waiting for Godot, though that play’s desiccated landscape may well reflect the aftermath of a nuclear war, a barren world that resonates today with the catastrophic effects of climate breakdown. Irwin also makes some provocative points about betrayal in Waiting for Godot, wonders if Beckett’s characters suffer from mental illness, and finds some subtle suggestions of domestic abuse in the prose. He also mentions an online site that juxtaposes lines from Beckett’s work and pictures of cats.

The test for Irwin is to stay away from sentimentality, to not let his enormous skill at baggy pants foolery get in the way of the honesty of Beckett’s poetic angst. The performer admits (too often) that the texts might be difficult for audiences, and he tosses in some interludes of pure clowning to lighten things up. Irwin seems to fear that the writer’s strident truths might be too much for us, and he might well be right. Still, I could have used less business devoted to music hall and more performances of Beckett’s work. I would have loved to have heard Irvin tackle an excerpt from Krapp’s Last Tape or juice up a bit or two from the playwright’s mime skits Act Without Words I and II. Still, the evening is a literate treat, and these are becoming increasingly rare. I agree with the performer that Beckett is no longer stuck in off-off-Broadway productions but, outside of academia, his presence, at least in the theater, is waning. There doesn’t seem much of an appetite for his lyrical explorations of isolation in the musical-crazed/Disneyfied American theater scene, where fantasy and gangsters rule.

Arts Fuse interview with Bill Irwin about On Beckett.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Hmmm. I could never wish for less of Bill Irwin’s clowning. In fact his “baggy pants foolery” struck me as acts of grace that turned the evening around after a slightly flat opening. The problem was that Beckett’s texts for voice that began the show demand a memorable voice above all; and while Irwin is certainly fine vocally, he isn’t at the level of a Warrilow or Whitelaw. Thus he didn’t bring much new or distinctive to the Texts for Nothing or the extracts from the novels. But even now, in his 70’s, his physical grace is astounding – he’s like a vaudeville Ariel (in fact that’s the great role I’d still like to see him do), and it was fascinating to watch his physical evocations of Vladimir and especially Lucky. His insights into what amounts to the climax of Godot were also most welcome – but it was his Lucky (which was saved for last) that made the evening. Watching the poor slave’s body break down along with his mind in Beckett’s famously sputtering monologue, that absurdly professorial attempt to conjure meaning from the universe, was alone worth the price of admission. Irwin didn’t give us the whole speech, but it was still the best Lucky I’ve ever seen. And probably the best I will ever see.

Ironically, Samuel Beckett wished that a voice delivering “Texts for Nothing” should sound as if it was headed toward dissipation – near disappearance. Not the gloriously striking vocals of a Warrilow or Whitelaw. The writer’s intent does not have to be followed, but it does suggest a range of possible approaches. Irwin’s delivery had an interesting energy, a sort of American jitters I found compelling: it was the restless vitality of consciousness caged rather than slowly withering away. I wish there had been more excerpts from the prose. As for the actor’s monumental Lucky, I agree completely. I would have loved the entire monologue rather than detours into sections in which we hear how Irwin’s clown roots keep returning him to Beckett.

I agree that Irvin, in his early seventies, remains a master of physical comedy. But these slapstick routines/gags need time to build, to develop a rhythm. Here we are given bits and fragments as amusing rest stops, I suspect because Irwin — as he says a bit too often — fears that audiences may become uncomfortable with Beckett’s demanding texts. He has a lot of perceptive things to say about the writer from a performer’s perspective, but doesn’t really go into the connections between Beckett’s humor and the severity of his vision of existence.

Thanks for the cogent analysis. Irwin is a great actor who was also involved in the staggering mess of GODOT with the movie stars……

I think the Theater Works premiere of ENOUGH hit the vocal/physical balance in Boston and then when I directed for the International Beckett Festival in Den Hague.