Jazz Album Reviews: From Craft Recordings — DeJohnette, Muhammad, and Spencer

By Michael Ullman

Lost amid a flood of new music in the early ’70s, the three lps under review here never received their due.

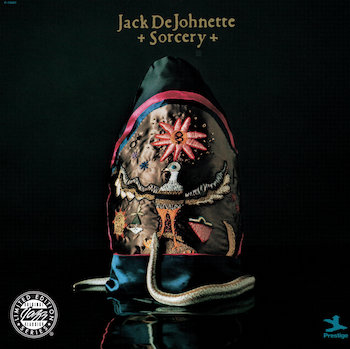

Jack DeJohnette, Sorcery (1974) Craft lp

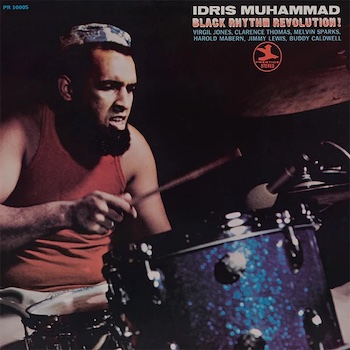

Idris Muhammad, Black Rhythm Revolution! (1970) Craft lp

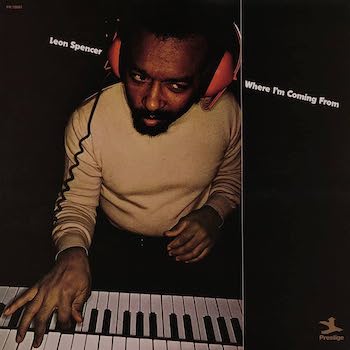

Leon Spencer, Where I’m Coming From (1973) Craft lp

These three sessions were made in a turbulent time in the country’s history and an unsettled time in jazz. For some at the beginning of the decade disaster was in the making. In an unusually intemperate piece in down beat, veteran critic Leonard Feather, distressed by what was then called jazz-rock and by other concessions to commercialism, including Count Basie’s forgettable albums of Beatles’ tunes, called 1970 “the year of the whores.” (By mid-decade, Basie was making an indispensable series of small band records for Pablo — he just had to be asked.) More optimistically, at least by his lights though hardly less realistically, Dan Morgenstern announced that “the castle of rock is beginning to crumble.”

It seemed as if the fate of jazz depended on what was going on in rock. It didn’t turn out that way. The early ’70s saw the emergence as leaders of Herbie Hancock (Headhunters), Chick Corea, and Keith Jarrett, the return to performance of Sonny Rollins (and Earl Hines), the spiritual jazz of Alice Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders, Mingus’s Let My Children Hear Music, and the first flowering of bands from the cooperative AACM (the Art Ensemble of Chicago, the Revolutionary Ensemble). Lost amid this flood of new music, the three lps under review here never received their due. (They remind me of a 1971 tune by Keith Tippett: “Dedicated to You, But You Weren’t Listening.”) In his notes to drummer Idris Muhammad’s Black Rhythm Revolution! (Prestige), reissued, as are the others, expertly mastered on a pristine lp, Bob Porter sounds downright defensive about the rhythm and blues that the New Orleans born drummer plays. “Because of the years and years of brainwashing, it seems difficult to talk of artistry within the concept of Rhythm and Blues,” he wrote in 1971. He need only have waited a few years for Headhunters.

Muhammad’s jazz credentials were solid: he toured with saxophonist Lou Donaldson for three years, recorded with George Benson, Stanley Turrentine, Horace Silver…and Paul Desmond! He was part of the cast of Hair. Nonetheless, the rhythmic revolution he celebrates on Black Rhythm Revolution! is that of James Brown, whose “Super Bad” is a highlight here, the horns (trumpet and sax) riffing behind soloists such as pianist Harold Mabern and guitarist Melvin Sparks. The unquestionalbe highlight of Muhammad’s lp for this listener is the slow blues, “Soulful Drums,” which features the drummer in conversation with the horns. For the most part, the drum feature is a solo over the walking bass (nothing fancy) of Jimmy Lewis. Its hip horn arrangements (by Clarence Thomas) add the necessary variety. “Wander” is a more traditional jazz tune.

Three years later, organist Leon Spencer recorded tunes by Stevie Wonder (“Superstition”), Marvin Gaye (“Trouble Man”), and Curtis Mayfield (“Give Me Your Love”) on Where I’m Coming From with a full horn section including jazz stalwarts such as Frank Wess, on flute and saxophone, and Jon Faddis on trumpet. “Give Me Your Love” is a cheery tune played with characteristic bounce by Spencer, who might as well have been singing. The rhythm section is buoyed by veterans George Duvivier on bass and Grady Tate on drums. They play credible funk on Spencer’s otherwise undistinguished composition “The Price a Po’ Man’s Got to Pay.” (Nice flute solo though.) There’s a mystery here. This is Spencer’s final recording. He seems to have disappeared from the scene directly after making this recording.

Of course, Jack DeJohnette remains a major figure in the music that Spencer may have abandoned. Although he had previously recorded with Jackie McLean, DeJohnette became famous in the mid-’60s with the Charles Lloyd Quartet, which also featured Keith Jarrett. In the late ’60s he was on some of the most celebrated Bill Evans recordings and, of course, he was with the Miles Davis band with Chick Corea.

Sorcery is a gem, with its own surprises. The title tune features a solo by electric guitarist John Abercrombie over the bass lines of another star, Dave Holland. Bennie Maupin, who so enlivened Bitches Brew, also solos on bass clarinet on “Sorcery#1.” It’s followed by “The Right Time.” Given the times, I thought this would be a political statement. It’s a “vocal.” The band yells asynchronously in every way possible the words The time has come. “The time….” someone shouts, and others pop in and out with their versions. Someone later shouts “Open the door.” Then, comically, they seem to lose faith. Is this the time? 8:45? The piece ends with a cymbal crash and the band moves into the funky “The Rock Thing” with a guitar solo by Mick Goodrick.

The longest piece here is “The Reverend King Suite.” It contains a welcome Dave Holland solo. There’s a bit of a mystery here as well. One of the musicians is Michael Fellerman who plays trombone and metaphone, which I know of as a kind of room that has been transformed into an instrument. This seems to be Fellerman’s only recording. DeJohnette plays the wild sounding electric keyboard on the tribute to Dr. King. On this track we hear Fellerman groaning in the lower range of the trombone with Holland playing parallel to him. It’s a somber version of free jazz. The album ends on a cheerier note with DeJohnette’s “Four Levels of Joy” and the equally lighthearted “Epilog.” Sorcery is in particular a welcome reissue, because of the variety of its compositions and for the stellar performances of a nearly all-star band.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Black Rhythm Revolution!, Crafrt Recordings, Idris Muhammad, Jack DeJohnette, Leon Spencer, Sorcery