Jazz Album Review: “Thelonious Monk The Classic Quartet” — Remastered

By Michael Ullman

Thelonious Monk can sound like someone skipping (or even tripping) — and yet the swing is there.

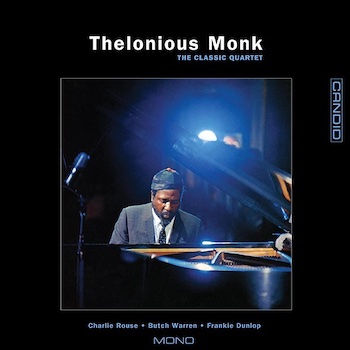

Thelonious Monk The Classic Quartet (Candid)

Play what you want, Thelonious Monk (supposedly) said, and let the world catch up to you. In the spring of 1963, when The Classic Quartet was recorded, the world was catching up to Thelonious Monk. He was signed that year by Columbia Records: he first recorded for them on March 29. On February 28 of the following year, his image appeared on the cover of Time magazine with the banner, “Jazz: Bebop and Beyond.” (Three jazz people had preceded him on that cover: Louis Armstrong, Dave Brubeck, and Duke Ellington. Only Wynton Marsalis has appeared there since.) In the spring of 1963, he took his quartet with tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse, bassist Butch Warren, and drummer Frankie Dunlop on a triumphant tour of Japan where on May 23 he appeared on Japanese television. The Classic Quartet is the monophonic audio portion of that broadcast. (It is not the concert that produced Monk in Tokyo, which was recorded two days earlier.)

Play what you want, Thelonious Monk (supposedly) said, and let the world catch up to you. In the spring of 1963, when The Classic Quartet was recorded, the world was catching up to Thelonious Monk. He was signed that year by Columbia Records: he first recorded for them on March 29. On February 28 of the following year, his image appeared on the cover of Time magazine with the banner, “Jazz: Bebop and Beyond.” (Three jazz people had preceded him on that cover: Louis Armstrong, Dave Brubeck, and Duke Ellington. Only Wynton Marsalis has appeared there since.) In the spring of 1963, he took his quartet with tenor saxophonist Charlie Rouse, bassist Butch Warren, and drummer Frankie Dunlop on a triumphant tour of Japan where on May 23 he appeared on Japanese television. The Classic Quartet is the monophonic audio portion of that broadcast. (It is not the concert that produced Monk in Tokyo, which was recorded two days earlier.)

I am not sure why this group is called “the classic quartet.” I am partial to the Coltrane-Monk band and the one with Johnny Griffin. But this remaster from Candid is exciting for a variety of reasons, including the recorded sound, which has the bass and drums featured more prominently than is typical of the time. The repertoire is familiar: it’s all Monk tunes except for his solo feature, “Just a Gigolo,” which Monk first recorded for Prestige in 1954. The performance begins with the rough-edged “Epistrophy.” Even Monk’s short introduction is distinctive in its percussiveness and unique accenting: he’s one of the rare pianists whom you can identify after a single bar. Charlie Rouse, who first recorded with Monk in 1959, takes the first solo. He does some of what Sonny Rollins calls “pecking,” widely spaced staccato single notes, as if to emphasize the angularity of the piece. Monk solos next, his every line made vital by his subtle timing. One hears in this recording better than in most that Monk is in conversation with the drummer, in this case Frankie Dunlop, but also with bassist Ore.

Thelonious Monk in Brussels in 1963. Photo: YouTube

Numbers like “Epistrophy” and “Evidence” show Monk’s quirky use of more or less complex chord changes. “Evidence” is based on “Just You, Just Me,” but it is thoroughly transformed into a funny-walking original. Rouse solos, sometimes honking or squealing, but mostly his powerful tone plays with the rhythms Monk laid out for him. Monk’s solo is a marvel: he holds notes when one least expects them, uses pauses as expressively as his trills or thumping repeated chords. He can sound like someone skipping (or even tripping) — and yet the swing is there.

The set continues with the marvelously inventive “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are,” which Monk first recorded with Sonny Rollins. He’s a master of simple as well as complicated changes. Who has written a more distinctive version of these time-honored changes than Monk does in his eccentrically titled “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are”? This concert ends with a slow, swaggering version of his most elemental, but no less enticing, blues: “Blue Monk.” It’s been recorded something like 500 times. Monk makes it sound fresh. Although he got his start in the bebop era, he uses no virtuosic flourishes. Stil, every phrase is exquisitely timed, and comes across with Monk’s uniquely percussive, often dissonant, piano sound. “Blue Monk” also leaves room for a walking bass solo and a short solo by drummer Dunlop.

A highlight of this concert, of any Monk concert, is his solo number. Here it’s “Just a Gigolo,” a standard that Louis Armstrong recorded in 1931. It’s hard to describe the appeal of a Monk ballad performance. His hesitations are broken up by emphatic thumps, so it can sound as if he is just learning the piece. Monk seems to be listening to his own playing as if it were someone else’s. Then he will start striding with his left hand. There’s a humorous side to this deconstruction of a standard, but it is also touching. To misuse one of his titles, it’s Monk’s dream we are hearing, something intimate even when it’s blaring.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Monk is the greatest piano player of that day until forever! I have a copy of Art Kane’s photo of almost ALL of the great ones at that time and every time I look at it it still shakes me that just about all those great people are gone! I was lucky to live at that moment!