Film Review: Two Music Docs That Go Deep — “City of a Million Dreams” and “Heaven Stood Still: The Incarnations of Willy DeVille”

By Noah Schaffer

Both of these documentaries offer gratifying viewing for any curious roots music fan.

Black Men of Labor marching and singing “Amazing Grace” during their annual second line parade. Photo: courtesy of City of a Million Dreams.

With major streaming sites cutting way back on their independent documentary offerings, some filmmakers are finding audiences by going back to barnstorming via in-person screenings of their films, often followed by Q&As with the director. Two rewarding examples of this are happening in Boston this month: City of a Million Dreams at the Somerville Theater on June 20 (with a trek to the Martha’s Vineyard Film Society on June 23) and Heaven Stood Still: The Incarnations of Willy DeVille at the Regent in Arlington on June 29. One is a deep dive into a famous but not always properly contextualized regional tradition; the other is more of a conventional biography of an undersung musician. Both efforts offer gratifying viewing for any curious roots music fan.

City of a Million Dreams is far from the first film to look at the New Orleans jazz funeral and Mardi Gras Indian traditions. Pioneering director Les Blank tackled some of the same terrain in 1978’s Always for Pleasure, and there’s currently a streaming PBS offering called Big Chief, Black Hawk.

City of a Million Dreams stands out because it uses both historic photographs and recently filmed reenactments to focus on New Orleans’ colorful and lively street culture traditions, which developed directly out of the Sunday gatherings of slaves in Congo Square. In a particularly revelatory scene, one of the major voices in the film, clarinetist Dr. Michael White, demonstrates the link between the wailing traditional jazz sound and African musical and religious customs.

The doc, which is described as the “sequel” to a book of the same name by filmmaker and journalist Jason Berry, also explores how the “second line” jazz funeral developed out of both African tribal structures and European high society practices. The funerals were mounted by the Black fraternal and social aid organizations to meet the end of life needs of the community during segregation. The sources for the ritual are diverse, drawing on everything from the legacy of Haitian slave revolt refugees to beliefs in the Sicilian immigrant community.

Gregg Stafford and Dr. Michael White performing at Lolis Elis’s funeral. Photo: courtesy of City of a Million Dreams.

“Dancing when someone dies is the most brilliant thing you can do,” observes writer and videographer Deb “Big Red” Cotton, a West Coast transplant who is the other central figure in the film. A newcomer like Cotton may seem to be an unlikely resource in a city known for its multi-generational musical families, but her enthusiasm for learning about the spirit and the source of New Orleans’s Black culture makes her an ideal guide.

Any contemporary story of New Orleans street culture has to deal with how the traditions have remained resilient throughout myriad challenges. Dr. White, whose priceless archives were destroyed by Hurricane Katrina, insists that racism’s tenacious presence makes the second line tradition relevant today. “You are transformed into another world that really sets you free,” he observes. But even those joyous street parades can’t escape the violence in the city, and here the film takes an especially tragic turn. That the doc was completed at all is a miracle worthy of a New Orleans second line celebration. Anyone can enjoy the city’s blaring brass bands, bedazzled Mardi Grad Indians, and struttin’ second line dancers. City of a Million Dreams is required viewing for anyone who wants to learn the culture’s full story.

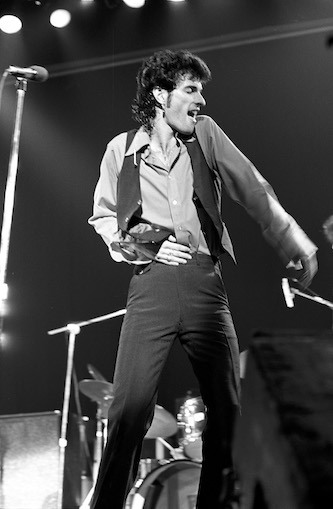

Willy DeVille at the Capitol Theater in Passaic,New Jersey on May 5, 1978. Photo: Ebet Roberts

It’s easy to see why Heaven Stood Still director Larry Locke was enticed by the story of Willy DeVille, who from the ’70s until his death in 2009 sang what today would be called roots rock. DeVille was talented, troubled, and mysterious. The dark and rich stories in his songs and his gravely, soulful voice would seem to have surefire appeal to fans of Bruce Springsteen, Leonard Cohen, or Tom Waits. But, despite scoring a contract with Capitol Records, years of critical praise, and an Oscar nomination (for a song in The Princess Bride), DeVille remained at best a cult favorite in the US.

In one of the several archival interviews stitched together in the doc, DeVille talks about growing up in Stamford, Connecticut “where nothing fuckin’ happens,” dreaming of one day experiencing the swagger, style, and danger he saw acted out in West Side Story and heard on records by the Drifters. (The group’s famous lead, Ben E. King, is among the film’s talking heads.) DeVille escaped what was then a New England factory town and eventually landed in New York right as the punk revolution was pouring out of CBGBs.

DeVille played a Latin-tinged take on straight up rock ‘n roll; the charismatic singer told his yarns over a Bo Diddley beat. Novelist Nick Flynn talks about seeing a DeVille show at Boston’s Paradise Rock Club that was so wild that Flynn and his pals woke up the next morning in a Hyde Park drunk tank.

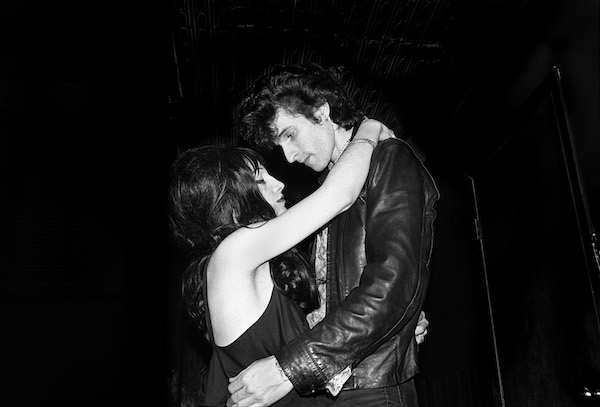

Much of DeVille’s life seems like it could have been plucked out of a Christopher Guest mockumentary about a troubled rocker. There’s the predictable series of intense romantic relations, including some turbulent years with model Toots DeVille. Capitol hopes for a blockbuster commercial rock album; instead, the label is delivered a DeVille recording of elaborately arranged French chanson music, which it refuses to release. Another Boston voice in the film, Peter Wolf, describes the joy he found in DeVille’s music and his anguish at going backstage after a show to find DeVille holding a needle. Eventually DeVille finds redemption with a series of acclaimed albums he makes with the cream of the New Orleans and Mexican-American music worlds. (A Mariachi version of Hendrix’s “Hey Joe” is especially inspired.)

Thanks to those projects, DeVille becomes a bona fide star overseas. But as musical tastes in the US change he becomes even more obscure at home. Wolf mentions that DeVille’s last Boston show at the Middle East barely drew 30 audience members. (To this day Wolf’s pal Dennis Brennan often performs a cover of DeVille’s “Mixed Up, Shook Up Girl.”)

Toots and Willy DeVille backstage at Max’s Kansas City in New York City on January 14,1977. Photo: Duana LeMay

The small number of diehard fans of DeVille’s music will no doubt appreciate the memories and insights served up by DeVille’s musical collaborators. Ironically, these contributions end up taking away valuable screen time from the performances and compositions that make DeVille worthy of such a film in the first place. Still, Heaven Stood Still is worth sticking with: near the end of his too-short life, DeVille, touring in Europe with a small combo, sits down with a DVD director and gives his most lucid interview in the film. Of the Latin pirate character he’s created for the stage, DeVille admits “He’s hard to live with.” The stripped-down musical arrangement of the session pays apt homage to the beauty of DeVille’s vocals and songwriting.

Noah Schaffer is a Boston-based journalist and the co-author of gospel singer Spencer Taylor Jr.’s autobiography A General Becomes a Legend. He also is a correspondent for the Boston Globe and DigBoston, and spent two decades as a reporter and editor at Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly and Worcester Magazine. He has produced a trio of documentaries for public radio’s Afropop Worldwide, and was the researcher and liner notes writer for Take Us Home – Boston Roots Reggae from 1979 to 1988. He is a 2022 Boston Music Award nominee in the music journalism category. In 2022 he co-produced and wrote the liner notes for The Skippy White Story: Boston Soul 1961-1967, which was named one of the top boxed sets of the year by the New York Times.