Opera Album Review: Can Conductors Compose Well? Consider Mahler, Bernstein, and Now Antal Doráti

By Ralph P. Locke

This world-premiere recording of a powerfully compelling opera, based on a play by Jewish philosopher Martin Buber, is revelatory.

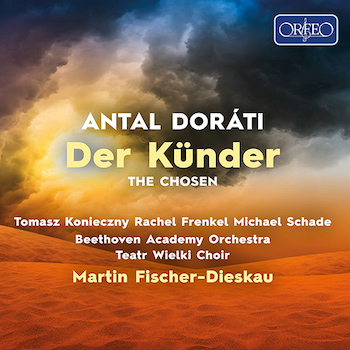

Antal Doráti: Der Künder (The Herald)

Tomasz Konieczny (Elijah), Michael Schade (Ahab), Rachel Frenkel (Jezebel), Ron Silberstein (Elisha), Mi-Young Kim (Tanit), Yuval Oren (her child).

Teatr Wielki Choir Poznań, Beethoven Academy Orchestra, cond. Martin Fischer-Dieskau.

Orfeo 220313 [3 CDs] 161 minutes.

Click here to purchase or to listen to the beginning of any track.

Many first-rate performers also composed; some even started out as composers before focusing instead on a career as singer, instrumentalist, or conductor. Posterity has had to figure out how to value the works of, say, Mahler (best known as a conductor during his lifetime), Joseph Joachim (a great violinist and pedagogue), Pauline Viardot (a contralto who could also act a role superbly, play the piano at a high level, and compose), and Artur Schnabel and Robert Casadesus (internationally renowned pianists). What will future generations say about the operas of conductors Lorin Maazel and Michael Tilson Thomas? Or the uneven, but sometimes brilliant, later works by Leonard Bernstein, including the opera A Quiet Place, the Concerto for Orchestra (“Jubilee Games”), and the song cycle Arias and Barcarolles?

Many first-rate performers also composed; some even started out as composers before focusing instead on a career as singer, instrumentalist, or conductor. Posterity has had to figure out how to value the works of, say, Mahler (best known as a conductor during his lifetime), Joseph Joachim (a great violinist and pedagogue), Pauline Viardot (a contralto who could also act a role superbly, play the piano at a high level, and compose), and Artur Schnabel and Robert Casadesus (internationally renowned pianists). What will future generations say about the operas of conductors Lorin Maazel and Michael Tilson Thomas? Or the uneven, but sometimes brilliant, later works by Leonard Bernstein, including the opera A Quiet Place, the Concerto for Orchestra (“Jubilee Games”), and the song cycle Arias and Barcarolles?

Here we have our first chance at assessing a three-act opera by an equally renowned conductor: Antal Doráti (1906-88). This Hungarian-born maestro was renowned for whipping orchestras into shape in the US (Dallas, Minneapolis, Detroit), England, Sweden, and elsewhere. He made close to 600 recordings, including the complete symphonies of Haydn, the ballets and other major orchestral works of Tchaikovsky, much Bartók, and a persuasively energetic Flying Dutchman starring Leonie Rysanek and George London. He eagerly promoted the works of Luigi Dallapiccola and other then-current composers.

Doráti was born in Budapest to a German-speaking family (his mother’s family was from Graz, Austria; his father’s background was Jewish). I heard him state in a radio interview that he wanted his last name accented on the first syllable, in the manner of most Hungarian words. Sometimes one sees an acute accent on the “a” (as I’ve given it here), but that only indicates how the “a” is pronounced — it does not denote syllabic stress.

Doráti studied composition early on with Zoltán Kodály and Ernst von Dohnányi, then broadened his knowledge by spending two years at the University of Vienna. Throughout his career he composed actively, sometimes for specific performers (notably, in later decades, oboist Heinz Holliger). There have been at least three previous CDs devoted to his works, and others have appeared on CDs of diverse 20th-century chamber works. Like many composer-conductors (Mahler and Bernstein, for sure) Doráti was as eclectic in his compositional style as he was in the repertory that he conducted. This is immediately evident in Der Künder: it is his only opera, a massive three-acter that he completed in 1984 at the age of 76. I was reminded of Bernstein’s symphonies and the aforementioned opera A Quiet Place, so wildly diverse are the stylistic influences, with the important exception that, unlike in those Bernstein works, there is nothing bluesy or jazzy in Doráti’s opera. Perhaps, as some have said about Bernstein, Doráti could not help reproducing gestures and effects from pieces that he had heard, studied, or conducted. I thought I noticed substantial echoes, though never quite quotations, of composers as varied as Debussy (Martyrdom of Saint-Sebastian), Ravel (Boléro, in the beginning of scene 1, after the prologue), Stravinsky (Petrouchka and Les Noces), Britten, Messiaen, and many others. Plus, there sure seems to be some Wagner and Mahler toward the end (as Elijah ascends to Heaven), a passage that is the only platitudinous moment in the work.

Doráti’s basic stylistic orientation here is tonal but with post-Debussyan extensions, such as parallel chords in a mode other than the standard major or minor. The opening of Act 3 is a fugato in a clearly Hungarian-sounding mode (major with raised fourth and lowered seventh). Not surprisingly, the work reveals a remarkable ear for instrumental effects large or small (e.g., a quiet trumpet line under a solo singer). It may be that the various resemblances that I noted earlier merely show Doráti reacting with apt musical expression to each new situation in the text and action, much as other conservative-modern composers (say, Gottfried von Einem or Carlisle Floyd) would have done. Yet somehow each scene and moment (aside from the aforementioned finale) sounds freshly minted.

Doráti fashioned the libretto himself, basing it on numerous passages from Elijah (1951, publ. 1963), a 74-page “mystery-play” by the Vienna-born Jewish philosopher Martin Buber. Buber moved to British-Mandate Palestine in 1938 to escape the Nazi tyranny and became a committed Zionist, but one who insisted on a binational solution for the Jews and Arabs in Palestine. Buber’s play has rarely if ever been staged, though it has been much discussed by Buber scholars.

Antal Dorati, National Symphony Orchestra conductor and music director from 1970 to 1977.

Doráti named his opera Der Künder. In the CD booklet, the two words are translated as “The Chosen,” which is misleading, not least because that phrase could be taken as a plural (“The Chosen Ones”), whereas the German title is clearly in the singular. A closer translation would be “The Prophet” or “The Herald.” In the course of the work, Elijah names Elisha as his successor to announce (verkünden) God’s will to the evil and arrogant King Ahab.

The plot is based largely on events from 1 Kings 12-22: the tales that involve the prophet Elijah, including the scene in which he brings a dead child back to life, and the scene of competition between the followers of Baal and those of Jehovah.

Some of the same stories are portrayed in Mendelssohn’s 1846 oratorio Elijah. But, whereas Mendelssohn’s work ends with strong hints that Elijah’s wonder-working foretells the powers of an even more transformative figure to come (Jesus), Buber and Doráti strictly avoid Christianizing these tales drawn from the Hebrew Bible.

The most imaginative aspect of Doráti’s work is its treatment of the voice of God. Consistent with Buber’s theology about the intimate (“I-Thou”) relationship between an individual and her or his concept of the Divine, Doráti asks that the vocal lines for God always be sung by the singer who plays the character whom God is addressing at that moment. Doráti proposed that, in a live performance, this could be done by having each such singer prerecord God’s statement; the recorded segment would then be transmitted to loudspeakers placed in front of the stage, “where the audience is located.” In the present recording, the individuated voices of God do not seem to come from some other location but, instead, are enhanced by a touch of echo.

There are nine orchestral interludes. Some of these set the scene. Others accompany stage actions — for example, an orgiastic dance for the worshipers of Baal, or a funeral march after the death of the nasty King Ahab. The funeral march perhaps also predicts the event to be heard next: the aged Elijah’s farewell as he leaves this earth in a fiery chariot.

I was surprised to find myself becoming so deeply involved in what, I had feared, might feel distant and abstract. I wonder, in fact, if the work might better be performed as an oratorio: that is, not enacted in costume but done as a semi-staged “in-concert” presentation, with appropriate entrances, exits, and gestures. After all, the Bible text does not provide the details that would be required for substantial onstage action, and Buber’s enrichments lie more in the realms of philosophy and symbolism than in theatrical embodiment and physical movement.

Conductor Martin Fischer-Dieskau.

This is not to say that the work is undramatic! We get to hear (as the oratorio genre readily allows) highly effective statements — invented by Buber — from the mother of the dead boy, the egomaniacal King Ahab and Queen Jezebel (a detestable pair roughly comparable to Richard Strauss’s Herod and Herodias), some peasants, and so on. Perhaps Buber was inspired in part by Thomas Mann’s famous tetralogy of novels from two decades earlier, Joseph and His Brothers, which likewise expanded upon the biblical tales.

Buber also incorporates other thematically relevant texts, such as Job’s famous line “The Lord giveth, the Lord taketh away” and most of the 23rd Psalm.

All in all, I suspect that an imaginative stage director (whether the work is done on stage or in concert), inspired by the work’s text and music, could turn Der Künder into a deeply involving occasion for the eye, ear, and mind. I also wonder if some conductor might make an effective suite out of those highly characterful orchestral interludes.

The performance, by an orchestra based in Kraków (Poland), and with major vocal soloists from Canada, Poland, Israel, Ukraine, and South Korea, seems all that one could possibly want. The Canadian in the cast, tenor Michael Schade, was born in Gelsenkirchen, Germany, and raised in Switzerland. All six singers of the major roles (see header) pronounce the Buber-based text beautifully and meaningfully, never wobbling or ranting. A few singers who each take several minor roles have voices that are unsteady or, it seems, time-frayed, but the passages in which they sing are mercifully brief.

Tenor Schade is renowned for performances as Mozart’s Idomeneo; baritone Tomasz Konieczny is in demand as Wotan; and mezzo Rachel Frenkel has sung such diverse roles as Fenena (in Nabucco) and Wellgunde (in the Ring Cycle).

The conductor, Martin Fischer-Dieskau, is one of three musically talented children of the famous Dietrich F-D. Martin F-D has conducted symphony orchestras and opera companies throughout the world, and his experience shows here in his firm control and his apt adjustments of tempo and orchestral balance.

It surely helps that the work was recorded in a studio, where one can do numerous shortish takes and, if necessary, alter microphone placement to allow each moment to be captured vividly yet in proportion to the whole.

Alas, the long booklet-essay, by the conductor, is poorly organized. Also ineptly translated: “Im Notentext der Oper” does not mean “with the operatic text” but rather something like “in Doráti’s music for the opera.” A synopsis and full libretto are helpfully provided; both are likewise peppered with nonsensical misrenderings. (No translator is named.)

Hearing this opera has made me want to seek out other works by composer-conductor Doráti. And it has made me more curious about the compositions of other composer-conductors and composer-performers. Record companies, to their credit, are helping us in that process.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here by kind permission.

Tagged: Antal Doráti, Der Künder, Martin Fischer-Dieskau, Orfeo, Ralph P. Locke

Where can I find the Martin Buber play in English?