Book Review: “The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams” — The Very Model of a Plain-Spoken Homespun Patriot

By Daniel Lazare

Samuel Adams, a superb political organizer who helped turn the Boston Massacre into a cause célèbre, was more conservative than modern admirers, including biographer Stacy Schiff, want to admit.

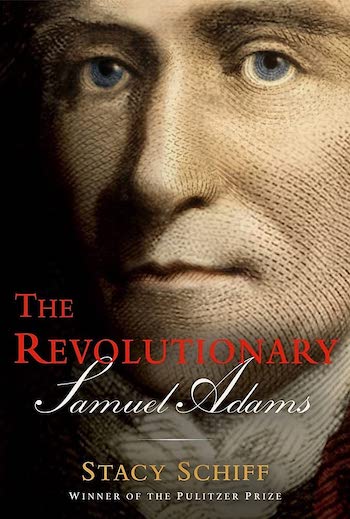

The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams by Stacy Schiff. Little, Brown, 432 pages.

Of the making of books there is no end, especially when it comes to the founding fathers. “Founders chic” began in the mid-1990s when a National Review writer named Richard Brookhiser published a biography of George Washington that shot up the bestseller lists. More titles followed, bios of Alexander Hamilton by Brookhiser and Ron Chernow, a bestselling portrait of Thomas Jefferson by the historian Joseph J. Ellis, David McCullough’s Pulitzer-winning biography of John Adams, and no less than three bios of Franklin — by H.W. Brands, Edmund Morgan, and Walter Isaacson — all between 2000 and 2003.

Of the making of books there is no end, especially when it comes to the founding fathers. “Founders chic” began in the mid-1990s when a National Review writer named Richard Brookhiser published a biography of George Washington that shot up the bestseller lists. More titles followed, bios of Alexander Hamilton by Brookhiser and Ron Chernow, a bestselling portrait of Thomas Jefferson by the historian Joseph J. Ellis, David McCullough’s Pulitzer-winning biography of John Adams, and no less than three bios of Franklin — by H.W. Brands, Edmund Morgan, and Walter Isaacson — all between 2000 and 2003.

Now, some two decades later, we have Stacy Schiff’s new biography of Samuel Adams called, simply enough, The Revolutionary. It’s odd that it took the movement so long to get around to the other Adams because for a time he was the most important of all. He’s the superb political organizer who helped turn the Boston Massacre into a cause célèbre. Without him, there would have been no Boston Tea Party, no “shot heard round the world” at Lexington and Concord, and no Declaration of Independence — which he signed, by the way. The revolutionary process would last for nearly a quarter of a century, from the revolt against the Sugar Act in 1764 to the ratification of the Constitution in 1788, but there’s no question that Samuel Adams was the dominant figure for the first half. Indeed, when his cousin John arrived in Versailles as America’s first ambassador to France in 1777, faces fell when locals realized that he was the wrong Adams. Samuel was the model of a plain-spoken homespun patriot. He was the Adams that everyone wanted to see.

Schiff, the author of a history of the Salem witch trials and a biography of Cleopatra, does a good job of explaining what made Adams so extraordinary. Following graduation from Harvard in 1743, he spent his first years adrift. He found work with a prominent local merchant, but it didn’t work out. His father gave him a thousand pounds to start a business, but he ran through the money with nothing to show of it. He eventually landed a post as a market inspector, which paid him a modest salary and allowed him to mingle with bakers, butchers, and oystermen. This was more to his liking. But he only found his real calling in 1747 when Boston exploded over efforts by a British admiral to forcibly recruit sailors along the waterfront to replace a crew that had deserted. “Impressment” may have been standard practice in Britain, but it was not in America. Bricks flew as mobs rampaged through the streets. When the royal governor, an army officer named William Shirley, called out the militia to restore order, he found “that the mob and the militia — officially every man between the ages of sixteen and sixty — were one and the same,” as Schiff puts it. Boston was a turbulent place long before independence was an issue.

Adams was relentless. He cared little for money and was so frugal that he bragged he could live on a turnip. As his first boss said, “his whole soul was engrossed by politics.” A few months after the impressment riots, he and a group of friends started a newspaper that “offered a steady stream of excerpts from [John] Locke and attacks on the royal governor; a smattering of foreign news, headlines from New York and Philadelphia, occasional verse, and plenty of local color.” Adams filled the paper with odes to freedom. “There is no one thing which mankind are more passionately fond of, which they fight with more zeal for, which they possess with more anxious jealousy and fear of losing, than liberty,” he wrote. Adopting the guise of a poor cobbler, he argued that the opinions of “the less artless” mattered just as much as those of “the great and affluent.” He pitied the man “whose soul is enslaved to the passion of ambition — whose life and happiness dependent on the breath or nod of another.” Schiff notes that Adams’s honest and unlettered cobbler “quoted liberally from Tacitus, Cicero, and Milton.”

If The Revolutionary were a bit less narrowly focused, it would have made clear that Adams was not the only one going on in this fashion. To the contrary, rhetoric like this was a classic expression of Old Whig or Country ideology, a school of thought that was a minority current in England but dominant on the other side of the Atlantic. A reaction to growing wealth and centralization, it stressed freedom, independence, and rough-hewn republicanism over the foppery, avarice, and corruption of the royal court — not that of the king so much as the advisers and hangers-on around him. The movement’s heroes were Locke and Milton; its Bible was “Cato’s Letters,” a collection of essays by journalists John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon published in the 1720s that would be required reading in the colonies for the next half-century.

Power is “like fire,” Trenchard and Gordon warned; “it warms, scorches, or destroys according as it is watched, provoked, or increased.” Since power was dangerous, the less “patriots” granted to the central authorities, the freer they would be. This was an ideology of anti-authoritarianism that “snuff[ed] the approach of tyranny in every tainted breeze,” to quote Edmund Burke.

But there was a hitch. If centralized power was bad, what did Old Whigs want to replace it with — endless decentralization? How could old-fashioned republicanism be the answer in a fast-changing world?

Those questions are key to why the first half of Adams’s political career took off and why the second petered out so unsatisfactorily. Adams emerged in the 1750s as a leader of the Boston Caucus, a behind-the-scenes club or cabal that his grandfather, Deacon Adams, had helped found in 1719. The caucus, which set the agenda for the Boston town meeting, the city’s ostensible government, was populist, Old Whig, and perennially at odds with the royal authorities. When the debt-strapped British set off to tax the colonies in the wake of the Seven Years’ War of 1756-63, patriots in and around the caucus swung into action behind a slogan of “no taxation without representation.” Although a Parliament dominated by the landed aristocracy claimed a right to legislate on behalf of Britons on both sides of the ocean, Adams laughed the idea off. Americans, he said, “can no more be judged of by any member of Parliament than if they lived in the moon.” Adams was not yet an independista, but was plainly heading in that direction.

Samuel Adams — why did the first half of his political career take off and the second peter out so unsatisfactorily?

The 1764 Sugar Act raised the old conflict to new heights. For the British, the problem was simple. Smuggling was rampant because earlier legislation had set import taxes too high. So why not lower taxes while stepping up enforcement? Everyone would benefit, law-abiding shippers and merchants no less than royal officials eager to see revenue go up. But Adams disagreed. Allowing Britain to tax the colonists at will meant reducing them from “free subjects to the miserable state of tributary slaves.” If the first principle of British liberty was self-rule, self-taxation was second.

According to James Otis, another member of the Boston Caucus, the controversy “set people a-thinking in six months more than they had done in their whole lives before.” The Stamp Act followed in 1765, a requirement that every will, deed, or other legal document be printed on specially embossed paper made in London and that newspapers carry a stamp as well. This was a serious blow to a Boston-based publishing network that was rapidly spreading throughout America. This time, Boston did not erupt on its own — other colonies joined in, Virginia most notably. A curious alliance was taking shape between freedom-mad New Englanders and southern slave-owners.

The cauldron continued bubbling for the next decade, and Adams was ubiquitous throughout, dashing off articles, putting together committees of correspondence, organizing boycotts, and so on. A member of the Continental Congress, he seconded his cousin John’s motion to name Washington commander-in-chief of the new continental army. In keeping with his Old Whig ideology, he was a strong supporter of the 1781 Articles of Confederation, a first stab at a national union that, unfortunately, resulted in a federal government so weak that it could barely stand on its own feet.

Trade wars were breaking between the states, conflict with native Americans was erupting along the western frontier, and Revolutionary War debts were going unpaid. Still, centralized power was inevitably bad in Adams’s eyes, so he was at a loss when mounting dissatisfaction led to a constitutional convention in Philadelphia in 1787. “I meet with a national government instead of a federal union of sovereign states,” he complained when the framers unveiled the results. Adams took part in the Massachusetts ratification convention a few months later, but remained silent throughout. He voted for the new plan of government in the end. But his lack of enthusiasm did not sit well with his former artisan supporters, who backed the proposed new constitution to the hilt. Adams’s popularity plunged.

Schiff rushes through this uncomfortable denouement and shortchanges other aspects of Adams’s career that were less pleasant as well. She writes that Adams was repulsed by slavery and that, when his in-laws made him a present of a slave woman named Surrey on the occasion of his marriage, he insisted on setting her free. This is true enough. But what Schiff doesn’t mention is that, in order to keep peace with the Virginians, Adams made sure to keep news of a burgeoning New England antislavery movement out of the Boston Gazette, the newspaper he edited. She describes how a Scottish merchant named John Mein aroused Adams’s wrath by refusing to support an anti-British boycott. But she doesn’t mention that one of the things that got Mein in trouble was an antislavery article he published in a rival newspaper. Abolitionism was not a topic that patriots were eager to see raised. As a member of the Continental Congress, Adams agreed that “free negroes” should not be allowed to enlist in the Continental Army.

Adams was more conservative than modern admirers want to admit. A die-hard Puritan, he believed that theater should be banned on the grounds that it was injurious to public moral health. The new state constitution that he helped create in 1779-80 actually raised property requirements for voting above pre-Revolutionary levels. He opposed efforts to modernize Boston’s municipal government and favored sticking with the time-honored town-council model instead.

These are paradoxes that historians like Patricia Bradley, John K. Alexander, and Ira Stoll have explored. But Schiff believes such things should go unmentioned. Evidently, history is more troublesome and contradictory than she would like.

Daniel Lazare is the author of The Frozen Republic and other books about the US Constitution and US policy. He has written for a wide variety of publications including Harper’s and the London Review of Books. He currently writes regularly for the Weekly Worker, a socialist newspaper in London.

Tagged: American history, American revolution, Samuel Adams, Stacy Schiff