Arts Feature: Recommended Books, 2022

Compiled by Bill Marx

An eclectic round-up of the favorite books of the year from our critics.

Roberta Silman

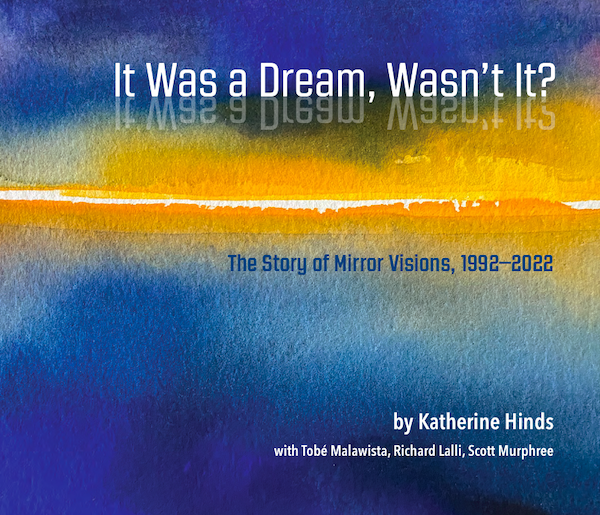

It Was a Dream, Wasn’t It?: The Story of Mirror Visions, 1992-2022 by Katherine Hinds. A beautiful book about how a vision comes into being, starting with Tobe Malawista, Richard Lalli and Scott Murphree, and survives with the help of poets and composers like Boston’s own Scott Wheeler. It tells the 30-year story of a unique musical art-song group that has created new music (scores of commissioned work) to pour out into the world. The authors talked to dozens of smart, fun, creative, brilliant, generous people who are doing what they love. It’s about more than music — it’s the story of love, loss, creativity, determination, the power of art, and the human spirit. Anyone who’s curious about or involved in creative endeavors will find comfort, advice, wisdom, and humor in the story of the Mirror Visions Ensemble. Books are available at mirrorvisionsensemble.org .

Small Things Like These and Foster by Claire Keegan (Grove). Two small, exquisite stories about life in modern Ireland by a master of her craft.

Letters to Camondo by Edmund De Waal (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). A meditation on the tragic Sephardic Jewish Camondo family told through the objects they prized so much. You may remember De Waal as the author of The Hare With the Amber Eyes. This book is equally entrancing, and even more original.

Israeli writer A.B. Yehoshua died this year at 85. I would recommend any of his books, especially A Late Divorce, The Lover, and Journey to The End of the Millennium. He was an amazing writer and his portraits of women are especially good.

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens. Yes, I know you read it years and years ago, but it is still marvelous — Virginia Woolf’s favorite Dickens, and Dickens’s favorite among his books — and well worth a second look, especially since Barbara Kingsolver has written an update, which I plan to review very soon, called Demon Copperhead.

The Hours by Michael Cunningham (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). An opera based on this splendid novel, which won the Pulitzer Prize, has just been launched at the Metropolitan Opera. Even if you don’t plan to go to the opera performance, this is a wonderful book that will enlarge your vision of what a novel can do.

The Grass Harp by Truman Capote, Random House. Published in 1951 when Capote was only 26, this is a marvelous piece of American prose about a lonely young boy in Alabama and his bonds with the women who raise him. Better than I remembered, and that is saying a lot.

Beyond the Bedroom Wall by Larry Woiwode (FSG). The masterpiece of the American writer who died at 80 last year. Much of this novel was published in the New Yorker and made Woiwode famous, for the proverbial 15 minutes. His earlier book is also wonderful and called What I Am Going to Do, I Think. A master at unraveling family relationships, Woiwode gives us a picture of rural America that will stay etched in your mind forever.

Hilary Mantel was a great writer even before her breakthrough book Wolf Hall. For those interested, I loved and read her memoir Giving up the Ghost and her novel set in Africa, A Change of Climate. People tell me that A Place of Greater Safety is also wonderful, and I am planning to look at it and perhaps review it in the future.

Preston Gralla

10 Best Novels of 2022

It’s good to see the backside of 2022, which brought us another year of Covid, Russia’s launching of a brutal, punishing World War II–style war, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and Trump announcing another run at the presidency.

Luckily, though, it was a good year for literature, a place to find solace, entertainment and truth. Whether you’re looking for something light, dark, or in between, something timeless, topical, or both, there’s something for you in these picks of my 10 favorite novels of the year.

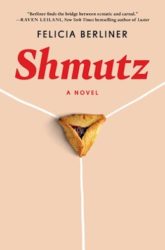

Shmutz by Felicia Berliner

A young, unmarried Hasidic woman becomes addicted to Internet porn. Mishegoss ensues.

Companion Piece by Ali Smith

One of our greatest novelists takes on a post-Brexit Britain struggling against Covid in this strange, moving, unsettling novel.

Grey Bees by Andrey Kurkov

A gentle Ukrainian beekeeper sets out with his hives to find well-tended fields and orchards for his bees to gather nectar so they can survive amidst Russia’s war against Ukraine in 2014. The novel shows the price paid by Ukraine’s noncombatant civilians, in sometimes oblique ways.

Mr. Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe

This funny, bittersweet novel portrays the great American film director Billy Wilder on the downside of his career.

Mercury Pictures Presents by Anthony Marra

This cutting novel about an imaginary film studio in 1941 could have been written by Billy Wilder if he had been a novelist. Humorous, heartfelt, and much deeper than you would expect from its easy-to-read prose.

Mercy Street by Jennifer Haig

A prescient novel published before the overturning of Roe v. Wade that portrays life inside and outside a Boston abortion clinic. It’s full of wit humanity, pain, joy and everything in between.

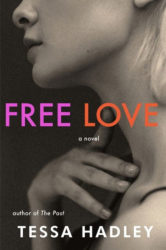

Free Love by Tessa Hadley

A 40-year-old married woman leaves her husband and child to discover love and sex with a younger man in London in the late ’60s. Don’t expect tired cliches about swinging London — it’s achingly felt and captures all of the possibilities and painful chaos of that decade.

Lessons by Ian McEwan

McEwan typically packs a lot into compact novels — and he packs even more into this nearly 450-page one. It’s a kaleidoscopic story of a person and an era, beginning in the late 1950s and into the present when a young boy is seduced by his piano teacher and faces consequences he never quite accepts.

Less Is Lost by Andrew Sean Greer

This follow-up to Greer’s Pulitzer Prize-winning comic novel Less finds the gay novelist Arthur Less forced to hit the road on a book tour thanks to a personal financial crisis. No one compares to Greer for turning bad news into good fun.

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

A novel about three students at Harvard and MIT who create a PC gaming colossus may sound like it’s only for those addicted to video games. But it’s not. Even if you have no idea what a first-person shooter is, you’ll want to read it. It’s about the act and pain of creation and the compromises that need to be made when juggling art with commerce.

Ed Meek

Nonfiction

Race for Tomorrow by Simon Mundy. Mundy, a journalist, travels all over the world, from Greenland to South America, from Siberia to Africa, to look at the effects of climate change and talk to locals on all sides of the political spectrum. To get a grounded and ground-level view of exactly what is happening to our planet, read this book.

Race for Tomorrow by Simon Mundy. Mundy, a journalist, travels all over the world, from Greenland to South America, from Siberia to Africa, to look at the effects of climate change and talk to locals on all sides of the political spectrum. To get a grounded and ground-level view of exactly what is happening to our planet, read this book.

To Govern the Globe by Alfred W. McCoy. To better understand what is going on in the world these days, as well as how we got here and where we are headed, it’s hard to find a better source than McCoy’s new book that traces the rise and fall of empires over the last 800 years, leading up to the current conflicts between the United States, China, and Russia.

Matt Hanson

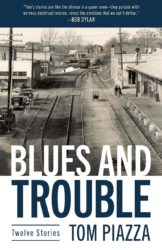

Tom Piazza’s short story collection Blues and Trouble was rereleased this year, 10 years after it was first published. Piazza has written extensively about American music, especially the blues — he won a Grammy for music writing for the liner notes to Martin Scorsese’s blues documentary. I like the title’s reference to what I think is a Robert Johnson lyric — that “trouble” doesn’t tell you right away what it means but warns you just the same. Piazza’s eye for Hemingwayesque minimalism mixed with bluesy tragicomedy serves these characters well; we’re not always sure what exactly is aching inside of them as we follow them on their anxious, unexplained journeys across a crumbling America. The standout is a brilliantly plotless, characterless, genreless piece of writing “about” the great blues shouter Charlie Patton, a vivid meditation on the obscure but haunting images his spellbinding voice conjures up from the depths of the American roil.

Tom Piazza’s short story collection Blues and Trouble was rereleased this year, 10 years after it was first published. Piazza has written extensively about American music, especially the blues — he won a Grammy for music writing for the liner notes to Martin Scorsese’s blues documentary. I like the title’s reference to what I think is a Robert Johnson lyric — that “trouble” doesn’t tell you right away what it means but warns you just the same. Piazza’s eye for Hemingwayesque minimalism mixed with bluesy tragicomedy serves these characters well; we’re not always sure what exactly is aching inside of them as we follow them on their anxious, unexplained journeys across a crumbling America. The standout is a brilliantly plotless, characterless, genreless piece of writing “about” the great blues shouter Charlie Patton, a vivid meditation on the obscure but haunting images his spellbinding voice conjures up from the depths of the American roil.

Drew Hart (*your ‘faithful correspondent’ in Santa Barbara, California)

2022 IN (VERY!) GOOD BOOKS

Along with the largely enjoyable fortune of being able to occasionally review books for the Fuse, I am happy to report that so many of them turned out to be successes this year. Is it because your F.C.* only selects the very special? Could be part of it, but not likely: you can never be sure what you’re diving into in the literary seas! Anyway, nice problem to have had; here’s to 2023…

Standouts among those read:

Mecca by Susan Straight (FSG). People with strong feelings for southern California will be especially rewarded by this striking portrait of the region, which drills down and seeks out the workaday lives of its unsung majority. Nurses, cops, migrants — all are interwoven in a nearly epic, complex tale.

Nobody Gets Out Alive by Leigh Newman (Scribner). That this collection of stories was long-listed for the National Book Award comes as no surprise here. It’s a riveting look at life in Alaska over the past century, peering into corners scarcely ever noticed in the lower 48 — both cash-flush and hardscrabble, urban and wild.

What Just Happened by Charles Finch (Knopf). Actually published in late 2021 and overlooked at first, this nonfiction offering must be included, as we continue to reel from the shock of Covid. It’s one man’s astute, deeply felt account of his own self-quarantined life in Los Angeles during the epidemic, a chronicle of an era that has changed the world, perhaps forever.

Kick the Latch by Kathryn Scanlan (New Directions). A short, super-intense look at the life of a horsewoman on the gritty, small-time, Midwestern racing circuit. The novel is written with lapidary care, and is a great achievement.

Bill Marx

A trio of my favorite books published in the past year.

All who relish the Bard will be delighted by stage director Stephen Unwin’s terrific book Poor Naked Wretches: Shakespeare’s Working People (Reaktion). For my money, the volume should be made required reading for all the directors (in Boston and elsewhere) who routinely patronize Shakespeare’s proletarian characters, treating them as dumb clowns, only fit for “comic relief.” This study makes a convincing case that the Bard’s concern for the lower classes is essential to how he sees the world, and that his radical sensitivity to political injustice is closer in spirit to the iconoclasm of Bertolt Brecht and Karl Marx than many critics will admit. The Bard is certainly more understanding of, and sympathetic to, the plight of the poor than what could be gleaned from most contemporary stage versions, where the marginal players are disposed of with impatient or farcical dispatch.

All who relish the Bard will be delighted by stage director Stephen Unwin’s terrific book Poor Naked Wretches: Shakespeare’s Working People (Reaktion). For my money, the volume should be made required reading for all the directors (in Boston and elsewhere) who routinely patronize Shakespeare’s proletarian characters, treating them as dumb clowns, only fit for “comic relief.” This study makes a convincing case that the Bard’s concern for the lower classes is essential to how he sees the world, and that his radical sensitivity to political injustice is closer in spirit to the iconoclasm of Bertolt Brecht and Karl Marx than many critics will admit. The Bard is certainly more understanding of, and sympathetic to, the plight of the poor than what could be gleaned from most contemporary stage versions, where the marginal players are disposed of with impatient or farcical dispatch.

Ben Davis’s incisive Art in the After-Culture: Capitalist Crisis & Cultural Strategy (Haymarket Books) is the best critical work I have read recently on how artists are dealing with the various social/political emergencies that beset us. Art’s self-image is taking a deserved beating, at least from progressive critics, who are charging that culture — high, low, and in between — is complicit with political and commercial efforts to maintain oligarchic business as usual, even though the future promises to be anything but.

Ben Davis’s incisive Art in the After-Culture: Capitalist Crisis & Cultural Strategy (Haymarket Books) is the best critical work I have read recently on how artists are dealing with the various social/political emergencies that beset us. Art’s self-image is taking a deserved beating, at least from progressive critics, who are charging that culture — high, low, and in between — is complicit with political and commercial efforts to maintain oligarchic business as usual, even though the future promises to be anything but.

All too often, artistic postures of protest are no more than bad faith efforts to defuse anxiety. The strategic goal is to pacify self-satisfied consumers rather than activate citizens, to project a comfortable status quo into the future, regardless of challenging evolving realities. For example, here is Davis on how the eco-friendly rhetoric spouted by the creative class serves as a kind of “status marker” for affluent and educated audiences:

The task isn’t telling people that climate change exists but mobilizing the large number of people who are aware of climate change but feel disengaged or disempowered. One may even suspect that a defanged rhetoric of sponsoring “awareness” becomes the funder-friendly way to avoid promoting interventions, artistic and otherwise, that may say anything too concrete about what must be done.

Against this, Davis argues that it is important to keep in mind the modest but significant way art can help reinforce “a movement perspective outside of itself.” He advises that we not “let navel-gazing guilty consciousness about art’s contradictory social position enter the conversation in a way that takes away from whatever practical support it actually can provide for nascent movements.” In terms of Climate Change, that means artists will increasingly be called on to provide an “imaginative depth that will make images and narratives useful as popular symbols [that] depend on the actual forces battling for a better potential future.”

Naomi Klein insists that “there are no non-radical solutions left.” In the face of mounting cynicism and nihilism, art will invest much-needed value in the present once it dares to imagine positive transformational futures.

The arrival of the first full-length biography of the sui generis novelist, playwright, short story writer, and poet James Purdy (1914-2009) is long overdue and welcome, but James Purdy: Life of a Contrarian Writer (Oxford University Press) would have benefited from more analysis of Purdy’s dangerous brilliance (he excelled in the Melvillian mode, writing ferociously against the American grain) and less attention to his feuds with the New York literary establishment and others, from supporters such as Susan Sontag to frenemies, Edward Albee among them. Granted, Purdy’s waspish temperament never let up over the decades of his career. His perennial disgruntlement, provoked by a lack of mainstream recognition, explains why a writer of his prescient power — he explored gender liquidity well before it became fashionable — is so little known today, even with the support of such charismatic admirers as John Waters:

The arrival of the first full-length biography of the sui generis novelist, playwright, short story writer, and poet James Purdy (1914-2009) is long overdue and welcome, but James Purdy: Life of a Contrarian Writer (Oxford University Press) would have benefited from more analysis of Purdy’s dangerous brilliance (he excelled in the Melvillian mode, writing ferociously against the American grain) and less attention to his feuds with the New York literary establishment and others, from supporters such as Susan Sontag to frenemies, Edward Albee among them. Granted, Purdy’s waspish temperament never let up over the decades of his career. His perennial disgruntlement, provoked by a lack of mainstream recognition, explains why a writer of his prescient power — he explored gender liquidity well before it became fashionable — is so little known today, even with the support of such charismatic admirers as John Waters:

James Purdy I really, really, really like. I have every book he ever wrote. There’s a new one out now (1989) that’s only available in England, Out With the Stars, and it’s in the style of his old really crazy ones. Even gay audiences don’t like him. He’s not exactly politically correct. What he is is over the top. My personal favorite is The House of the Solitary Maggot, but On Glory’s Course is up there. People are so horrible in this book. There’s so much gossip in this little town that while this woman’s hanging her wash out she hears evil things being said about her in the wind. One of the meanest things I’ve ever read is a scene where this daughter, who’s twelve years old, comes to her mother and says, what’s this? She’s having her period. And her mother says, I don’t know. I’ve never heard about this. I think you’re the only person this has ever happened to. So mean. I really like James Purdy. I think he’s great.

“I am not a gay writer, I’m a monster,” Purdy proudly declared. Biographer Michael Synder details the writer’s enormous appetite for ridiculing others — insults sometimes triggered by gay-baiting among the literati. Where the study falls short is explaining why a writer who was so fascinated with the possibilities for love — of all kinds — was so addicted to self-destructive vituperation.

In 2005, Jonathan Franzen nominated Eustace Chisholm and the Works for the Clifton Fadiman Award for Excellence in Fiction, a prize dedicated to recognizing neglected fiction. At the time, Franzen declared Purdy “has been and continues to be one of the most undervalued and underread writers in America.” He insisted that Eustace Chisholm is “so good that almost any novel you read immediately after it will seem at least a little bit posturing, or dishonest, or self-admiring, in comparison.” Hyperbolic, but Franzen has a point — Purdy is an unruly American Master who will never make PBS’s field of polite sacred cows, even though he deserves to be considered in the same league as Saul Bellow and Elizabeth Bishop. The problem is that Purdy is more honest (and less hapless) about the grotesquerie of sexuality than either of them.

Some of Purdy’s novels and short stories hold up splendidly. After I finished the biography I reread Malcolm (an intimidating masterpiece), The Nephew (a delicately acidic vision of Middle America favored by William Carlos Williams), and Eustace Chisholm and the Works (a fierce saga of self-hatred and homophobia that includes a horrific scene of a back alley abortion). I am reading On Glory’s Course now, and Waters is right — it contains episodes of satiric zest worthy of Sinclair Lewis.

Tagged: Bill-Marx, Drew Hart, Ed Meek, Matt Hanson, Preston Gralla