Book Review: “Folk Music — A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs”

By Daniel Gewertz

At points Greil Marcus’s digressive style can seem like nervy brilliance, at others, idle whimsy. What ennobles the book is the critic’s love for his underlying subject: the soulful search for a truer America.

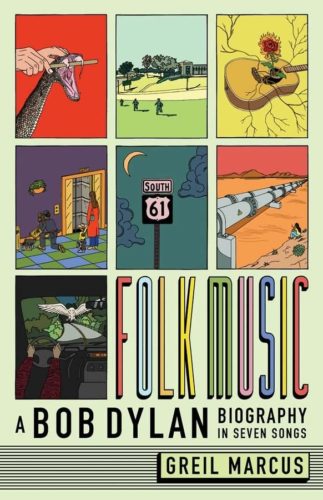

Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs, by Greil Marcus. Yale University Press, 288 pages.

Of Greil Marcus’s 19 books, four now focus on Bob Dylan. About the esteemed critic’s new one, there is much to say. But let us begin with what this book is not about. Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs is certainly not a biography of Bob Dylan. A couple of the chapters treat Dylan as a mere bystander in the author’s free-form thought-journeys; moreover, the discussions of the songs are virtually never tied to events in the artist’s life. Nor are the songs themselves consistently paramount. In the chapter called “Jim Jones,” it takes 36 pages before Marcus even mentions the traditional folk song of that title. The chapter on “Desolation Row” barely mentions the 1965 masterpiece; instead, this short, fascinating commentary takes off on the song’s first phrase — “they’re selling postcards of the hanging” — to ruminate on early 20th-century hangings as festive social occasions. What is assumed to be a satiric Dylanesque image is actually a shameful artifact of American life: public hangings were commonly celebrated with picture postcards for sale.

Of Greil Marcus’s 19 books, four now focus on Bob Dylan. About the esteemed critic’s new one, there is much to say. But let us begin with what this book is not about. Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs is certainly not a biography of Bob Dylan. A couple of the chapters treat Dylan as a mere bystander in the author’s free-form thought-journeys; moreover, the discussions of the songs are virtually never tied to events in the artist’s life. Nor are the songs themselves consistently paramount. In the chapter called “Jim Jones,” it takes 36 pages before Marcus even mentions the traditional folk song of that title. The chapter on “Desolation Row” barely mentions the 1965 masterpiece; instead, this short, fascinating commentary takes off on the song’s first phrase — “they’re selling postcards of the hanging” — to ruminate on early 20th-century hangings as festive social occasions. What is assumed to be a satiric Dylanesque image is actually a shameful artifact of American life: public hangings were commonly celebrated with picture postcards for sale.

The book is rich in musical sources: a long lifetime of them.

Yet the title Folk Music suggests a wider study than what Marcus delivers. The book’s focus is squarely on the 1960s revivalists. Yet even here, Marcus hardly touches upon Dylan’s many songwriter peers — the young, urban composers who grounded their creativity in old-time music.

One has to ask: Is the prominence of Dylan’s name in the subtitle an attempt to bolster sales, or is it a byproduct of Marcus’s stylistic adoration of indirection? Maybe it serves as a mental guideline for the critic, a gambit to give shape to the book’s meandering, sporadically ecstatic prose.

Marcus roams around a subject like some intellectual alley cat, pouncing on a stray idea, idly poking at it, sometimes shaking it in his maw for a vigorous spell. Many of these elaborately unspooled thought-streams are worth the effort, reaching states of grace. But even if an idea fails to come to cogent fruition, Marcus still mounts a flurry of words. Marcus is now 77, but his style sometimes still reflects the excess of a young writer, hypothesizing less by conceptual reasoning than by pumped-up poetic pulchritude, or plain repetition. As in his past writings, Marcus doesn’t just dissect a pop star’s mythological allure. He promotes it. Extends it. In a sense, Marcus might even long to be the literary commentator cum cosmic pop star.

The writer made his reputation as the wildly brainy intellectual of pop music journalism, first in the pages of Rolling Stone, and then most indelibly with his influential 1989 book Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century. Linking punk rock and classical philosophy was one of Marcus’s many audacious moves. Seventeen books later, what still stitches his myriad ideas together is a belief that pop is a resolute touchstone to the wider world. While titled Folk Music, there is little evidence of interest in the wider scope of folk. His focus is, specifically, the old-time rural music of the 1920s and ’30s masters, and most especially, those old-time musician’s most obsessed ’60s acolytes — the songs of “the old weird America” (to quote the title of Marcus’s first Dylan book). Marcus relishes their mythic appeal. Odd, abstruse connections are his inner light as a writer: often the odder the better. Despite his excesses, Marcus ably captures the haunting power of the music of this lost, “real” America.

His use of the term “folk music” might be close to the art-gallery sales slogan “folk art.” The phrase generally means art work that is primitive, unschooled and, not infrequently, tied to mental illness. What interests Marcus most, other than Dylan, are the minor, shadowy figures — several ’60s phantoms the writer resurrects lovingly — the doomed, drug addicted, and alcoholic young singers on the outer edges of the scene, such as the crazed Okie Karen Dalton and Britain’s antisocial Anne Briggs. These women come off as tragic, dissolute characters straight out of a 300-year-old folk song. His writing reaches a poetic peak in its description of Dalton desperately searching for a “good vein” while shooting up in bathrooms before a gig. But it is also a grotesque anecdote. It reveals Marcus’s macabre attraction to those who die for art. Or to art as death. It is convenient that no decently recorded work exists of Dalton from her short prime, so the soul-drenched intensity described here can’t be countered by evidence. (Marcus claims Dalton was twice divorced, with babies, by 17, but Wikipedia puts her age then at 21.)

Marcus is also attracted to the true tale of an old hermitlike mountain fiddler, Lost John, the “moon faced” toothless product of incest: “He and his wife were brother and sister as their parents were.” Captured in a 57 year-old documentary film, the fiddler plays and “the music darkens and lifts so high all sense of reality falls away: this can’t be happening.” Marcus’s rhapsodic spree of words goes on. It is his favorite thing: “the uncanny creeps back.” He definitely has a talent for the creepy, the invisible, the vaporous, the margins of magic. But at points it feels as if the canny journalist has disappeared completely in his enthusiasm. At his essence, he seems to be saying that what cannot be seen or proven is what is most real. At their most possessed, his cascades of words tumble out like the muttered prayers of a spiritual fanatic.

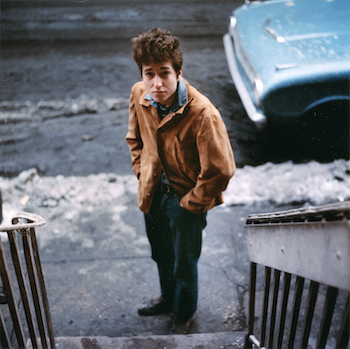

Bob Dylan in 1963. Photo: Don Hunstein

To be fair, Marcus’s fascination with the tortured lives of the drug addled may not rest on a voyeuristic interest in self-harm, though that may well be part of it. It is more about the way the terminally hopeless reach a state of grace only while performing nihilistic songs. It is a denial of death at the same moment that death eviscerates life. A rising from the ashes.

The folk revival’s obsession with the undead past inspires Marcus, and that makes the “Jim Jones” chapter an unusually deep one. Of all the dozens of then-young musicians mentioned in Folk Music, Marcus is fondest of Mike Seeger, and some of his best writing involves Seeger and the New Lost City Ramblers, who “dressed like accountants from the 1920s” and devoted themselves to old-time music as if the body and soul of it were entrusted to them. Dylan wrote that Mike Seeger was “a romantic, egalitarian and revolutionary type all at once. He had chivalry in his blood.” Marcus’s pages on Seeger are infused with a heightened sensitivity, sans his frequent overwriting. He mentions Seeger’s desire to become one with the mountain musicians he adores, but his class and New York background forbid the transformation, despite his unalloyed passion and sumptuous skill.

“He was a warm, open, skeptical person,” Marcus writes, “but his eyes were like two curses upon himself…. Compared to his onetime student Bob Dylan there was a certain colorlessness in his voice. It was (Dylan’s) engine of empathy…. Dylan’s sense of identification with other people was greater: real, fictional, alive, dead.”

Every major book about Dylan needs a big theory, and this is Marcus’s. At first, calling it empathy might sound ludicrous, knowing what a mean, cold character Dylan can be in real life. But Marcus is talking about empathy divorced from personal life: it is a matter of singing and writing from inside the chosen character. To an extent, it is a solid theory. It is the flip side of the usual line, which schematizes Dylan as a series of masks. One way of understanding the point might be to see Dylan as the “method actor” of song. Dylan himself has explained more than once that he sees other people in himself, even becoming them. (While receiving an award less than a month after JFK’s death, he got himself in big trouble by saying about Lee Harvey Oswald: “I saw things that he felt in me.”)

Discursive, even wildly digressive writing has always been the author’s métier. I suggest one shouldn’t read too much at one sitting, or you’ll get lost in the twisty sentences. (Perhaps the style is Marcus’s way of becoming “the old, weird America.”) At its best, as in the first chapter, “Blowin’ in the Wind,” Marcus brings it all, so to speak, back home. The critic knew about Dylan by 1963, when he was 18 and Dylan was 22. He was struck by the songs on Freewheelin’, but did not care for “Blowin’ in the Wind.” The Peter, Paul & Mary hit version, he thought, merely flattered its audience. A friend, a fellow snooty teen, called it “ersatz.” It took decades of listening to Dylan sing it for the song to seep into Marcus’s adult imagination. Ironically, an essay he wrote about the song for a children’s book is among the present book’s truest, most moving writing. The song’s compelling international history is dissected by the long chapter’s close, and most of the digressions are to be savored.

The ’60s were hallowed years for Marcus. “It was a time when music and politics were locked together,” he writes, “when so often they spoke the same languages.” He eloquently grieves the onset of the Reagan-Thatcher era, which decimated the idea of community, diminished the notion of “the public square, of the value or even existence of civic virtue.” One of the book’s virtues is the way it refuses to cast aspersions on the counterculture merely because of its brevity and lack of practicality.

At its weakest, the book resembles casual note-taking, or stream-of-consciousness rambles and extended suppositions. But since Marcus focuses, as usual, on coincidence, charisma, spirit, metaphor — the seeming ghostly magic of how the culture plays out — his vague, allusive thinking does not sink his essay’s arguments. In fact, they aren’t arguments at all — more like exercises in lyrical persuasion. He loves to go one step too far. Not only does Marcus give the Dylan line “Ain’t talkin’/just walkin'” extensive poetic examination, but he then has to jump further: he imagines explorer “John Smith mouthing it to himself as he took his first steps into Virginia” in 1607.

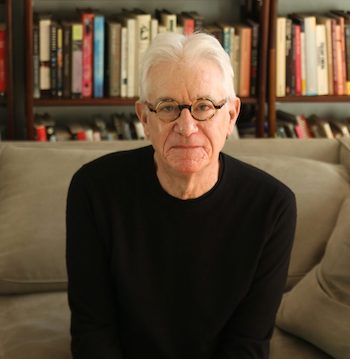

Greil Marcus is the author of Folk Music. Photo: Ida Lodemel Tvedt

Folk Music frequently quotes the “indy press” commentators of the times, often a whole page at a clip. While this could be seen as padding, it is clearly a means to honor the era’s array of conflicting voices. Oddly, Marcus never argues with these 60 year-old writings, even when they contradict all that he believes. The two editors of the Little Sandy Review, a hand-stapled, mimeographed periodical created by two folk-music obsessed students at the University of Minnesota in 1959, exerted an influence on the folk scene way beyond its paltry readership. (It was a time when a single Minneapolis neighborhood called Dinkytown was a center of the folk revival.) The Review despised even the best of Dylan’s political songs and, even more perversely, called him a has-been in 1965, the same month Bringing It All Back Home was released! (Was this payback for Dylan pilfering the editors’ folk records back in 1960?)

At points the digressive style can seem like nervy brilliance, at others, idle whimsy. What ennobles the book is Marcus’s love for his underlying subject: the soulful search for a truer America.

Marcus is one of the very few music writers who refuses to soft-pedal Dylan’s artistic descent in middle age. His slide into cultural irrelevance and creative doldrums began, he believes, with the Christian albums of the late ’70s, and, as a songwriter, he staggered through nearly 20 lost, sputtering years. Marcus credits Dylan’s trip back to his roots — his two solo albums of ancient folk and blues tunes in 1993 and ’94 — for spurring him on to artistic resurrection. He uses a long passage from Dylan’s own memoir, Chronicles, to effectively confirm his own dour appraisal of Dylan’s many dire years. But Marcus also slams Dylan with negative comments targeted at some of his greatest early songs. Regarding Dylan’s third album, 1964’s The Times They Are a Changin’, he only raves about “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.” He dismisses the title track as a mere anthem, never mentioning that it was anthemic by design, and became the single most influential protest song of the decade. Just consider the other topical and love songs on that LP: “With God on Our Side,” “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” “When the Ship Comes In,” “One Too Many Mornings” and “Boots of Spanish Leather.” True, it isn’t quite at the level of Freewheelin’ and lacks humor. But still, the record is an enduring monument of astonishing songwriting. The album was recorded before JFK’s death and released afterward, but the dark tone remained true to the times.

The most egregious chapter in terms of fanciful thematic thinking is titled “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll/1964.” It begins in glorious Marcus style. There are quotes from Aristotle, Hannah Arendt, and a now obscure musician and writer named Sandy Darlington — all of them touching on “a way of life we believe in.” The topic is what this country’s founding fathers called “civic virtue.” “No song exists outside the political” dimension, Marcus writes. He then spends half the chapter on Dylan’s stern, stirring ballad, inspired by a newspaper account of the day, about a rich man who brutally killed his maid, Hattie Carroll, “for no reason,” and earned a mere slap on the wrist in court. Marcus then argues that, while the 1964 Dylan ballad may come from a different social milieu than “O Superman” — Laurie Anderson’s 1981 spooky avant-garde soundscape — “they are the same song.” Greil then goes on to focus — for the entire second half of his long chapter — on the twisting tale of Anderson’s rise from impoverished obscurity to commercial success, all without a stage-show, or even a record label… because of the electronic song “O Superman.” It’s definitely an interesting tale. But I kept wondering: what is the connection here? Why is it “the same song”? And, by page 32, we are finally given the answer. The songs were separately quoted, many years after their releases, by famous performers, both without referencing the songwriters in question, so that both songs had become, in some vague Marcus-like sense, akin to folk material. That’s it! That’s the whole deal! James Earl Jones, on the TV cop show Homicide, quoted a verse from “Hattie Carroll.” At a Fleetwood Mac concert, Lindsey Buckingham quoted words from “O Superman,” without appellation, not even as part of a song. It was simply stage patter. The only other link might be that both songs have a social/political resonance. But, then again, Marcus insists that all songs do.

Bob Dylan in 2006. Photo: William Claxton

This is the thing with Greil Marcus. He seems to connect everything from Hannah Arendt to the Archies, from Jean Ritchie to Lionel Ritchie to Salman Rushdie, D.H. Lawrence, Fenimore Cooper, Christopher Guest, and Ovid. The most abstract, nebulous connection — often with a pleasingly cosmic bent — is proposed, not only as a ghost of a theory but, once stated, as a stone monumental fact. Decades converge. The world fuses. Coincidence is fate. The zany goes cosmic. A daydreamed thought-stream becomes a raging river. Allusion becomes illusion.

In the age of Google, his lists become easier to compound than ever. No wonder he seems to like Dylan’s “Murder Most Foul,” a pell-mell list of song titles, stock phrases, and famed names. In the end, Bob and Greil have something more in common than their births in the ’40s and their love of the opaque. They are both at their best when telling stories.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.

Tagged: Bob-Dylan, Daniel Gewertz, Folk Music -- A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs, Greil Marcus