Visual Arts Review: BarabásiLab — Where Art and Technology Meet, Beautifully

By Mark Favermann

This BarabásiLab exhibition is inspiring because it exemplifies such a powerful integration of art and technology.

Data Draws Data by BarabásiLab, presented by Boston CyberArts at 141 Green St, Boston, through May 22.

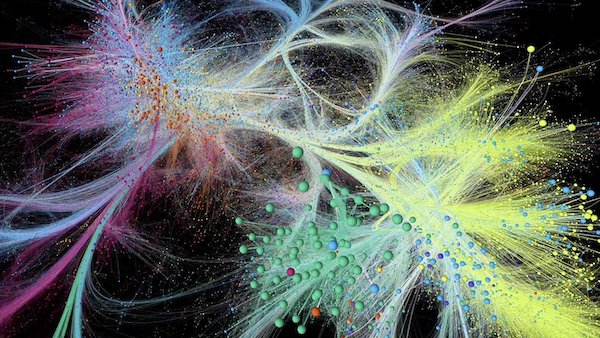

150 Years of Nature, by Alice Grishchenko for the publication “Nature’s Reach: Narrow Work Has Broad Impact,” by A.-L. Barabási, A. J. Gates, A. Grishchenko, Q. Ke, and O. Varol, Nature (November 6, 2019)

The ’80s and ’90s were decades of digital technical experimentation. Essentially, tech geeks wrestled with and then applied various software approaches to what they deemed to be examples of graphic communication and “artworks.” Previously, the intertwining of art and technology works had been created by trained artists or at least reflected a focus on aesthetics. But around four decades or so ago that arrangement seismically shifted. In many areas of visual expression — including graphic design, print (magazines, newspapers, etc.) — technology predominated over visual quality. And, because digital formatting for print was so bad — to the point of being unreadable — the visuals of this work were often ragged and unprofessional. This situation also strongly permeated academic and professional graphs and charts. The media tried to be the message but often failed miserably

Things became so topsy-turvy that graphic designers were often replaced by trendy technicians for whom aesthetics were of no interest. There was an eccentric democratic spirit to this trend: anyone with a computer and Adobe software could call herself an artist. In terms of artistic accomplishment, it was a rather murky, visually unsatisfactory time. Thankfully, both digital technology and those who used it to make art evolved in an exciting direction. Today, digital art, at its best, is a marriage of the technical and aesthetic, much like the traditional visual and plastic media.

Mouse Brain, by Brum Jose, Alice Grishchenko, Nima Dehmami, Albert-László Barabási and Mauro Martino

One of the major challenges in this century is how we are going to come to terms with a technological explosion that is radically affecting us on almost every level — political, social, financial, and even interpersonal. We have become networked, through social media, for the good, the bad, and, unfortunately, the ugly. Northeastern University’s BarabásiLab was established in 2007 to help us understand this reality. Specifically, the organization is dedicated to a deeper understanding of networks of all kinds. Founded by Albert-László Barabási (born in Romania), the BarabásiLab, explores how networks emerge, progress, and evolve. The intent is to express what networks best look like in ways that will facilitate our understanding of complex systems.

Since 1995, when Barabási presented a conference paper that included an enthralling set of illustrations of an invasive network, the academic has emphasized making his research about a wide range of networks visual and available via highly defined, compelling images. Areas of interest have included metabolic and genetic networks, including visualizing how proteins, substrates, and genes interact in a cell. Pictures of social networks quantify the interactions between people. Interactions are often envisioned as webs: the internet is a complex web of computers; ecological systems can be best described as a web of species. The Lab looks at the network science used in medicine, pharmacy, and physics, but it also researches infrastructures, social systems, and developmental processes.

The work of the Lab has questioned the notion of random graph theory. As it investigates the structure of the World Wide Web, the Internet, cellular and social networks, the Lab has discovered that networks in nature follow a common blueprint that displays scale-free characteristics. This discovery represents a significant paradigm shift, encouraging a turn to dynamic network modeling that has had a strong impact on research on the nature of networks. The Lab is also looking at the various tolerances of complex networks.

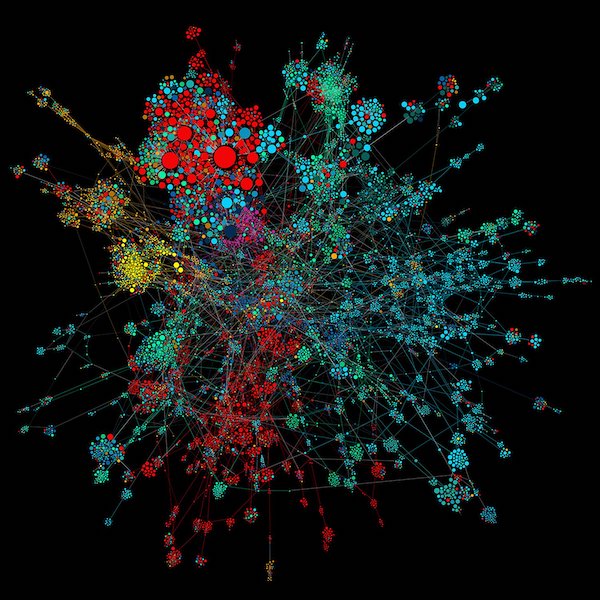

The Art Network, by Alice Grishchenko, Samuel P. Fraiberger, Roberta Sinatra, Magnus Resch, Christoph Riedl, and Albert-László Barabási

Made up of over 30 individuals, the Lab includes postdoctoral researchers and students who are working toward their PhDs. The group includes physicists, computer scientists, neuroscientists, designers/artists, and even art historians. In addition to coming up with theoretical breakthroughs, the Lab has also become recognized for producing highly creative and accessible visualizations, 2-D and 3-D representations of complex contemporary research outcomes. These pictures are both informative and elegantly beautiful. The Lab is providing masterful examples of what can be accomplished when artistic deftness and digital sophistication collaborate.

The current exhilarating exhibition at the Boston Cyberarts Gallery, curated by George Fifield, is part of an international series of BarabásiLab exhibitions. This work has appeared at other institutions, including London’s Serpentine Gallery, The Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York, the Ludwig Museum in Budapest, and the ZKM in Karlsruhe, Germany. This exhibit demonstrates how powerfully BarabásiLab has developed a visual vocabulary for complex systems, and how this vocabulary often relies on the tropes of visual art. Of course, there are innovations as well. More data is being produced per day now than at any time in history, and the Lab suggests that visualizations — of characteristic nodes and networks — might be the best way to keep up with the ever-shifting parameters and patterns.

The exhibition’s aim is to provide a comprehensive overview of the kinds of visualization developed by BarabásiLab. The show’s strength is easy to locate: the sheer beauty of its individual animated images, reflections of a team that involved scientists, artists, and designers alike. Several of the artworks are stunning both in terms of looks and content. A trio of highlights: Alice Grishchenko’s 150 Years of Nature presents the history of science, evolution, and decimation as a colorfully cosmic image; The Art Network (Alice Grishchenko, Samuel P. Fraiberger, Roberta Sinatra, Magnus Resch, Christoph Riedl, and Albert-László Barabási) draws on the location of art institutions with precise color and form to point out their interconnectivity; and Mouse Brain (Brum Jose, Alice Grishchenko, Nima Dehmami, Albert-László Barabási, and Mauro Martino, uses a blue 3-D image to display the title animal’s synapsis, neuron clusters (nuclei and colliculi), and neural pathways.

This BarabásiLab exhibition is inspiring because it exemplifies a powerful integration of art and technology. Science and art elevate each other in a search for hidden patterns in complex systems that determine our biological and social existence.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is associate editor of Arts Fuse.

Tagged: art, BarabásiLab, Boston Cyberarts, Boston Cyberarts Gallery, George Fifield, Mark Favermann