WATCH CLOSELY: “Severance” — All Work and No Life

By Peg Aloi

Without letter-perfect performances from the actors I’m not sure Severance would work anywhere near as well as it does.

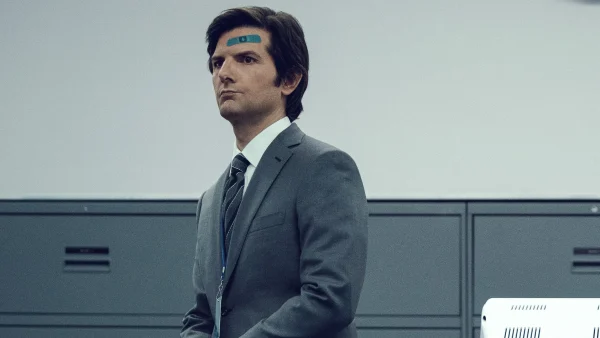

Adam Scott in Severance.

Opening scene of Severance: A white woman with red hair wearing heels and a form fitting dress lies on a conference room table, unconscious. A disembodied voice booms from the tabletop speaker: “Who are you?” The woman gradually wakes but is disoriented. The interviewer prompts her to answer a “short survey” which it suggests might make her feel “right as rain.” She’s asked to name one of the fifty states — it’s the only one of the questions she can answer. She finds the questions annoying and confusing. The last question, whether she can remember the color of her mother’s eyes, seems to cause her sadness and despair.

Isn’t this a dystopia that’s so plausible you can taste it? Science fiction often seems to be nothing but escapism because it draws on so many occurrences and situations that are simply not physically real or even possible. But speculative fiction (along the lines of Black Mirror) takes elements that are eerily close to reality and mixes them into plausibly alarming scenarios (technological, social, political, environmental). The results are cautionary tales that, at their best, illuminate our very near future. Dystopia, where a society has gone off the rails, is the outcome of a social order that has become oppressive or perversely cruel (think The Handmaid’s Tale).

In recent months, Americans have seen some shit. The pandemic, economic and social instability, the continuing climate crisis, emboldened agents of fascism, and the rise of oppressive political factions who seek to do away with basic freedoms, such as voting and reproductive autonomy. It’s little wonder that our entertainment is reflecting the dark and dreadful back to us. Among other shake-ups, pandemic life has put office culture under scrutiny. Many people who formerly worked in offices moved to working remotely from home for the last two years; the upshot is that the idea of returning to the workplace is fraught with revulsion as well as reassurance. In Severance, the series created by Dan Erickson and executive produced by Ben Stiller (who also directed a few episodes), the idea of the workplace as a cold, sterile, cruel environment that negates the most rewarding aspects of life has been taken to its logical conclusion.

The workplace here is a shadowy corporation called Lumon; no one quite knows what they make or what they do and the departments are separate from one another, so information is not easily exchanged. Severance focuses on a department with four employees: Pete (Yul Vazquez) has recently left and the woman on the table, Helly (Britt Lower), is his replacement. There’s Mark (Big Little Lies‘ Adam Scott), the seeming protagonist, who has just been promoted to department head (his is the disembodied voice asking Helly who she is). There’s polite but officious Irving (John Turturro in an incandescent performance) and wisecracking, cynical Dylan (Zach Cherry). Their work is known as “macro data refinement,” and they don’t know what the coded data they work with refers to. The company was founded by a man whose legacy is honored in strange cult-like ways inside the building, including a life-size replica of his house, inspirational quotes from his magnum opus hanging in every room, and a museum of wax figures of all the previous Lumon CEOs.

Many of Lumon’s employees have opted to go through a procedure called “severance” (invented by the founder), in which a chip is surgically implanted in their brains which creates a divide between their work selves (referred to as “innies”) and their outside of work selves (“outies”). Their innies have no knowledge or recollection of who they are outside the office; the same is true for the outies, who only know they go to work and come home every day. The shift in consciousness occurs in the elevator. In an instant the employees’ facial expressions change; they seem careworn, aloof, and somehow colder. Mark and Pete were best friends at work, but know nothing of one another outside of Lumon. As Helly becomes integrated into her new role, she brings a spark of rebellion to the team, who gradually begin to wonder if choosing severance was their best option.

This inventive conceit provides plenty of tension and suspense. But without letter-perfect performances from the actors I’m not sure Severance would work anywhere near as well as it does. Adam Scott is particularly fascinating as a man who has chosen oblivion over grief. Patricia Arquette is phenomenal in a dual role: she’s Mark’s boss and also his neighbor (though it takes a while to sort out if she, too, has been subjected to the severance procedure). Tramell Tillman is brilliant as the ebullient office manager and arranger of odd morale-boosting events, like “music and dance experiences” and “waffle parties,” which are seen as coveted perks by employees. Then there’s the delightful Christopher Walken, senior employee in the company’s Optics and Design department, a secretive office that no one seems to know much about. Outside of work, Mark enjoys a close relationship with his sister Devon (Jen Tullock), who is pregnant and married to a rather pretentious author of self-help books (Orange is the New Black‘s Michael Chernus), one of which turns out to be a key plot element. Mark’s friends know of his severance and there’s a sense that people who have chosen it are judged harshly by others. Severance as a workplace practice is being hotly debated.

The pristine production design of the show is full of striking and memorable visuals — this fictional workplace is a behemoth built out of glass and metal, with tasteful touches of color added here and there. And the building has the brightest white hallways one could imagine, suggesting a liminal place that exists apart from time. Even the snacks in the vending machine don’t seem quite real. But, beneath the chilly surfaces of things, there are striking revelations of beauty and sensuality, as if these are somehow compensations for the loss of humanity undergone by severed employees. The show’s central metaphor is powerful and plausible. There’s no doubt that many viewers will find themselves examining their own work-life balance. But, despite its social relevance, Severance isn’t preachy or contrived; it’s thrilling, fascinating, and ultimately terrifying.

Peg Aloi is a former film critic for the Boston Phoenix and member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. She taught film studies in Boston for over a decade. She writes on film, TV, and culture for web publications like Vice, Polygon, Bustle, Mic, Orlando Weekly, Crooked Marquee, and Bloody Disgusting. Her blog “The Witching Hour” can be found at themediawitch.com.