Book Review: “Thank You, Mr. Nixon” — East Meets West, Again and Again

By Jacqueline Houton

The author of The Resisters returns with a timely collection of stories about the connections and contradictions linking America and China.

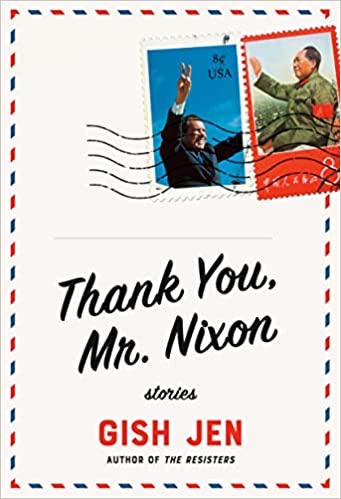

Thank You, Mr. Nixon by Gish Jen. Knopf, 260 pages, $28.

This winter marks half a century since Tricky Dick touched down in China, ending 25 years of diplomatic isolation. Acclaimed writer Gish Jen — a visiting professor at Harvard who divides her time between Cambridge and Vermont — makes the geopolitics personal in her ninth book, Thank You, Mr. Nixon. Exploring five decades of US-China relations through the everyday lives of characters in 11 linked stories, she takes precise measure of cultural and generational divides carved out by the course of history.

The book begins with the title story, which takes the form of a letter sent from heaven and addressed to Mr. Richard Nixon of “Ninth Ring Road, Pit 1A.” Riffing on a famous photo, Jen conjures a correspondent who now goes by her American name, Tricia Sang, and was a little girl when she briefly met the president in Hangzhou’s West Lake Park during his history-making 1972 visit. On that February day, Tricia wore a coat pieced together from two other coats by her mother, who at the time was living more than a hundred miles away, having been assigned to sew in a Shanghai factory. She thought her new coat was the most beautiful in the world until she saw pictures of the one Pat Nixon wore stepping off Air Force One, a tea-length red number that stood out in a sea of black, gray, and dark blue garments.

Twenty years before, Nixon had famously touted the humble bona fides of his wife’s “good Republican cloth coat,” but this coat meant something very different in China: “A red coat was bourgeois, after all. It was antirevolutionary. It was corrupt and corrupting. Couldn’t we feel its pull? That was because it was venal. Imperialist. American. Beautiful.” For months afterward, young Tricia drew pictures of people and animals clad in red coats. And, when economic reforms allowed her mother to come home and the family to start their own small coat business, Tricia copied the cut of Pat’s coat for her first design. Later, having realized that American customers are repelled by a “Made in China” label, the family bought a shuttered factory so that buttons and linings could be finished in Italy, where cultural differences led to friction between workers and employers. “Even now there are Italian people who will not hang out on the same cloud as us,” she notes.

The whimsical premise and Tricia’s almost chipper tone only underscore the glimpses of darkness in the story — a reference to Red Guards beating people to death in public, a nod to the instructions received by the “background children” chosen for Nixon’s visit, who knew they were not to understand journalists’ questions, even if the translator’s Mandarin was perfect. And the scholars in paradise are still arguing over whether Chairman Mao killed 45 million people or merely 25 million, leaving Tricia to wonder why Nixon was consigned to the ninth ring of hell. “Of course, between Vietnam and Cambodia, you had some blood under your fingernails, too,” she acknowledges. Nonetheless, she thanks him for bringing so many coats into their lives. In heaven, she wears a new one every day.

We find out how Tricia ended up in heaven 200 pages later via a brief reference in another story, “No More Maybe,” narrated by a friend who ran a clothing store in China that stocked styles designed by Tricia’s proteges. Now seven months pregnant and living in the US — precariously, thanks to a minor discrepancy on her husband’s green card paperwork, a misunderstanding caused by differences in American and Chinese naming conventions — the woman announces that the baby is kicking at a tense moment to defuse conflict between her visiting in-laws. “If I am upset, the baby will be upset. That is how Chinese people think,” she says. “One thing always affects something else.” That observation seems to underpin the book’s architecture: While we watch ties between America and China tighten as characters participate in commerce, tourism, immigration, and adoption, minor figures from one story resurface as central ones in another, and vice versa, their lives becoming as intricately entwined as the push pins on an evidence board.

Writer Gish Jen. Photo: Basso Cannarsa.

These kinds of connections are key to the collection’s structure, but thematically, Jen, a daughter of immigrants, is just as interested in moments of disconnection, in gaps and gulfs and things that get lost in translation between American and Chinese characters — especially between family members of different generations. That’s the case in “It’s the Great Wall!” a story in which the American-born Grace visits a newly open-to-tourists China with her husband, Gideon, and her mother, Opal, who hopes to see her sisters after nearly forty years away. Opal explains customs to her sometimes culture-shocked daughter and son-in-law and eventually gets roped into a role as translator for their whole tour group, facing the fraught task of relaying cringe-worthy questions to their guide, Comrade Sun, an overwhelmed first-timer who speaks limited English and has to write an official report every night. For Opal, whose father was killed during the Cultural Revolution, the act of translation becomes exhausting, even potentially perilous. And though she is ultimately able to reconnect with some of her family, Opal finds you really can’t go home again. Witnessing her grief leaves Grace desperate to return to her own four-year-old daughter, Amaryllis, back in the States.

The book gradually moves forward through the decades: We meet Grace’s daughter again as a 40-year-old in the story “Amaryllis,” and the final tale, “Detective Dog,” takes us right into the Covid era. Indeed, the collection is powerfully pertinent: it arrives at a time that has seen a rise in hate crimes against Asian Americans, fueled by the racist rhetoric of our previous president. China — the subject of frequent headlines heralding a new cold war as well as articles cataloging countless human rights abuses, including the current crackdown on dissent in Hong Kong — is a country whose history most Americans know little about. But it has become the United States’ number-one trading partner, its citizens sewing our American flags and manufacturing our toys under abusive conditions we prefer not to think about. Of course, that might also be said of working conditions in our own country.

Jen presents a prismatic view of people and places that are worlds apart and yet may have more common ground than many care to admit. The story “Rothko, Rothko,” centered on an undocumented artist named Ming, offers a reminder that China is not the only place where the government can arrange to make people disappear. When the mother-in-law in “No More Maybe” claims that Americans are too lazy to conduct mass surveillance, her husband, despite suffering from what may be early-stage dementia, manages to recall the title of the movie Snowden, avowing “They spy here, too.” And when a smug professor in her tour group asks, “So they [Chinese people] preach moderation when in fact they are completely and utterly immoderate?” Opal is quick with a rejoinder: “The way that Americans preach justice?”

The stories alternate between first and third person, allowing Jen to adopt a range of tones and styles, but the collection is united by her blend of sharp observation and compassion for her characters. (Even Tory, half of a clueless white couple from the tour group in “It’s the Great Wall!” who later embark on an ill-fated import venture and adopt a daughter from China in “A Tea Tale,” is afforded a moment of genuine pathos.) Taken together, the stories have the sweep and scope of a novel, one that’s by turns humorous and harrowing and, above all, humane.

Jacqueline Houton is an editor and writer based in Cambridge. A former editor of The Improper Bostonian and managing editor of The Phoenix and STUFF magazine (RIP x3), she currently copyedits kids’ and YA books by day and serves as senior editor at Boston Art Review. Her writing has appeared in Big Red & Shiny, Bitch magazine, Boston magazine, Pangyrus, Publishers Weekly, and other publications.