Arts Remembrance: Stephen Sondheim – Musical Theater Mourns the Passing of a Giant

By Christopher Caggiano

Stephen Sondheim was the most influential musical-theater artist of the modern era. His death leaves a permanent hole in the art form and in the hearts of his fans.

HBO’s tribute film Six by Sondheim: James Lapine, Stephen Sondheim, Jackie Hoffman, America Ferrera, Darren Criss, Laura Osnes, and Jeremy Jordan.

We, the faithful, knew this day would come. But that doesn’t make the loss any easier. I’m referring, of course, to the recent passing of the great Stephen Sondheim, who died on Friday, November 26, at the age of 91.

It would be hard to overstate Stephen Sondheim’s impact on musical theater. For one, Sondheim raised the standards of what constituted a great musical, some might say impossibly high. Along the way, he crafted thousands of unforgettable songs and multiple musical masterworks, including Company, Sweeney Todd, and Sunday in the Park with George.

His Broadway shows weren’t always profitable in their initial runs — in fact, only a handful made any money. But most of those shows have lived on in multiple revivals, movie versions, and countless local and community productions. Even his outright flops like Anyone Can Whistle, Merrily We Roll Along, and Pacific Overtures, contain fascinating elements that attest to Sondheim’s genius.

After a short period of anonymity, Sondheim made an auspicious Broadway debut in 1957 writing the lyrics for West Side Story, followed closely by Gypsy, inarguably two of the greatest musicals ever created. But what Sondheim really wanted to do was craft both the music and the lyrics, and that he did, ultimately placing him in an exclusive pantheon of composer/lyricists that includes Jerry Herman, Noël Coward, and Cole Porter.

Later in his career, after his most productive period during the ’70s and ’80s, the Sondheim legend grew to nearly hyperbolic heights, with tributes and honors pouring in on a seemingly annual basis. Sondheim was characteristically sardonic about his supposed godlike status, even poking fun at himself by contributing a new song called “God” to the 2010 Broadway revue Sondheim on Sondheim. In the song, Sondheim not only refers to himself as “odd,” but the sparse, fragmented lines with an almost complete lack of actual information suggest that fans often revere him without really understanding what his songs and shows are about.

But surely even Sondheim himself would admit that the adulation was a welcome change from the harsh initial reactions to many, if not all, of his shows. Critics and audiences were often confused, even put off by the nonlinear structure and harsh, unsentimental tone of his shows, particularly those he wrote with producer/director Harold Prince: Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, Pacific Overtures, Sweeney Todd, and Merrily We Roll Along. While most of these musicals are now considered classic among the cognoscenti, each was greeted with some mixture of coldness, bewilderment, even hostility. Each show had its adherents, but Sondheim, whether due to his choice of subject matter or his uncompromising search for the truth within each moment, was never to see one of his shows greeted with unanimous praise.

As the long-reigning elder statesman of musical theater, Sondheim generously gave of his time to mentor a new generation of musical theater artists, notably fellow Pulitzer Prize-winners Jonathan Larson and Lin-Manuel Miranda. No doubt this was an extension of Sondheim’s relationship with Oscar Hammerstein, who literally sat Sondheim down and taught him how to write a show. So great was Hammerstein’s influence that Sondheim famously said that if Hammerstein had been a geologist, he probably would have become a geologist as well.

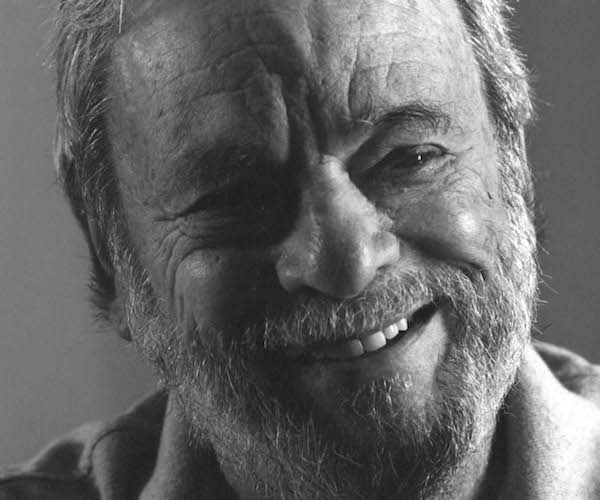

Stephen Sondheim at the age of 80.

Although Hammerstein had laid the foundation for what would constitute quality musical theater, Sondheim built upon that foundation in ways that both honored and rejected tradition. Sondheim modernized the musical and inspired subsequent generations of creators to keep the edifice rising. He not only brought the subject matter to deeper and more meaningful places, he also experimented with form in ways no one had thought of before.

Sondheim’s shows changed the overall tone of musicals, veering the form to a more serious and self-reflective space. Instead of relying on comforting fantasies, Sondheim often directly addressed the complexities of the day. His work often contained multiple levels of reality, with characters outside the scene commenting on the proceedings. The Brechtian elements, rather than alienating the audience, created a discomfiting sense of identification. Sondheim shows are never easy to watch. That is, if you’re paying attention.

Along with director Harold Prince, Sondheim proved that musical theater could be intelligent and ambitious. Together they pioneered a new musical form that was more conceptual, driven by ideas rather than events, and often held in place by a framing device: a 35th birthday party, a Ziegfeld Follies-type revue, a Kabuki/Noh play, a sinister carnival sideshow.

Sondheim and Prince famously parted ways after the public humiliation of Merrily We Roll Along and its flat-out rejection by critics and audiences alike. Sondheim seriously considered quitting theater altogether to write mystery novels. We all owe playwright/director James Lapine an eternal debt for luring Sondheim back to the theater with a new partnership that produced Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods, and Passion, among other projects.

The shift in the tone, form, and execution of Sondheim’s shows when he switched from Prince to Lapine reveals a great deal about the influence his collaborators had on his work. Prince brought out Sondheim’s incisiveness and cynicism. You can hear it in the jagged edges of the opening guitar chords in Company or the roiling accompaniment to the prologue of Sweeney Todd. Lapine manifested Sondheim’s softer, more philosophical side, which appears in the rounded contours of the arpeggiated orchestrations to Sunday in the Park and Into the Woods.

Sondheim liked to say that he almost never wrote autobiographically. He was, of course, being literal. He only ever wrote directly about his own experiences in the song “Opening Doors” from Merrily We Roll Along, in which he channeled his experience with friends Mary Rodgers and Sheldon Harnick when they were all struggling to make names for themselves in the ’50s. In a more figurative sense, though, Sondheim poured himself into every song, every show, every character. He even admitted that he saw much of himself in George from Sunday in the Park, and even identified with certain aspects of Sweeney in Sweeney Todd.

To experience Sondheim’s shows is to get to know Sondheim the man. Sondheim had a difficult childhood: his parents divorced quite acrimoniously when he was very young, and his mentally unbalanced mother used him as a pawn to exact revenge on her ex-husband. As a result, Sondheim escaped by becoming a sort of foster son to Oscar Hammerstein, who welcomed the young Sondheim into his home, even treating him better than his own children, much to their discontent.

An only child and the product of a more-than-broken home, Sondheim saw his collaborators as his family, particularly the ones who wrote the libretti to his shows: Arthur Laurents, Larry Gelbart, George Furth, John Weidman, James Goldman, Hugh Wheeler, and James Lapine. People often mistakenly think that Sondheim also wrote the books to his shows, but he never did, and said that he wouldn’t be interested in doing so. Each show he created presented an opportunity to surround himself with like-minded people, draw inspiration from them, to the point of appropriating moments in their dialogue to convert into songs.

Stephen Sondheim — to address all of Sondheim’s innovations and significance would take volumes.

To address all of Sondheim’s innovations and significance would take volumes, many of which have already been written. But there’s one song that encapsulates much of what made a Sondheim show special. When he wrote Company, Sondheim struggled with finding the right song to end the second act. He made various attempts during the show’s tryout period in Boston, but the results were either too harsh or too optimistic. The story needed to end on a note of contradiction: the main character Bobby needs to embrace the fact that marriage comes with many pros and cons. Rather than avoiding marriage entirely, Bobby must accept the good with the bad.

The result was “Being Alive.” To portray Bobby’s decision, Sondheim employed a very simple but extremely effective shift in the song’s lyric. The words start in the hypothetical: “Someone to hold you too close/Someone to hurt you too deep/Someone to sit in your chair/And ruin your sleep…” By the end of the song, the lyric makes a subtle but crucial shift to “Somebody hold me too close/Somebody hurt me too deep.” Sondheim shows us that Bobby is ready to commit to another person, despite the contradictions involved. Perhaps even because of those contradictions.

Sondheim would return to the theme of taking action in Sunday in the Park with George. At the end of the show, the main female character, Dot, is exhorting the central male figure, George, to break free of the emotional shackles that are hampering his productivity. For this moment, Sondheim crafts two marvelously pithy and evocative moments that, now that Sondheim is gone, nonetheless can serve to continue his mentorship of aspiring theater artists:

I chose and my world was shaken

So what?

The choice may have been mistaken

The choosing was not

You have to move on

Stop worrying if your vision is new

Let others make that decision

They usually do

You keep moving on

Sondheim’s message is clear: Make the choice. Damn the consequences. Give us more to see.

Christopher Caggiano is a freelance writer and editor living in Boston. He has written about theater for a variety of outlets, including TheaterMania.com, American Theatre, and Dramatics magazine. He also taught musical-theater history for 16 years and is working on a number of book projects based on his research.

As you imply, I think Sondheim recognized the importance of his collaborators. You mention his producers and writers of the Books but the orchestrators–chiefly Jonathan Tunick–should be noted as other indispensable contributors.

Oh, without a doubt. The great Jonathan Tunick contributed immeasurably to the artistic success of Sondheim’s shows.