Book Review: “The Anomaly” — We Know Less Than We Think

By Thomas Filbin

The Anomaly is an entertaining philosophical critique, suggesting that nothing is as it seems, knowledge is imperfect, and the human predicament will perhaps always be more inexplicable than we can admit to ourselves.

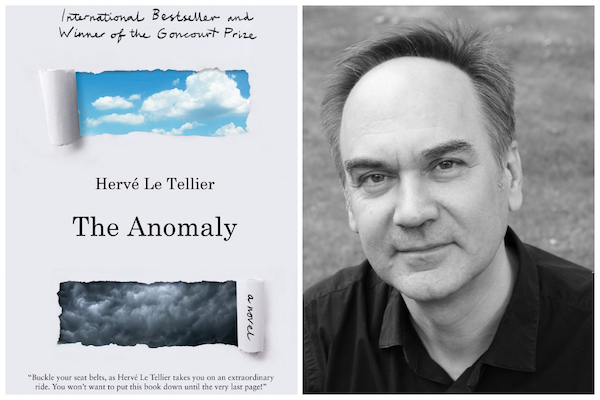

The Anomaly by Hervé Le Tellier. Translated from the French by Adriana Hunter. Other Press. 400 pp., $16.99.

Hervé Le Tellier’s latest novel, The Anomaly, won the Prix Goncourt in 2020, putting him in the select company of Marcel Proust (1919), André Malraux (1933), Simone de Beauvoir (1954), Romain Gary (1956), and Marguerite Duras (1984). Where Le Tellier differs from these earlier awardees is that his book self-consciously embraces genre fiction. The Anomaly takes the narrative form of a script for a pot-modern sci-fi made-for-television series. There are also elements of literary thriller and social satire. Unifying all these strands is Le Tellier’s admirable skill at keeping readers in suspense: for a long time it is not clear what this story is “about,” yet he continues to draw us into an increasingly complex plot, which is laid out in a succession of clues and strange coincidences. No spoilers here. I can say authorities round up the passengers of Air France flight 006, a Boeing 787, from Paris to New York. It had landed after going through a cataclysmic storm which seems to be both a weather event and some kind of unusual turbulence (perhaps an electromagnetic field?) which nearly destroys the plane. It is June 24, 2021. But soon airport officials realize that the same plane — with the identical crew and passengers and identical damage — landed at JFK 106 days earlier. We do not hear about this Twilight Zone discovery until halfway through the book, which gives Le Tellier enough time to go into the lives and tribulations of the various persons put under examination.

Le Tellier offers plenty of clever insights into the worlds of flawed people whose lives have now become matters of scientific curiosity. In Paris we have a contract killer named Blake, a failed novelist named Victor Miesel, and star-crossed lovers André Vannier and his girlfriend Lucie. The latter pair supply glimpses of contemporary life: it’s filled with self-doubt rather than meaning. André is older than Lucie and their relationship has been slowly disintegrating, a coolness presages the end. “Why couldn’t he see that she’s already left?” she thinks, wanting her freedom but finding it difficult make the final break. André knows he has become an old man in her eyes, a consciousness of mortality compounded by his realization that he will never be young as once he was.

In America, at Princeton University, two other actors assume their roles. Adrian, a brilliant mathematician-analyst, has become “painfully aware that he’s eyeing his coworker Meredith with something alternating between a tense smile and idiotic sentimentality.” After several drinks he gets the courage to approach her, reckoning

his chances of success at twenty-seven percent. They could have gone as high as forty percent if he didn’t stink so terribly of alcohol, but on the other hand, the inebriation will reduce by about sixty percent the suffering incurred by a rejection. He concluded that with such a high chance of failing, he might as well be drunk.

Adrian and Meredith are drawn into the mystery by the US Defense Department, which has taken over the investigation. Somebody has to figure out how to calculate the odds of what happened and come up with a plausible explanation. Weather, foreign aggression, a massive fraud scheme, and supernatural intervention are all considered.

Miesel, the unsuccessful author, somehow triggered the strange events. He has been writing for 15 years and earned next to nothing. He has a small literary prize to his credit and works as a translator. His view of the literary game is cynical, “a farcical train where crooks without tickets take first-class seats with the complicity of incompetent conductors, while modest geniuses are left on the platform.” When he returns from the flight he pens his masterpiece, The Anomaly, in Paris. Overwhelmed by a nebulous anxiety, he falls (or throws himself) from his balcony to his death.

The investigation into the dual landings continues. There are speculations about a cosmic tear, a wormhole in three-dimensional space which allowed the plane and passengers to somehow be replicated. Meredith tries to explain the scientific concept to a high-level confab of scientists, religious figures, and philosophers, and the president of the United States. Perhaps space can fold itself like a sheet of paper, she says, and then be “hyperspace … in ten, eleven, twenty-six dimensions.” Meredith pauses and notes that “the American president sits openmouthed, showing a marked resemblance to a fat grouper with a blond wig.”

The most absorbing aspects of The Anomaly are not generated by its complicated plot, but the world Le Tellier immerses us in. Each chapter is filled with exacting detail: specifics about the investigations, intricacies of avionics, and experts’ view of how the world works. These specifics are precise and reflect enormous research — but to no avail. Perhaps the message here is that, although science is the best instrument we possess to understand the universe, it does not guarantee control. We know less than we think. Every generation falls victim to hubris, the notion that it has progressed to the apex, that it knows most of what can be usefully known. That egotism is inevitably shattered over time. Hey, it was not that long ago when many of us thought that the VHS tapes available at Blockbuster were the ultimate in-home entertainment.

In that sense, The Anomaly is an entertaining philosophical critique, suggesting that nothing is as it seems, knowledge is imperfect, and the human predicament will perhaps always be more inexplicable than we can admit to ourselves. Le Tellier introduces a counterfactual context, but he does not seriously expect readers to accept a sci-fi answer to the problems he has posed. Rather, he wants to undercut our pride in human reason with a healthy dose of epistemological skepticism.

Thomas Filbin is a freelance book critic whose work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Boston Globe, and Hudson Review.

Tagged: Adriana Hunter, Herve Le Tellier, Other Press, The Anomaly

[…] Book Review: “The Anomaly” – We Know Less Than We Think artsfuse.org […]

[…] Thomas Filbin (The Arts Fuse) […]

very interesting to mix philosophy with physics..etc..anyway we are just an instument[like a microscope] with limitation BUT THE FACT THAT WE ARE CURIOUS..MAYBE WE ARE MORE THAN A MACHINE…