Jazz Album Review: A Solo Excursion by Master Pianist Edward Simon

By Michael Ullman

One of pianist Edward Simon’s strengths is his ability to be simultaneously romantic and clear-headed, precise and suggestive.

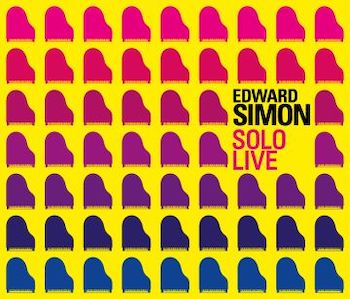

Edward Simon, Solo Live (Ridgeway Records)

Recorded at a concert in Oakland on July 27, 2019, pianist Edward Simon’s Solo Live is the pianist’s first solo album. The 52-year-old seems to have tried everything else, from trios to orchestral pieces. It sounds as if he were adventurous from the start: he was 15 when he left his native Venezuela to go to the Pennsylvania Performance Arts School. Before he left, with brother Marlon on timbales, Simon had a dance band. By the time he was 19, Edward was in New York City playing jazz. Soon he’d be recording with emerging jazz stars like Greg Osby, Bobby Watson, David Binney, and Kevin Eubanks. More recently, he has paid tribute to his home country with his Venezuela Suite (2014) and his Latin American Songbook (Sunnyside 2015). He’s also been the pianist on the SFJazz Collective’s tributes to Miles Davis, Michael Jackson, Joe Henderson, Ornette Coleman, Stevie Wonder, and Thelonious Monk. Those who want the satisfying task of surveying at least part of Simon’s recording career should take a listen to last year’s two-disc anthology, 25 Years (Ridgeway).

Recorded at a concert in Oakland on July 27, 2019, pianist Edward Simon’s Solo Live is the pianist’s first solo album. The 52-year-old seems to have tried everything else, from trios to orchestral pieces. It sounds as if he were adventurous from the start: he was 15 when he left his native Venezuela to go to the Pennsylvania Performance Arts School. Before he left, with brother Marlon on timbales, Simon had a dance band. By the time he was 19, Edward was in New York City playing jazz. Soon he’d be recording with emerging jazz stars like Greg Osby, Bobby Watson, David Binney, and Kevin Eubanks. More recently, he has paid tribute to his home country with his Venezuela Suite (2014) and his Latin American Songbook (Sunnyside 2015). He’s also been the pianist on the SFJazz Collective’s tributes to Miles Davis, Michael Jackson, Joe Henderson, Ornette Coleman, Stevie Wonder, and Thelonious Monk. Those who want the satisfying task of surveying at least part of Simon’s recording career should take a listen to last year’s two-disc anthology, 25 Years (Ridgeway).

Deliberately or not, in his solo concert Simon pays tribute to earlier pianists: Chick Corea and Thelonious Monk. I believe his version of “I Loves You Porgy” is in homage to Bill Evans. In his interpretation, Simon explicitly draws on the freely flowing rhythms of Corea’s take on “Lush Life.” However popular, the song is a strange piece. Written by the prematurely cynical Billy Strayhorn, who began work on his most famous tune when he was 16, “Lush Life” is usually milked for its drama — or really, melodrama. Simon is aware of the song’s implications, including its description of an alcoholic whose cheeks bear “distingué traces.” But rather than move funereally, his approach is set from the beginning: he plays the initial melodic phrases slowly, while decorating them with swirls, trills, and rapidly decorative lines. He doesn’t lose the melody, but he moves it along with nip-and-tuck grace. In the chorus he introduces a little rhythmic pattern in his left hand and plays over it with gradually expanding lines. Simon uses rubato where it fits, almost sending the proceedings out of tempo; then, in contrast, he throws in a few bars of stride. Somehow it all sounds natural.

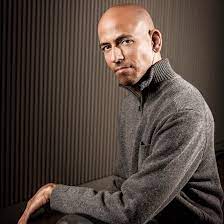

Pianist Edward Simon

Simon then takes on Monk in two tunes: “Monk’s Dream” and “Monk’s Mood.” He is respectful, even though he plays the tunes without attempting to imitate Monk’s characteristically percussive playing, eccentric phrasing, or use of time. That doesn’t mean that Simon’s Monk sounds watered down. Simon has absorbed the pieces, but draws on only parts of the personality of their composer. He begins “Monk’s Dream,” which Monk first recorded for Prestige in 1952, in a brightly boppish style with cheerful right-hand notes poked out percussively over a sparsely distributed number of left-hand chords. When Simon gets to the Monk melody, he mimics some of Monk’s crushed notes, but moves on in what becomes a cheerfully fluent conversation between his hands.

Appropriately, “Monk’s Mood” is slower, more quietly suggestive: it’s a real ballad, and played as such with only occasional dabs of percussiveness. Simon performs firmly: his touch is clean and authoritative. But it’s devoid of Monk’s often slightly aggressive sound. Simon always seems to be on his way; Monk usually emphasizes the moment.

“Country” is the lone original on Solo Live. It’s not exactly in Dolly Parton territory: I imagine Simon was thinking of country spaces rather than American country music. The set ends with a solo version of “I Loves You Porgy,“ from George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. Although dozens of jazz performers, including Billie Holiday, have previously recorded this song, Bill Evans put his indelible imprint on it with the sublime performance found on his 1968 Montreux album. Simon’s unaffected, ruminative statement of the theme displays his ability to be simultaneously romantic and clear-headed, precise and suggestive. The only flaw in this recording is its length, a little over 32 minutes. One wishes the crowd had extorted a few encores from this master pianist.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Brother Edward is one of the most musical pianists on the planet.