Book Review: A Retrograde Shakespearean Shout-Out

By Bill Marx

Shakespearean’s version of the Bard comes off as somewhat Monty Pythonesque — we are usually marching along with “Men Men Men.”

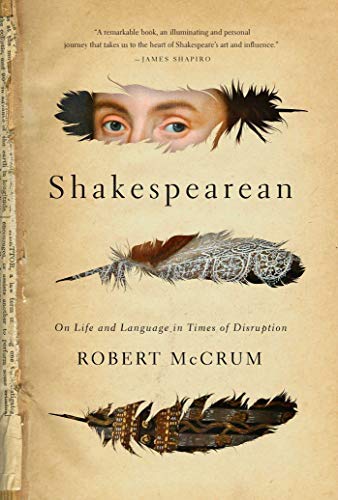

Shakespearean: On Life and Language in Times of Disruption by Robert McCrum. Pegasus, 401 pages, $29.95.

Novelist, former editor-in-chief of Faber & Faber, and associate editor of The Guardian, Robert McCrum loves the Bard well but none too wisely in Shakespearean, his sloppy amalgamation of biography, literary history, and memoir. In this age of climate change, feminism, multicultural voices, mass immigration, and identity politics, bardolatry can’t be as blind (or as privileged) as it was in the days of yore. Encomiums to Shakespeare’s universal genius won’t cut it, not after Harold Bloom pushed the ante sky high when he proclaimed that the Bard had done no less than invented the human, “the inauguration of personality as we have come to understand it.”

Funny how so many of those personalities are outfitted with codpieces: McCrum’s godling of a Shakespeare is generally of the all-male, Merrie Old England variety. Energized by a theatrically inexhaustible ambiguity, the Bard’s plays dramatize the conflicted modern self, assert a stoutly patriotic English identity, take dazzling dramaturgical risks, and reconcile, through negative capability, every polarity under the sun, lyricism and despair, irony and earnestness, militarism and love, etc. McCrum ignores Shakespeare’s memorable female characters as well as his astute examination of the dynamics between the sexes. So Shakespearean‘s version of the Bard comes off as somewhat Monty Pythonesque — we are usually marching along with “Men Men Men.”

To make his claims for transcendence stick, McCrum has to be wary about where he trains his goo-goo eyes. Potential trouble spots abound. The major plays he discusses are Henry V, Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet, and The Tempest. McCrum stays away from anything in the selected texts that might cast serious doubt on his literary idol. For example, he doesn’t grapple with Henry V’s order (a war crime?) to kill the French prisoners. When it comes to the interpretation of the plays, he reaches for the infinitely elastic. His reading of The Tempest is representative: this is a script “the audience can experience in two ways, almost simultaneously, as a work of terrifying nihilism, beset by thunderbolts, as well as an enchanting poem, full of ‘sweet airs’.” It is, “at once, lyrical and brutal … and yet Arcadian and fantastical.” McCrum is all thunderous effusion with little discrimination. The problem plays are pesky, so The Merchant of Venice and Measure for Measure, with their taints of anti-Semitism and misogyny, are left out of the triumphant picture. He is not all that interested in the comedies either: major romances, including As You Like It and Much Ado About Nothing, are overlooked, while a short bit on Twelfth Night draws strained connections to Hamlet. Aside from a couple of sentences, McCrum doesn’t look at Shakespeare’s flops. It is the hits and nothing but the hits.

McCrum does mention one of my favorite Shakespeare plays, Timon of Athens, but it comes up in a scattershot chapter on the fortunes of the Bard in America. In Timon, “Shakespeare mirrors a quasi-American ambivalence towards capitalism: half celebrating and throwing parties; half hating the world and withdrawing into isolation.” What does this mean? People can treasure capitalism and hate the world. Profit and disdain often go hand in hand. Timon has rarely been produced in America, the land of optimism, because its key note is an exhilarating but morbid misanthropy. Worse is a bit on Othello that does not make much of an attempt to look at what the play means in the era of Black Lives Matter and #Me Too: “Othello’s mind spirals out of control as he gets caught up in a world without meaning, the prisoner of his identity, struggling to keep Desdemona.” A world without meaning? For Othello? For Iago? What would a Black critic make of calling Othello “a prisoner of his identity”? McCrum doesn’t bother to explicate: he tosses out inscrutable generalizations and gallops ahead. Novelist Graham Greene is quoted accusing the Bard of political conformity, and that raises a pertinent question — was the Bard a conservative? McCrum doesn’t offer a response, he just moves on (in the same paragraph!) to talk about Shakespeare and the plague. (The Bard mentioned pestilence here and there. But Ben Jonson directly dealt with the era’s pandemic in The Alchemist, even cracking a still amusing joke about social distancing.)

Shakespearean is at its best when it is dealing with concrete historical matters, chronicling how Shakespeare survived in a treacherous period. Interesting sections on the fortunes of the Earl of Essex and the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 provide an astute look at the ways that the Bard changed as an artist as he grew closer to court power and became a burgher. Still, even some of the volume’s speculation about the past falls short, with potted stuff about Shakespeare’s competition with Christopher Marlowe and the Bard’s reception in America. McCrum is also a bit gullible. He visits the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C. and accepts what he is told by a higher-up: “… especially in troubled times, members of Congress increase their visits to the Folger — ‘They feel that Shakespeare is somehow part of their story.'” Increase? Jim Jordan rolling up his sleeves to think long and hard about the ‘deep state’ as he thumbs through Julius Caesar? I don’t buy it … I want the names of the solons who regularly thumb through the First Folio.

McCrum tells us that he is a member of a long-standing Shakespeare lovers club, all-male until recently. Is it any surprise that the group’s favorite directors are all men (Deborah Warner anyone? Her 1989 RSC staging of Titus Andronicus was terrific.) As for the guys’ critical smarts, I have my reservations. At one point, we hear that the crew was struck agog when it heard Derek Jacobi’s King Lear whisper the line “Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow! You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout.” Of course, cutting against audience expectations is a venerable actor’s trick — Laurence Olivier was a master at lowering the volume so audiences were forced to lean in. It is a valuable lesson about modulation that those who think they must celebrate Shakespeare by cracking their cheeks would do well to heed.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of the Arts Fuse. For just about four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Just finished reading much better book on the qualities that make Shakespeare … Shakespeare. I would highly recommend Emma Smith’s This is Shakespeare (Pantheon Books, 2019). Her Bard is no “Merrie Ole England” saint or transcendent inventor of the human. This is an at times wobbly dramatist whose “plays are constitutionally incomplete .. their gappiness and their ambiguities produce creative readings. These radical uncertainties function as dramatic and intellectual cues to readers, playgoers and theatre-makers … Shakespeare’s characters, plots and unanswered questions provide space for us to think, interrogate and experience different potential outcomes. Shakespeare’s plays aren’t monuments to revere, or puzzles to resolve. They are partial, shifting, unstable survivals from a very different world which have the extraordinary ability to ventriloquize and stimulate our current concerns.” The Shakespeare we see reflects the Bard that we want.

Each of the academic’s 20 chapters (Smith is a professor of Shakespeare Studies at Oxford University) takes up a play, and there are some fascinating speculations here, particularly her discussion of the fear of incest in The Winter’s Tale and a surprisingly revelatory examination of the death of Cinna the poet in Julius Caesar. This is a scene that is often cut in performance. It shouldn’t be.

Smith is good at calling out instances of misogyny (Lady Macbeth), racism (Portia), and colonialism (Prospero). But why no mention of anti-semitism in her look at Merchant of Venice? Overall, though, this is a readable, fresh look at the plays that leaves you wanting more. For example, there’s no chapter on Timon of Athens, though Smith refers (tantalizingly) to its “satiric anti-heroism.” I yearn for This is Shakespeare II.