Opera Album Review: An Important Early Opera by the Composer of “Cavalleria Rusticana”

I felt at times that I was listening to the Italian equivalent of a Broadway musical, though a serious rather than jolly one.

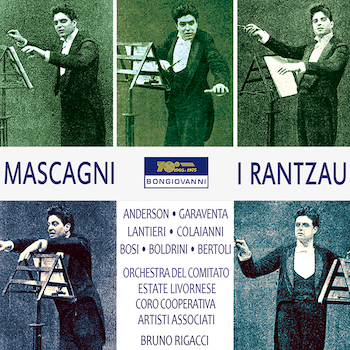

Pietro Mascagni: I Rantzau

Rita Lantieri (Luisa), Ottavio Garaventa (Giorgio), Domenico Colaianni (Fiorenzo), Barry Anderson (Gianni), Giacomo Boldrini (Giacomo)

Livorno Theater Orchestra, cond. Bruno Rigacci

Bongiovanni 2583-84 [2 CDs] 106 minutes

Mascagni’s operas fall into three basic categories. Cavalleria rusticana is performed everywhere and has been recorded dozens of times. Most of the others are performed and recorded occasionally, including L’amico Fritz. But only a few numbers from I Rantzau are ever heard. One of these is the overture. Another is the stirring Act 4 duet, in a collection sung by Scotto and Domingo, who get to join the full strings in a memorable tune such as Mascagni always knew how to write.

Here’s the entire opera, in a rerelease of its first and only recording, made during a performance in the Italian port city of Livorno in 1992. The recording was first released in 1995 but seems to have been little noticed. Michael Oliver, in Gramophone, panned it for its smallish orchestra and its second-rate singers, and for the patched-quilt lack of continuity in the plot.

Well, I’ve heard it now and enjoyed it. The plot is no worse than that of many other operas of the period. It involves two brothers (Gianni, baritone, and Giacomo, bass) who hate each other because of some dispute about an inheritance. Plus Gianni’s daughter Luisa and Giacomo’s son Giorgio, who of course love each other despite their fathers’ enmity. (I wish the three main male characters’ names didn’t all begin with G.)

There’s also a schoolmaster (Fiorenzo), who gives Luisa a chance to voice her sorrow that her father has been pressing her to marry Lebel — a minor member of the cast — who has the double advantage, for Gianni, of being the region’s prestigious “new commander” and of not being Giacomo’s son.

Act 2 ends with Gianni grabbing his daughter “with great violence” and nearly beating her but then stopping himself and running out. Violence is frequent in operas of the “verismo” period: in Act 3, Lebel challenges Giorgio to a duel over Luisa.

Fiorenzo again performs the dramatic functions of interlocutor and good conscience in scenes with Giorgio (Luisa’s beloved) and Gianni (her resistant father). Giacomo finally agrees to the young couple’s marrying if his hated brother (Gianni) will leave town forever. But Luisa refuses to sign the agreement, and Giacomo finally relents, freeing the young couple to marry. Schoolmaster Fiorenzo rips up the agreement, and the curtain falls.

There are spirited choruses along the way, and a fair amount of local color, such as little shepherd’s-pipe figures in the higher wind instruments, because we are in the Vosges mountains—the chain that is now in France but that, in Mascagni’s day, marked the boundary between France and Germany. I particularly enjoyed the music for winds and harp that opens Act 3 and that leads into a lovely chorus of women drawing water from the cool river stream as they sing of some “loving shepherd” who sends his kisses via the water “from far away.”

“I Rantzau” means “The Rantzau Family.” A town in Switzerland bears this name, as do some famous Germans. The title, in short, screams “north of Italy!” Scholars say that Mascagni was trying hard to create a work that would not resemble too closely his big hit, Cavalleria, which takes place among hotheaded people in Sicily.

But, not surprisingly, the touches of “northern-ness” cannot hide Mascagni’s gift for lovely and sometimes bouncing melody (whether in voices or orchestra), nor his basic directness of communication and his ability to write for solo voice or chorus glowingly or — in a sprightly chattering scene for the village women plus the schoolteacher — with conversational naturalness.

Composer Pietro Mascagni. Photo: Wiki Commons

The opera is very stop-and-go, and the audience complies by applauding enthusiastically after many musical numbers. They offer special appreciation after the splendid prelude to the final act. (It is called, as usual in verismo operas, an “intermezzo.”) But the work is also very compact: a prayer by the men’s chorus for God to protect them “in the dark of night” lasts under a minute. And all four acts are over in less than an hour and three quarters.

Fortunately, the performance oozes commitment. The singers are reliably on pitch and do not wobble more than do many that we hear today on Met broadcasts. The chorus is a little off-pitch in the short church hymn; I suspect that the small organ or harmonium—placed in the wings?—was hard for the chorus members to hear.

The cast members seem to care intensely about what they’re singing about. It surely helps that they are all native Italian-speakers, except the baritone brother, Barry Anderson (perhaps Australian? — I see that he performed often in Adelaide). The recorded sound is clear but shallow and unresonant. Almost like a good 1950s mono recording, but in stereo. The applause at the ends of acts fades out quickly, which is fine by me.

I felt at times that I was listening to the Italian equivalent of a Broadway musical, though a serious rather than jolly one. Everybody is in the spirit of the thing — there’s no sense here of a “serious work of art” imported from some distant and different land. This is a nearly pure Italian cultural product, though of course shaped by various pan-European musical and theatrical traditions (such as the Sardou type of French theatrical gritty “realism”).

If you like this kind of thing, you’ll like this kind of thing. I liked it. I welcome it back into the catalogue, and into the big second category of Mascagni operas that are not unknown but deserve to be heard and seen more often. Several of the arias and soliloquies could work well in a vocal recital, especially if the audience were given the words and a good translation. The whole recording is available through Spotify and other streaming services. Selected tracks can be heard for free on YouTube.

The booklet contains an informative essay and the full libretto. Both are also given in inept translations that nonetheless are more or less comprehensible, once you figure out certain confusing typos such as “world” for “word.”

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Cavalleria Rusticana, Livorno Theater Orchestra, Pietro Mascagni

I know a Barry Anderson from Milano, Italia. We sang together on numerous occasions. A baritone. Is this the same Barry? Also, I worked with Bruno Rigaci in Philadelphia, PA., U.S.A. We did a Gianni Schicchi together with Capobianco. Surprised to see both names in print. Wonderful performers.

Renee-Michele Evans Sasson