Book Review: “Seeing Sideways” — Parenting on the Edge

By Chelsea Spear

Those who have followed Throwing Muses’ Kristin Hersh’s career over the past three decades are the target audience for this memoir. But she is a good enough writer to interest people who may never have listened to her music.

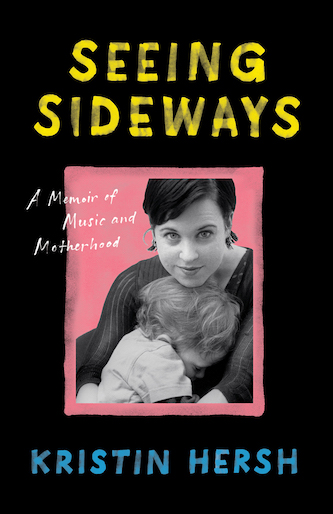

Seeing Sideways: A Memoir of Music and Motherhood by Kristin Hersh. University of Texas Press, 280 pages, $27.95

Over the past decade, Throwing Muses bandleader and singer/songwriter Kristin Hersh has developed a side career as alternative rock’s first lady of letters. She chronicled her experiences as a teenage rock-star-in-training, expectant mother, and person experiencing mental illness in her first book, Rat Girl. Don’t Suck, Don’t Die eulogized her friend and peer Vic Chestnutt. In Seeing Sideways, Hersh writes at length about the most important role she’s taken on: that of mother to Doony, Ryder, Wyatt, and Bodhi.

Seeing Sideways is divided into four parts, each section devoted to the early childhood of one of her sons. While other characters pass through the book — from her former spouse and her bandmates to lifeguards, cops, listeners, and fans — the only figures she refers to by name are her sons. At first, this is a bit confusing; I made a list on the back of the dust cover to keep track of some recurring characters. By only naming her sons, though, Hersh maintains a sharp focus on their growth and development and makes sure our eyes are as trained on them as hers are.

The infancy of Hersh’s youngest son, Doony, coincided with the early years of Throwing Muses’ major-label tenure. Doony’s father believes that Hersh’s job as a musician and her diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder make her an unfit mother. He ends up with full custody of their son. Hersh details the immediate and long-lasting effects on her of the court battle for custody, which made the Providence media in the late ’80s. The refrain “there is a cop standing on the front porch. There is always a cop standing on the front porch” threads throughout Seeing Sideways. An empty child’s car seat serves as a symbolic image of her PTSD. In 2021, given the nation-wide debates about police overreach and the broken criminal justice system, Hersh’s long struggle with the legal system sounds a shamefully contemporary note.

Some of the book’s sunnier passages give a more nuanced idea of Hersh’s parenting style than a 1995 Rolling Stone profile (viz: “Hersh, an ideal mom if there ever was one, asks her children with a mischievous smile, ‘Would you like some soda with your candy?’”). Even when on arduous press tours, she listens to her children and helps them explore their interests. In the chapter on her next-youngest son Wyatt, she describes who watching him draw steadies her as she conducts interviews with the British press. That said, Hersh’s nurturing instincts can backfire in darkly humorous ways. Here is her response to her son Bodhi’s early attempts to swim with sharks: “I caught him in the air, his tiny, round sneakers over the surface of the shark-filled water, and turned him around to face me. Eye to eye, we studied each other. We’re going to the butterfly room.”

Throughout her career, Hersh has been crystal clear about her well-considered disgust with the record industry. Her misadventures dealing with the glamorous side of the music industry serves as a sort of subplot in the first half of the book. The cacophonous independence of Throwing Muses doesn’t sit well with the publicity department at their record label, who speaks condescendingly to Hersh about how to market the band: “I won’t know what outlets to go after until we determine a target audience. There’s a big word for it: ‘demographic’.” She expresses her discomfort with the label pursuit of trend-following “fans” the label pursues — “they were people who liked to like, and liked what others like…They want to put you on a pedestal so they can knock you down.” Still, when she leaves the business types, she connects with “listeners” who are invested in her music. At one point Throwing Muses’ tour bus caught on fire and Hersh contemplated cancelling their tour. But “by the time we got to the club, word had gotten out that we’d lost our bus and the club’d been inundated with calls from people asking how they could help.”

Hersh draws on words from her songs to string together stories about her children, which provides a small but revealing window on her creative process. Her lyrics can sometimes have the random quality of filling a melody with a string of syllables and vowel sounds. But knowing that the line “I cut lemons and lemons and limes” was inspired by her sons’ attempts to eat sour citrus from a tree in her backyard suggests how her life informs her work. Similarly, seeing Hersh’s lyrics quoted alongside her thoughts about pivotal relationships — the end of her marriage and slow courtship of a man she knew since she was a teenager — gives those songs an even greater undercurrent of sadness and anger.

As in her previous books, Seeing Sideways is written in an elliptical, poetic style that makes it easy for readers to become caught up in her stories, even when they become heartbreakingly violent. Hersh blunts the melancholy and pain with her mordant sense of humor, at times drawing on amusing images to cut her confession’s hurtful edge.

Obviously, those who have followed Hersh’s career over the past three decades are the target audience for Seeing Sideways. But she is a good enough writer to interest people who may never have listened to her music. The astringent survivor’s wisdom that runs through Seeing Sideways will be of value to parents of unconventional children and as well as those struggling with mental illness.

Chelsea Spear has written for the Brattle Theatre’s Film Notes blog, the Gay & Lesbian Review, and Crooked Marquee. She lives in Boston.