Book Review: “Refugee: A Memoir” — A Powerful Story of the Plight of Millions

By David Mehegan

Refugee: A Memoir was not written to entertain but to outrage and activate.

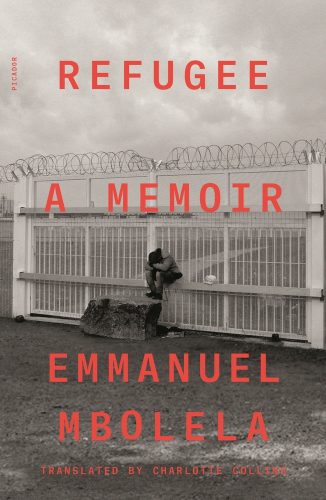

Refugee: A Memoir by Emmanuel Mbolela. Farrar Straus & Giroux. Translated, from the German, by Charlotte Collins, 236 pp. $28.

The dusty or sodden roads and heaving seas are full of desperate pilgrims, carrying small children or old people and what they can carry, pushing wheelchairs or market baskets from the southern hemisphere, looking for shelter and hope in the developed parts of the world. We see their forlorn faces on the nightly news, lined up in flashlight at our own border by the Border Patrol, or bodies packed shoulder to shoulder in Zodiac-type rafts supplied by traffickers at the cost of the migrants’ last pennies — all too often pathetically overturned — on the Mediterranean Sea.

We seldom read their complete stories in their own words, except in brief answers to journalists’ questions on rescue ships or in refugee camps. Thus the value of Congolese activist Emmanuel Mbolela’s comprehensive 2014 account, Refugee: A Memoir, originally published in German and now (with some updating) in English.

The migrants come from sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, to North Africa or the Balkan countries, determined to make their way to Europe. Or they migrate north, east, or west to Central America, thence to join the wretched of the Honduras/El Salvador/Guatemala triangle as they flow fitfully north toward the U.S./Mexico border. They used to be called refugees, historically the spawn of war. Notwithstanding Mbolela’s title, today more often they are referred to, in English at least, simply as migrants. Sometimes they still are victims of war, but as often they are fleeing organized crime, official corruption and police brutality, or unendurable poverty from drought or loss of any possible means of livelihood.

Mbolela’s personal story is unusual. Now in his late forties, he was born to a middle-class family in DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo). He was earning a degree in economics in the late ’90s when he became politically active against the dictators Mobutu Sese Seko and his successors, Laurent-Désiré and Joseph Kabila. Amid violent repression of the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), the main opposition party, Mbolela was forced to flee the country in 2002. A fitful two-year journey followed, through Cameroon, Nigeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali, Algeria, and finally Morocco. In 2005, he founded an organization called ARCOM, the Association for Congolese Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Morocco, to advocate for the rights and interests of undocumented migrants. In 2008, he was allowed to enter the Netherlands, where apparently he still lives.

The detailed account of Mbolela’s trek (he calls it an odyssey, though it leads away from home) includes the terrible fate of many who were with him, from various countries. What they all want desperately is to reach Europe, where they think they will at least be safe from attack and murder. In these cruel badlands at the outskirts of countries, traveling women are flagrantly raped and abused at the hands of traffickers, who also demand every bit of money from the defenseless travelers at every step of the way. Mbolela is one of the lucky ones in that at various stages he is saved from disaster by money wired by his family. He does what little he can to help his fellow travelers, but is usually powerless.

In the desert town of Tinzaouten, Algeria, refugees were segregated into ethnic groups called ghettos with a de facto boss called a chairman. “Yet again,” Mbolela writes in a characteristic tone of outrage, “I witnessed the violence to which women traveling in these regions are subjected. Young women from Nigeria were particularly badly affected. Members of their own community would sexually abuse them and sell them to people from other ghettos for money. The money from these transactions went directly to the chairman. … They were mercilessly abused, forced to live in degrading conditions, and exposed to a high risk of infection. I was shocked to see underage girls in the Nigerian ghetto who were pregnant. I remember one of these young women, heavily pregnant, who kept vomiting. In what circumstances would she have to give birth?”

One young friend, a Congolese, was determined to get to Libya and to make the water crossing to Italy. Mbelela himself had considered doing so but had been warned against it on account of the danger. “Later,” he writes, “we heard from our Congolese friends in Libya that the boat he was on had capsized, and he had drowned. Dead — after all the torments he had endured, far from his parents, who may never even have heard what happened to him. May his soul rest in peace!”

Mbolela had attended Catholic schools as a boy, and his religious outlook shows through lightly (as in the quote above), but not in any proselytizing way. His political views likewise are humane, idealistic, and democratic — he hates corruption, cruelty, greed, and the abuse of the weak by the strong, which he sees as rampant in the politics of Africa. And yet much of that he blames on Europe, on the old colonizers and present-day enablers of the dictators. “No African dictator can remain in power for long without the support of the West,” he writes. “This has been my consistent message at every conference I’ve spoken at these last five years.”

Mbolela’s view as to what should be done runs more toward the policy of European than of African societies. He sees the slamming of the doors of Europe as a cruel injustice. Unless I missed it, he never refers to the United States or U.S. immigration policy, but denounces the “externalization” of European borders; that is, the policy of trying to discourage the wretched of the earth from leaving their own countries. This would seem also to apply to Vice President Harris’s June 8 warning to potential migrants in Guatemala: “Don’t come.” Harris was speaking of the danger of the road, to be sure, but also of U.S. laws that prevent unrestricted access to the country.

From Mbolela’s perspective, those like himself who are forced to flee oppression, violence, or poverty in their home countries have a natural right to travel to safety in Europe, if that is where they mean to go. He quotes approvingly a 2005 speech by a fellow Congolese migrant, trapped as he was without documents or legal rights. “It’s almost impossible for refugees and migrants to integrate in Morocco,” she said. “I am convinced that the Earth belongs to all people, and that there should be no borders. I know that I have the right seek a country that will give me asylum.”

Emmanuel Mbolela.in 2019. Photo: Facebook.

Right or not, this position, which Mbolela clearly shares, runs counter to the reality of virtually every country’s sense of sovereignty: No country in today’s world proclaims, “Come on in — everyone’s welcome.” As we see in the Mediterranean and on our own southern border, the attempt by migrants to force their way in, or to place their fate in the hands of unscrupulous traffickers, has had tragic outcome for many. And the misrule of petty dictators in Africa cannot be blamed entirely on Europe. If that were so, Mbolela would not still be hopeful of domestic political reform in Congo.

Finally safe in the Netherlands, over time Mbolela became a spokesman and advocate for the rights of the dispossessed, a sought-after speaker in the manner of our own Frederick Douglass. He has organized more than four hundred conferences on the plight of international migrants since this book was first published. With this English translation, his influence is bound to spread.

Few readers will have an interest in the text’s history, but I was curious about one question: In what language was it written, and why is that not disclosed? We are told that the book was first published by Verlag, in German, in 2014. The copyright page reports that the English edition is “translated by Charlotte Collins from the German translation by Alexander Behr.” Mbolela speaks French (at one point in the book, he gives French lessons), and at least two Congolese tongues, and at least studied Dutch in the Netherlands. Unless Behr is conversant with Congolese languages, it seems most probable that the book was composed in French. However, a preface discloses that “it appeared in French in January 2016, and in Italian in 2018.” Was the French edition, two years after the German, the original text from Mbolela’s hand? or was it translated back from Behr’s German?

If Refugee is a translation of a translation, that might account for its somewhat “as-told-to” flavor. It reads more like speech than written discourse, with a direct, plain character but also a certain woodenness. Not that this is important, given the subject. It was not written to entertain but to outrage and activate. I recall asking more than one book reviewer who had waxed eloquent but taken no clear position, “So, do we like this book?” But a cri de coeur such as this, which has to be written, which busts out of irrepressible outrage, has a way of seeming to transcend criticism. The pain, passion, and frustration of Mbolela’s journey, and the plight of the millions like him, are manifest, as he intended, and that may be all that matters

David Mehegan is the former book review editor, and writer on books, authors, and publishing, of the Boston Globe.

Tagged: Africa, Charlotte Collins., David Mehegan, Emmanuel Mbolela, immigrants