Jazz Special Feature: Chick Corea (1941-2021) — Memories and Impressions

By David Daniel, Steve Elman, Steve Feeney, Tim Jackson, Allen Michie, Milo Miles, Steve Provizer, Paul Robicheau, Evelyn Rosenthal, Jason M. Rubin, and Michael Ullman

Arts Fuse critics pay homage to Chick Corea performances and recordings that they found memorable.

Steve Elman — Introduction and overview of Chick Corea’s career

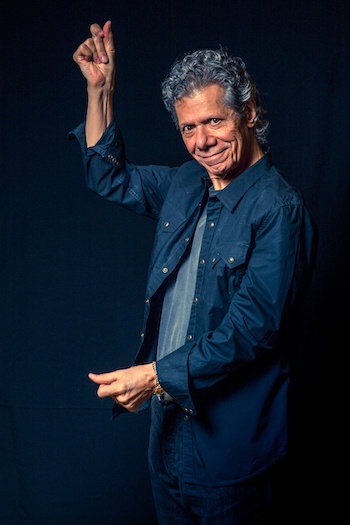

The late Chick Corea. Photo: Mikoaj Rutkowski.

Armando Anthony Corea, a keyboard virtuoso by any standard, worked in at least 14 different areas of musical specialization, with many of their edges blurred by cross-fertilization. No matter what the genre, he excelled. He was one of the most versatile musicians of all time.

I’ve asked my colleagues at the Arts Fuse to contribute some words about Chick Corea performances and recordings that are particularly memorable to them. I’ve supplemented their comments with some links to previous Fuse posts about Corea’s work. What you’ll read below and in those earlier posts demonstrate the rich breadth of Corea’s talent and the remarkable impact he had on a wide range of listeners.

Notable recordings. (This is not even an attempt at a complete discography!)

Latin jazz (1962-67) Early work, capitalizing on Corea’s supposed Latin heritage (actually, he was Italian-American), with Mongo Santamaria, Herbie Mann, Cal Tjader, etc.

Session pianist (1964-98) Straight-ahead (mostly) acoustic jazz, building on the legacies and styles of Bill Evans and Herbie Hancock, with a distinct influence of Red Garland. There were significant sessions with Hubert Laws (1964-72), Blue Mitchell (1964-66), Dizzy Gillespie (1967) Pete LaRoca (1967), Donald Byrd (1967), Bobby Hutcherson (1968), Eric Kloss (1969-1970), Richard Davis (1971), Joe Farrell (1970-71), Elvin Jones (1971), Stan Getz (Corea was a vital element in one of Getz’s greatest recordings, Sweet Rain [Verve, 1972]), Ron Carter (1979) and Joe Henderson (1979-80).

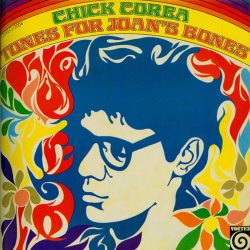

Adventurous post-bop (1966-69) Acoustic recordings spotlighting Corea’s early composing, with modal harmonies, open structures, and free interplay: Tones for Joan’s Bones (Vortex, 1966) with Woody Shaw, Joe Farrell; Is (Solid State, 1969) and Sundance (Groove Merchant, 1969) with Woody Shaw, Bennie Maupin, Hubert Laws.

Traditional piano trio (1968-2018) The classic form of the jazz trio, with acoustic bass and drums, interpreted in a wide variety of ways. (Properly speaking, the Circle trio material below belongs to his avant-garde period.) Now He Sings, Now He Sobs (Blue Note, 1968) was Corea’s first in the trio format, with Miroslav Vitous and Roy Haynes, straddling traditional and more adventurous music; more music from the same session appeared on Circling In (Blue Note, 1975). In 1981, the same trio recorded Trio Music (ECM), a two-disc set split between open improvisations and compositions by Thelonious Monk; Trio Music Live in Europe (ECM, 1984) brought the same trio back for more traditional repertoire. Corea revived the concept in the Akoustic Band (1989) with John Pattitucci and Dave Weckl. Avishai Cohen and Jeff Ballard were his partners on Past, Present and Futures (Stretch, 2000). Later recordings include sessions in 2009 with Stanley Clarke and Lenny White, his former partners in Return to Forever; in 2010 with Eddie Gomez and Paul Motian, in memory of Bill Evans; Trilogy (with Christian McBride and Brian Blade) in 2013 and 2018; and in September 2018, a memorable week-long stand in Boston at Scullers by his Vigilette Trio, with Carlitos del Puerto and Marcus Gilmore, his last Boston-area appearance (captured by WGBH [link: https://www.wgbh.org/jazz/2018/11/01/chick-corea-vigilette])

Fusion with Miles Davis (1968-70) Proto-fusion and ultimately avant-fusion, in groundbreaking sessions that produced Filles de Kilimanjaro (Columbia, 1969), In a Silent Way (Columbia, 1969), Bitches Brew (Columbia, 1970) and Miles Davis at Fillmore (Columbia, 1970). Since Davis’s death, extensive Columbia Legacy boxed sets have brought to market all of the complete takes from the studio sessions of the time; Corea appears on The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions (1998), The Complete In a Silent Way Sessions (2001), and The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions (2003). Recently, live performances by the Davis group with Corea from these years have been added to the discography.

Circle (1970-71) A cooperative avant-garde trio/quartet, with Anthony Braxton, Dave Holland, and Barry Altschul. The original trio LPs were The Song of Singing (Blue Note, 1970) and A.R.C. (ECM, 1971). Braxton joined them for Paris-Concert (ECM, 1971). Unreleased material from the same period was issued in two Blue Note double-LP sets, Circling In (1975) and Circulus (1978). Additional performances by the group in 1970 and 1971 were issued by Stretch (Circle 1: Live in Germany Concert, 1996 and Circle 2: Gathering, 1996)

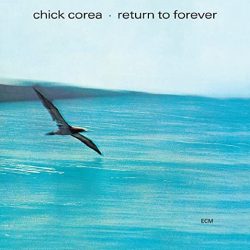

Return to Forever I & III (1972-73 & 1977) The vocal editions, both of which featured Joe Farrell on saxes and flute. Flora Purim sang on the 1972 recordings, with Stanley Clarke and Airto Moreira, and they brought some of Corea’s most enduring tunes into the world — “La Fiesta,” “Spain,” and “500 Miles High.” Gayle Moran sang on Musicmagic (1977), with a large studio ensemble that included Farrell.

Return to Forever I & III (1972-73 & 1977) The vocal editions, both of which featured Joe Farrell on saxes and flute. Flora Purim sang on the 1972 recordings, with Stanley Clarke and Airto Moreira, and they brought some of Corea’s most enduring tunes into the world — “La Fiesta,” “Spain,” and “500 Miles High.” Gayle Moran sang on Musicmagic (1977), with a large studio ensemble that included Farrell.

Return to Forever II (1973-76) The electric edition, with Bill Connors, Al DiMeola, or Frank Gambale on guitar. The new band retained the core of RTF I, Clarke on bass, with new stalwart Lenny White on drums.

Mass-appeal recordings using contemporary studio production (1976-80) My Spanish Heart and The Leprechaun (both Polydor, 1976), The Mad Hatter (Polydor, 1977), Secret Agent (Polydor, 1978), Tap Step (Warner Brothers,1980)

Elektric Band (1986-91) with Eric Marienthal, Frank Gambale, and Carlos Rios. John Pattitucci and Dave Weckl, the rhythm section, moved from fusion to more typical jazz playing when Corea created his Akoustic Band trio.

Solo acoustic piano This format allowed Corea maximum freedom to explore standard repertoire and spontaneous composition. His first album of solo piano (Piano Improvisations, Vol. 1) was released in 1971 on ECM. Other solo sessions followed in 1978, 1983, 1994, 1999, and 2014. 2020 saw his last solo release to date, Chick Corea Plays (Concord Jazz), a collection of live concert excerpts with extensive spoken introductions, ranging from Mozart and Scarlatti to spontaneous four-hand improvisations with two volunteer pianists from the audience.

Duets His enduring partnership with vibraphonist Gary Burton was documented in recordings from 1972, 1978, 1979, 1997, 2001, 2007, and 2012. Other duo collaborations included sessions with Herbie Hancock, Makoto Ozone, Friedrich Gulda, Nicolas Economou, Bobby McFerrin, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Béla Fleck, and Stefano Bollani.

Later cooperative groups (1981-2013) The Three Quartets Band (1981) with Michael Brecker; Touchstone (1982), exploring flamenco, with Paco DeLucía; Like Minds (1997) with Gary Burton and Pat Metheny; Origin (1998-99) with Steve Davis, Steve Wilson, Bob Sheppard; the Remembering Bud Powell Band (1997-2001) with Terence Blanchard, Joshua Redman; the Five Peace Band (2009) with John McLaughlin; The Vigil (2013), an update of sorts of Return to Forever, with Tim Garland and Charles Altura.

Formal compositions, including performances of classical repertoire and his own works combining through-composition and improvisation.

– Lyric Sextet (ECM, 1982), with Gary Burton and string quartet

– Bartok: Pieces from Mikrokosmos (Nos. 69, 113, 123, 127, 135 & 146), with Nicolaus Economou (from On Two Pianos, Deutsche Grammophon, 1983)

– Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466 / Piano Concerto No. 23 in A, K. 488 (The Mozart Sessions, Sony Masterworks, 1996), with the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Bobby McFerrin

– Corea: Piano Concerto No. 1 / Spain, for sextet and orchestra (Corea.Concerto, Sony Masterworks, 1999), with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Corea and Steven Mercurio

– Mozart: Two-Piano Concerto in E-flat, K. 365 (Teldec, 2009), with Friedrich Gulda and the Concertgebouw Orchestra, conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt

– Corea: The Continents, for jazz quintet and orchestra (Deutsche Grammophon, 2012), with Corea’s working group, the Imani Winds, the Harlem Quartet, and orchestral musicians from the New York City area, conducted by Steven Mercurio

At the 2019 Das Zelt Musik Festival in Freiburg im Breisgau. Photo: Wiki Commons.

A career-retrospective celebration of his 70th birthday in 2017 The Musician (Concord Jazz, 2017) documents a month-long run at the Blue Note in New York in 2011, where he performed with a kaleidoscope of guest artists, offering new perspectives on every aspect of his work. The all-star cast included Gary Burton, Stanley Clarke, Jack DeJohnette, Herbie Hancock, Gayle Moran, Bobby McFerrin, John McLaughlin, Marcus Roberts, and Wallace Roney.

With Miles Davis, 1969-70

Steve Provizer on Corea and Herbie Hancock with Miles at the Jazz Workshop, October 1969.

In the late 1960s, Miles Davis innovated the idea of using two keyboardists. Chick Corea was his mainstay, but Herbie Hancock, Joe Zawinul, and Wynton Kelly all cycled through the group. The recording sessions in November 1969 that produced Big Fun (Columbia, 1974) and The Complete Bitches Brew Sessions (Columbia Legacy, 1998) used Corea and Hancock, but there are no live recordings or gig listings from this period with Chick and Herbie both playing.

However, when I went to see Miles’s band sometime during their run from October 13 to 19, 1969, at Boston’s Jazz Workshop, Chick and Herbie were both on the stand. With them were Wayne Shorter on reeds, Dave Holland on bass, and Jack DeJohnette on drums. This was an unusual, possibly one-time, configuration in live performance.

The record that finally branded Miles’s new direction — Bitches Brew (Columbia, 1970) — had yet to be released, but by this point I’d heard Filles de Kilimanjaro (Columbia, 1968) and In a Silent Way (Columbia, 1969), released earlier that year. I loved Filles, but not Silent Way, which was wider open, less “composed,” and farther down the road towards Bitches Brew. I was adapting slowly, but the earlier acoustic music of Miles still dominated my thoughts as I walked into the Workshop. I soon found that my usual touchstones of technical musical analysis were not useful guideposts. I was caught up in the current of the music — sometimes able to float, sometimes struggling for breath.

There are a few specific things that stick out in my memory of the concert (aside from hitchhiking into town and having to panhandle to make the $15 ticket price). The first is that Miles played very little. Occasionally he’d pop on stage to play a phrase to trigger the band —an introduction, transition, or ending — but I remember only a few brief-ish solos. The rest of the time he was lurking onstage and off, always listening carefully to the band.

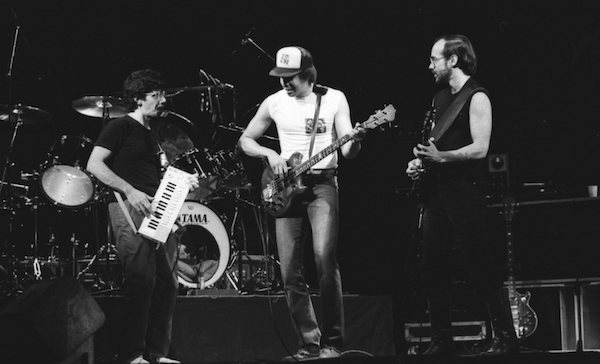

Return to Forever at the Boston Opera House, 1983. Photo: Paul Robicheau.

The second thing that stayed with me was Chick’s presence. I had never seen anyone play with antennae up that high. The entire band seemed to be conscious of exploring terra incognita, but Chick was like a tuning fork, prepared to pick up the resonances in the air and translate them through his body — that is, the piano. He and Herbie were like two kids at play, pulling each other into corners, posing questions, pushing each other into jeopardy and, ultimately, saving each other from falling over the precipice.

I also remember the staunch yet light dancing sound of Holland’s bass, which I also heard in DeJohnette’s drums. Shorter carried the horn-playing burden with mastery, adapting his compositional approach to solos into this new zone of exploration.

Chick Corea has been quoted as describing the kind of music I heard that night as “that thing of vaporizing themes and just going places.” It was all that, and it was a portent of much to come.

Steve Elman on other Davis releases that offer additional perspective.

As Steve Provizer notes, when Corea worked in the studio with Miles, he usually was a part of ensembles with two (sometimes three) keyboards. However, he was the only keyboardist in the Davis working band from mid-1969 until mid-1970, with some exceptions, like the Workshop gig. Releases of live performances from this period never came to market until 2011. Since then, four CD sets permit us to hear what Corea did with Miles when he had the keyboards to himself. Live in Europe 1969: The Bootleg Series Vol. 2 (Columbia Legacy; rec. July – November 1969, released 2013) offers a few very free interpretations of older material (“Milestones,” “Footprints,” and “’Round Midnight”) and contemporary originals. The newer, more abstract approach of the group dominates everything, even the standbys. (For example, Corea’s solo on “’Round Midnight” is pure burn; he never touches Monk’s harmonic foundation or the theme’s original melancholy.) Corea has a strong hand in pushing the intensity of the band throughout, with Tony Williams stoking the fire with the fervor he would soon be employing in his own band, Lifetime.

Jack DeJohnette replaces Williams on drums for Bitches Brew Live (Columbia Legacy; rec. July 1969, released 2011), The Lost Quintet (Sleepy Night; rec. November 1969, released 2020), and the three tracks recorded at Fillmore West released on Miles at Fillmore (Columbia Legacy; rec. April 1970, released 2014). These recordings document some of the most adventurous avant-fusion Davis ever played. Corea and Holland (on acoustic bass in all four of these releases) are already pushing toward the free interplay they would explore in Circle, and their work together in this electric context has the additional impact of volume and intentional distortion, with Corea sometimes deploying a ring modulator. By August 1970, as documented in the Isle of Wight show and Tanglewood concerts (viewable on YouTube) the direction of the Davis band shifted towards funk, and Keith Jarrett took the dominant role on keyboards.

Circle (Trio and Quartet), 1970-71

Steve Feeney on A.R.C. (ECM, 1971).

It doesn’t seem right that we won’t have Chick Corea around anymore. Even if you didn’t like the direction he was taking at any particular time, his music always powered an important energy field on the scene. Shortly after he left Miles, he made recordings for the nascent ECM label that were very appealing to those who believed there was something left to say in jazz without amplifiers.

It doesn’t seem right that we won’t have Chick Corea around anymore. Even if you didn’t like the direction he was taking at any particular time, his music always powered an important energy field on the scene. Shortly after he left Miles, he made recordings for the nascent ECM label that were very appealing to those who believed there was something left to say in jazz without amplifiers.

A.R.C. partners Corea with Dave Holland on bass, and Barry Altschul on drums. The threesome had released one album previously, and Holland and Corea had made history when they joined up with Miles Davis on his first electric excursions. A.R.C. starts off with a version of Wayne Shorter’s “Nefertiti,” a tune familiar to the pianist and bassist from their time touring with composer/saxophonist Wayne Shorter and Davis. On the title track and beyond, the three let a furtive lyricism flavor just enough of their free-jazz onslaughts to make you want to lean way in.

Corea intermittently excelled in acoustic trio settings over the years that followed. But his work was never more challenging or rewarding than in the early collaborations with Holland and Altschul.

Steve Elman notes:

The intuitive rapport Corea established with Dave Holland and Barry Altschul in Circle’s trio incarnation reached a free-jazz pinnacle when saxophonist Anthony Braxton joined them and added his compositions to the band’s book.

David Daniel on Paris-Concert (ECM, 1971).

After I got out of the Army, in the early 1970s, with no job and even less ambition, I spent a lot of time listening to music. There were a handful of albums that became a kind of lifeline back into the world for me — Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On (Tamla, 1971), certainly, and King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King (Island, 1969). Also in the rotation was Paris-Concert (ECM, 1971), a live recording by Circle that I picked up in a used-record store on Boylston Street. In my mostly rock and R&B line-up, Paris-Concert was a decided outlier.

I had enjoyed some early Miles Davis, but I never connected with his electric stuff, where Chick Corea was a sideman; I found Bitches Brew (Columbia, 1970) unlistenable. I should also add that later I followed saxophonist Anthony Braxton, trying, with minimal success, to make sense out of his complex musical illustrations.

But to circle back — Circle was something else.

In ways, “Nefertiti” and “No Greater Love” from Paris-Quartet remain on my mental playlist of that period, every bit as much as “Mercy Mercy Me” and “21st Century Schizoid Man.” The quartet offered long, often oblique jams, with each of the musicians contributing ideas. About all I knew of Corea at the time was that he was Chelsea-born; being a Boston kid myself, that made us homeboys. And maybe for that reason I listened extra closely to his keyboard.

In time, of course, as Corea’s work expanded outward and earned him ever more exposure and plaudits, he got as close to being a household name as any jazz musician ever gets. I’ve liked some of his work, and have felt little connection with some, and there’s a lot I’ve not yet heard. But when he was good, as he is here, in combo with Braxton, Holland, and Altschul, he was great. So, these words are paying back a debt.

Return to Forever I & III (1972-73 & 1977)

Evelyn Rosenthal on Return to Forever (ECM, 1972, with US release in 1975) and Light as a Feather (Polydor, 1973): the singable Chick.

Even before my first jazz singing stint around Boston and Cambridge in the late 1970s to early ’80s, I was always a sucker for jazz with vocals — and not just the greats (Ella, Sarah, Billie) singing the greats (Porter, Arlen, Gershwin, et al.).

I also loved the vocalese masters who put words and scat syllables to tunes and solos by the likes of Parker, Coltrane, Herbie Hancock, and Wayne Shorter that originated as instrumental performances. Classic recordings by Lambert, Hendricks, and Ross (and, later, Bavan) led to albums like Mark Murphy Sings (1975), where Murphy’s vocals give new perspective to Coltrane’s “Naima,” Freddie Hubbard’s “Red Clay,” and Hancock’s “Cantaloupe Island.”

But before 1970 or so, there were few examples of serious work by bona fide jazz composers with vocals, much less original tunes with actual lyrics. Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, and (in one memorable session with Sheila Jordan) George Russell did it, but few others tried. So Chick Corea was almost setting a new standard when he formed his project Return to Forever in 1971.

That first edition of the group rested on Stanley Clarke’s bass, and Clarke would be the one constant in the subsequent editions. Joe Farrell’s flute and saxes had been part of Corea’s groups on earlier recordings. But the distinctive character of the first RTF came from percussion and drums by Airto Moreira, Corea’s former bandmate from Miles Davis days, and the vocals of the adventurous singer Flora Purim, Moreira’s wife and fellow Brazilian. The first two RTF albums with Flora and Airto were touchstones for real integration of jazz with the distinctive qualities of Brazilian music, going well beyond bossa nova. With their appealing — even catchy — melodies and rhythms, those two recordings pointed a direction away from Corea’s earlier work in traditional and avant-garde settings toward “a music that would communicate and be felt and understood by people of all types” (as Corea said on the cover of my LP copy of the US edition of Return to Forever).

That first session, recorded in 1972, was not released in the US until 1975, although Corea fans easily got hold of copies of the German import version on ECM. But many here did not hear it until after 1973’s Light as a Feather had scored with songs like “500 Miles High” and “Spain,” which quickly joined the ranks of jazz standards. Some of Corea’s compositions on both LPs showed Spanish influences: the intro to “Spain” echoes Joaquín Rodrigo’s “Concierto de Aranjuez” (which had been reimagined by Miles Davis and Gil Evans on “Sketches of Spain”), and a section of the Andalusian folksong “El Vito” pops up in “La Fiesta.” Samba rhythms abound, in “Return to Forever,” “Sometime Ago,” and “What Game Shall We Play Today” on Return to Forever, and “You’re Everything,” “Captain Marvel,” “500 Miles High,” and “Spain,” on Light as a Feather — though “Spain”’s flamenco roots are equally apparent, handclaps and all.

That first session, recorded in 1972, was not released in the US until 1975, although Corea fans easily got hold of copies of the German import version on ECM. But many here did not hear it until after 1973’s Light as a Feather had scored with songs like “500 Miles High” and “Spain,” which quickly joined the ranks of jazz standards. Some of Corea’s compositions on both LPs showed Spanish influences: the intro to “Spain” echoes Joaquín Rodrigo’s “Concierto de Aranjuez” (which had been reimagined by Miles Davis and Gil Evans on “Sketches of Spain”), and a section of the Andalusian folksong “El Vito” pops up in “La Fiesta.” Samba rhythms abound, in “Return to Forever,” “Sometime Ago,” and “What Game Shall We Play Today” on Return to Forever, and “You’re Everything,” “Captain Marvel,” “500 Miles High,” and “Spain,” on Light as a Feather — though “Spain”’s flamenco roots are equally apparent, handclaps and all.

Flora’s elastic voice and charming Brazilian-accented English fly throughout both albums, whether singing Neville Potter’s lyrics, or wordlessly doubling and harmonizing. Some of the lyrics were a little goofy and New Age-y, influenced by the band’s flirtation with Scientology (“Look around you my people / If you look then you will see / How to love/ Life is paradise all together / What game shall we play today?”), but the melodies and rhythms made you want to sing along — and, for me, to add the tunes to my repertoire. The lovely release on “500 Miles High,” the roller coaster intervals on “You’re Everything,” and especially the challenging staccato melody and rhythm on the handclap portion of “Spain” — these were singer magnets. By 1980, the great Al Jarreau opened another tune to vocalists by providing lyrics to “Spain” on his album This Time (Warner, 1980).

On behalf of jazz singers everywhere, thank you, Chick, for these incomparable recordings and compositions that celebrate the voice’s place in jazz.

Return to Forever II (1973-76)

Tim Jackson on “Captain Señor Mouse” from Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy (Polydor, 1973).

Where to start with Chick Corea’s genius? The one song I listened to a hundred times is “Captain Señor Mouse.” It hums along furiously over the perpetual motion of Stanley Clarke’s throbbing bass line and Lenny White’s relentless Latin-Fusion rhythms. The arrangement seems to come apart, then power back, only to drift into elegiac themes and then roar into a thundering whole. Chick plays lilting melodies or comps for Bill Connors’s soaring guitar by stabbing out simple syncopated rhythms. After again swooping into the stratosphere, they suddenly all reconnect to the form.

I saw Corea perform the tune may times thereafter, as Al DiMeola and Frank Gambale took over on guitar. In those and later shows, he always had an impish smile, as though playing was a constant delight, a little magical, and working with great musicians nothing less than an honor and a gift.

His astounding career was a gift to all of us.

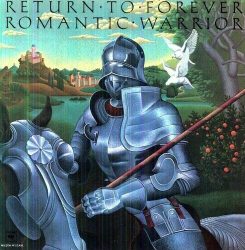

Paul Robicheau on Romantic Warrior (Columbia, 1976).

Paul Robicheau on Romantic Warrior (Columbia, 1976).

As a fan of the instrumental adventurism common to jazz fusion and prog-rock through the early ’70s, I was drawn to Chick Corea’s electric edition of Return to Forever — and ultimately to the quartet’s masterstroke, Romantic Warrior.

Experimentation and excess already marked the era. The Mahavishnu Orchestra (led by Corea’s Miles Davis peer John McLaughlin) and prog-rockers Yes had been flexing their muscles in long-form pieces with fiercely energetic solos on electric guitars and keys. Return to Forever, in contrast, debuted with graceful, Brazilian-flavored fusion. Yet Corea went for jazz-rock power as RTF evolved into a quartet. He secured that identity when guitarist Al DiMeola (hired out of Berklee at age 19) joined Corea, bassist Stanley Clarke, and drummer Lenny White for three mid-’70s albums.

Romantic Warrior streamlined the band’s sound with a clarity that had been missing in the chunky funk of RTF’s previous outing, 1975’s No Mystery. The studio sound was honed by major-label production at Colorado’s Caribou Ranch, where rockers Elton John and Chicago had recorded. The focus in this edition was on the showy, virtuosic aspects of fusion, with nimble, almost competitive solo rounds from every member but drummer White, who grounded this curlicue circus with brisk undercurrents punctuated by fat fills across his deep, springy toms.

The solo tradeoffs hit a peak on the album’s grandiose 11-minute closer “Duel of the Jester and the Tyrant.” DiMeola got the last word, with his spiraling speed runs lashing the music into even higher gear than Corea’s bubbling, pitch-bent Minimoog ride or Clarke’s piston-fingered bursts of guitar-like dexterity on electric bass.

Yet RTF flowed with passion and personality beyond the pyrotechnics. Those are qualities I didn’t hear enough in Corea’s late ’80s Elektric Band, even though the fusion of that group might have been more technically sophisticated.

Romantic Warrior truly soared thanks to Corea’s compositional flair for lyrical melodies that reflected his feel for Latin jazz and a sense of the baroque that fit the album’s medieval concept. He composed half of the album’s six tracks and displayed his skill on several keyboards, from stately and spritely synths (“Medieval Overture”) and his bright signature Fender Rhodes to moody ribbons of acoustic piano on the elegantly assembled title track, with DiMeola’s flamenco flurries serving as a perfect foil.

The group’s cohesion extended to the tunes contributed by his RTF bandmates, from White’s slinky funk launchpad “Sorceress,” to DiMeola’s gliding jazz-rock stomp “Majestic Dance,” to Clarke’s playful “The Magician,” salted with bells and whistles.

This RTF quartet disbanded after Romantic Warrior to pursue solo projects, and perhaps that made sense after such a definitive statement. I saw the group revisit the music on reunion tours in 1983, 2008, and in 2011 (with guitarist Frank Gambale in place of DiMeola and violinist Jean-Luc Ponty as guest). Yet those reunion dates didn’t quite match the magic of the studio album or a live performance on British TV the same year Romantic Warrior was released.

Cooperative Groups: The Three Quartets Band with Michael Brecker (1981) and Touchstone with Paco de Lucia (1982)

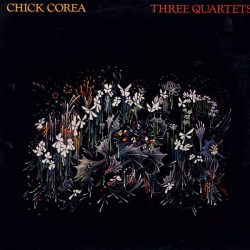

Allen Michie on Three Quartets (Warner Brothers, 1981).

Corea assembled what was arguably the best possible modern jazz trio in early 1981 and it became the foundation for Three Quartets, one of the best jazz albums of the 1980s.

Corea assembled what was arguably the best possible modern jazz trio in early 1981 and it became the foundation for Three Quartets, one of the best jazz albums of the 1980s.

Eddie Gomez, the bassist, was a contemporary of Corea’s at Julliard. One of his first gigs after graduation was a spot in the Bill Evans trio in 1966, becoming the anointed heir to Scott LaFaro as one of the best exploratory and supportive bassists a pianist could ever hope to have, and continuing with Evans until 1977. Gomez is recorded beautifully on Three Quartets, up in the mix so you can appreciate the extent of his contribution and the resonant sound of his instrument. His rubbery and harmonically advanced solos command rather than deflect attention.

Steve Gadd was the A-list session drummer throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, and he’s still in excellent form today. But after appearing on so many hit records, he wasn’t taken very seriously by the jazz cognoscenti. He’s a revelation on Three Quartets, swinging with both a jazzman’s instinctive flexibility and a studio pro’s attention to the smallest details of dynamics and solo support.

Michael Brecker on tenor sax makes it abundantly clear on Three Quartets that he was not just one-half of the Brecker Brothers. He stepped up to the mic and stepped into history here with a solo voice every bit as personal and self-assured as those of Coleman Hawkins, Sonny Rollins, or John Coltrane. Much was made of Brecker’s masterful debut album Michael Brecker (Impulse, 1987), but anyone who considers that to be his definitive early statement needs to hear his work on Three Quartets, recorded six years earlier. It’s all here, and it’s essential Brecker.

Finally, there’s Corea. He rumbles like McCoy Tyner, spins webs of melody like early Keith Jarrett, and runs the keyboard like Oscar Peterson. But from the first note he is unmistakably Chick Corea, pouring his personality and passions into these compositions (one dedicated to Duke Ellington, another to John Coltrane) and his playing.

Listen to Three Quartets as one of the peak performances from Gomez, then again as the renaissance of Steve Gadd, then again as the true debut album from Michael Brecker. Then listen to it a fourth time as one of Chick Corea’s masterpieces, as both a player and a band leader. With Three Quartets, Corea shows a Miles Davis–level instinct for finding greatness in others, giving them demanding and ambitious music, and turning them loose to find their own voices as they sail above it.

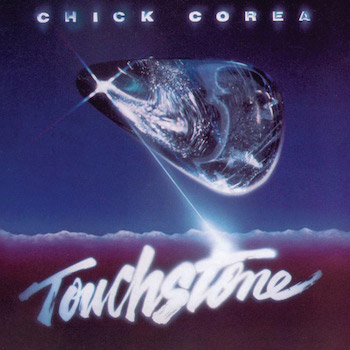

Jason M. Rubin on Touchstone (Warner Brothers, 1982)

I went to college (UMass Amherst) from 1981-1985. I went in a hardcore fan of progressive rock and came out a fledgling student of jazz. Chick Corea was my gateway from one to the other. Someone early in my college career played me the Return to Forever album Romantic Warrior and my first thought was that it sounded like Yes or Emerson, Lake & Palmer. With banks of electric keyboards and synthesizers, complex arrangements, and lightning fast solos, the essential distinction between prog and fusion seemed to be that fusion eschewed the fanciful lyrics and spacey passages of prog. Regardless, it was musicianship of the highest order, which is what had drawn me to prog in the first place. So I was hooked.

As luck would have it, 1982 became a musical harmonic convergence of sorts for me, because Miles Davis came to play and in advance of the show I decided to buy one of his albums. In a Silent Way caught my eye because it featured Chick on electric piano. The connections were coming together for me.

In addition, Corea released a new album that year: Touchstone, featuring flamenco guitar master Paco de Lucia, and they, too, were playing UMass. The disc turned out to be a good entry point for me because Corea gave listeners a bit of everything on it — a mix of electric and acoustic, lineups that changed with every track, and various styles of jazz. The title suite (which de Lucia once told fellow flamenco guitarist Ruben Diaz was his best work) was evocative of Chick’s longstanding love of Spanish music, most deeply pursued on 1976’s My Spanish Heart. Another de Lucia feature, “The Yellow Nimbus,” follows. Corea plays acoustic piano as well as electric keyboards and synths on both tracks.

In addition, Corea released a new album that year: Touchstone, featuring flamenco guitar master Paco de Lucia, and they, too, were playing UMass. The disc turned out to be a good entry point for me because Corea gave listeners a bit of everything on it — a mix of electric and acoustic, lineups that changed with every track, and various styles of jazz. The title suite (which de Lucia once told fellow flamenco guitarist Ruben Diaz was his best work) was evocative of Chick’s longstanding love of Spanish music, most deeply pursued on 1976’s My Spanish Heart. Another de Lucia feature, “The Yellow Nimbus,” follows. Corea plays acoustic piano as well as electric keyboards and synths on both tracks.

After that is a short but lovely tune called “Duende” with the great alto sax player Lee Konitz. Corea plays acoustic piano on the piece, which also features violin, cello, and bass. Flip the record over and you get the exact opposite: a truly electric reunion of Return to Forever with guns a-blazing on the nine-and-a-half-minute “Compadres.” That’s followed by “Estancia” with Corea on electric keyboards being supported by three percussionists. The album’s final tune, “Dance of Chance,” features horns playing complex unison lines with Corea’s electric keyboards and synths, not unlike Stevie’s Wonder’s “Superstition” and “Sir Duke.”

The concert was mesmerizing, and I saw him five more times after that, the last time in 2017. Touchstone remains a favorite though it’s an oft-overlooked entry in his extensive discography. But what it represents — his restless curiosity and creativity, his refusal to be bound to any given instrument or style, and his desire to work with only the very best players — is what made Chick Corea my favorite living musician. And though he’s no longer living, he really was one of my most important musical touchstones, and the ripples of his influence continue to flow.

Trios

Milo Miles on Trilogy at the Newport Jazz Festival, July 2016.

Milo wrote about 2016’s Saturday concert at Newport for the Fuse. That show included a set by Corea’s Trilogy trio, with Christian McBride on bass and Brian Blade on drums.

Steve Elman on the Vigilette Trio at Scullers, September 2018.

This spinoff of the cooperative group The Vigil was another in the series of outstanding Corea trios — this one devoted mostly to traditional jazz repertoire and his own straight-ahead tunes. I wrote about their week-long residency in Boston for the Fuse, and I’m happy to say that my observations there still hold. I well remember the warmth with which the hometown crowd embraced him, but now I also feel a tinge of melancholy, since it was my last chance to see him perform.

Duets

Michael Ullman on duets with Gary Burton and Herbie Hancock.

Michael reviewed these two memorable Symphony Hall duet concerts for the Fuse: Corea and Burton in 2012 (with guests the Harlem String Quartet and Gayle Moran) and Corea and Hancock in 2015.

Solos

Steve Feeney on Chick Corea Plays (Concord Jazz, 2020).

Steve reviewed this CD, Corea’s last release to date, for the Fuse.

Formal compositions

Steve Elman on Corea’s The Continents:

In 2012, I wrote about Corea’s biggest and most ambitious piece for orchestra for the Fuse as part of a series on piano concertos influenced by jazz.

Adventurous post-bop, 1966-69

Steve Elman on Tones for Joan’s Bones (Vortex, 1966).

We circle back to the beginning.

I listened with delight to Corea’s supremely confident debut LP as a leader when it was first issued, thinking, “This guy has really arrived.” I listen today with something like amazement at how fresh the music sounds. “Litha” remains one of Corea’s most engaging tunes. “Straight Up and Down” is a group performance that is mighty and delicate at the same time, with all five players at creative peaks. Throughout the date, the late trumpeter Woody Shaw and the late Joe Farrell, doubling tenor and flute, deliver solos that are among the best of their careers. Steve Swallow is heard here on acoustic bass, reminding us of just how good he was on that axe. And Corea’s choice of the explosive Joe Chambers, drum anchor for so many great Blue Note sessions (and still going strong in 2021!), was perfect.

I listened with delight to Corea’s supremely confident debut LP as a leader when it was first issued, thinking, “This guy has really arrived.” I listen today with something like amazement at how fresh the music sounds. “Litha” remains one of Corea’s most engaging tunes. “Straight Up and Down” is a group performance that is mighty and delicate at the same time, with all five players at creative peaks. Throughout the date, the late trumpeter Woody Shaw and the late Joe Farrell, doubling tenor and flute, deliver solos that are among the best of their careers. Steve Swallow is heard here on acoustic bass, reminding us of just how good he was on that axe. And Corea’s choice of the explosive Joe Chambers, drum anchor for so many great Blue Note sessions (and still going strong in 2021!), was perfect.

The follow-up sessions, which produced Is and Sundance (1969) brought Shaw back for more superb contributions. If the other front-line players on those releases, Bennie Maupin and Hubert Laws, don’t quite mesh with Corea the way Farrell did on the debut, neither of them disappoints.

But Tones for Joan’s Bones is not just great for its time. It holds the seeds of almost everything Corea would do. The tunes show that stream of melody that Corea could turn on as if it were a faucet. The acoustic band here is just as forceful as his electric groups were. The intuition in the ensemble work sets the stage for his stints with Miles Davis and Circle. The relationship with Joe Farrell endured; Corea joined three of Farrell’s LPs as a sideman, and he brought Farrell back to his own group in both of the vocal editions of his most popular ensemble, Return to Forever. The piano spots here look ahead to his long run of trio dates with Miroslav Vitous, a bassist who has a grace and freedom akin to that of Swallow. And The Touch is on ample display, that remarkable ability Corea had throughout his life (how did he manage this on electric keyboards?) to speak with lightness and power at the same time. The Touch is perhaps his most distinctive quality as a player.

We are not likely ever again to have such a rich and varied legacy of recorded music from such a versatile artist. Consider yourself lucky to have lived during Chick Corea Time.

A detailed Chick Corea discography, covering his earliest recordings to releases as recent as 2012, can be found here.

CD releases of his later years are listed by allmusic.com.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: Allen Michie, Chick Corea, David Daniel, Evelyn Rosenthal, Milo Miles, Paul Robicheau, Steve Elman, Steve Feeney, Steve Provizer, and Michael Ullman

Thanks for this wonderful overview of Chick’s long and adventurous career! I would just add that at the beginning of the article, when talking about Chick’s major influences, McCoy Tyner needs to be added to that list. An album like “Now He Sings, Now He Sobs” would not have been possible without it…and that holds true for many of the sessions he did during that period.