Streaming Docs: The Best of 2020 in Review — Part 1, Past and Present

By Neil Giordano

2020 offered another rich year for the documentary form, well beyond the tabloid entertainment of the likes of Tiger King

Writing a column about streaming documentaries would seem to be a plum assignment in 2020. We were all trapped inside, often staring at screens for hours at a time. So the world of cinema became one of our go-to solaces, even if it meant we had to watch in our living rooms. Yet, the strange new reality wasn’t necessarily all that good for the documentary industry. Over the past few years, streaming platforms have become the accepted new home for major documentary releases and that positioning has given them growing cultural prominence (even cachet). But, suddenly, everything was streaming. With movie theaters mostly closed and major releases down to a trickle, the buzz about movies in 2020 turned to the release cycles for indie film and, eventually, Hollywood blockbusters. Documentaries were shunted to second banana status once again, lost in the big budget shadows of Tenet and Wonder Woman 1984.

The streaming platforms adjusted their algorithms: feature films and original series dominated front pages, documentaries were pushed to the margins once again. Which documentary caught the culture’s attention in 2020? Tiger King, Netflix’s lurid series about exotic animals and even more exotic humans. The series might be the personification of this sad phenomena: if we can’t go to the movies, let’s fill the vacuum with addictive sensationalism.

In addition, documentary distributors in 2020 had to tinker with their already fragile business model. Films slated for theatrical release ended up with one-off streaming releases for a week or two, with Hulu and Netflix and Amazon eventually picking them up months later. They were buried in corporate-controlled algorithms. Meanwhile, without the infrastructure of film festivals to connect filmmakers to distributors and streaming vendors, 2021 may be an even stranger year ahead.

That said, 2020 offered another rich year for the documentary form, well beyond the tabloid entertainment of the likes of Tiger King. An array of styles and subjects eventually found their audiences. I’ve presented my picks in three parts this year. Part 1 highlights a few films that not only revisit the past, but also reexamine the ways we revisit the past. Are we looking for truth or schmaltz? Documentaries offer us all of the above.

A scene from Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets.

Equal parts barfly ethnography and gritty nostalgia, Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets has the feel of a narrative film…and that’s no accident. It is presented as the last night of a Las Vegas dive bar called the Roaring 20s that is closing for good. But the movie is, in fact, a cheat. The bar’s regulars and barkeeps are all played by nonprofessional actors assembled from other bars, and it was filmed on location in New Orleans (with a few exteriors shot in Vegas) in a marathon 18-hour shoot.

So, is this still a documentary? Maybe, maybe not. The directors, brothers Bill Ross and Turner Ross, are known to be genre-benders, inventing scenarios where their actor-subjects are invited to take up residence; in their film Tchoupitoulas (2012) three brothers roam the New Orleans cityscape at night. Here, the Rosses filmed on a closed set, with fly-on-the-wall cinematography and multiple microphones stashed about. They gathered their cast and told them the setup; they were then asked to create their personas based on the scenario. There’s the cantankerous know-it-all spouting nonstop nonsense, a Vietnam vet whose brooding is nurtured by his private demons, and the Wife of Bath archetype, a woman of a certain age who can cuss like a sailor and flash her barmates with glee.

Any plot? Conflicts rise and fade away, strong arguments are quelled with combatants stepping outside for a few moments of fresh air. Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets has the gabby feel of early Robert Altman, though overseen by the spirit of Eugene O’Neill (the directors credit The Iceman Cometh as an inspiration). Its finest moments show how the best documentaries draw on skillful editing to generate story arcs from wisps of character. Take Michael, the bar’s white-haired resident philosopher-king; he opens the film by shaving in the bar’s bathroom. He never leaves the place: he reads, takes his meals sitting on a barstool, and holds countless conversations with whoever sits next to him. He finishes the night falling asleep, his head down on the bar, next to a scattering of empty glasses.

There’s a “true” story in Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, but it is generated by the atmospheric joys and gloominess of the saloon’s denizens. The scenario is simulated, but the film reminds us of what it is like to hang out in places where “everybody knows your name,” even if the “everybody” is someone you just met that night and you may never see again. Arts Fuse review

The “Biospherians” pose for the camera during the final construction phase of the Biosphere 2 project in 1990. Left to right are: Mark Nelson, Linda Leigh, Taber MacCallum, Abigail Alling, Mark Van Thillo, Sally Silverstone, Roy Walfo.

From one enclosed space to another. Spaceship Earth also focuses on a group of sometimes fascinating people trapped inside a situation ridden with conflict. The setting this time is Biosphere 2, the early ’90s experiment in extra-planetary life, housed in a glass-walled facility outside Tucson. The film’s most impressive achievement is its healthy dose of revisionism; the oft-mocked project has been memorialized as a calamitous boondoggle concocted by hippie scientists. Instead, here we are offered a portrait of idealists taking advantage of intricate planning by an array of impressive individuals who saw the Biosphere as a heroic endeavor, admittedly one plagued by external politics, poor group dynamics, and power struggles between scientists and funders, the latter hell-bent on drumming up good publicity.

The film’s illuminating first act offers archival footage of the long history of accomplishments that culminated in the Biosphere. Led and partly funded by social entrepreneur John Allen, the initial project was the Synergia Ranch in New Mexico — home to a geodesic dome — a detail that would later similarly grace the Biosphere. The Ranch, populated by a number of the future “Biospherians,” attempted — and mostly succeeded — in fusing art, economics, and science. The effort drew on many of the futurist, mid-century ideals of notables such as Buckminster Fuller (whence the title of the film). By the mid-’70s the group set their sights on building their own oceangoing ship, the Heraclitus, which sailed around the world. (The vessel still cruises today, conducting oceanographic research.) Eventually, the “Biospherians” turned to for-profit enterprises worldwide in order to raise money. “We weren’t a commune; we were a corporation,” remembers one of the group. Their resourcefulness seemed boundless. Indeed, the sheer level of brainpower and creativity of these dreamers belies the myths about hippy-dippy incompetence that have overshadowed the Biosphere’s numerous wonders.

Yes, the movie flags a bit in its process-focused sections about the problems that plagued the Biosphere itself. But overall what emerges is an inspiring homage to the scientific method and its reliance on failure to pave the way for future success. Also on display is welcome proof that a very American spirit of optimism drove the Biosphere dream: a vision compounded of know-how and pragmatism dedicated to sustainable economics and environmentalism.

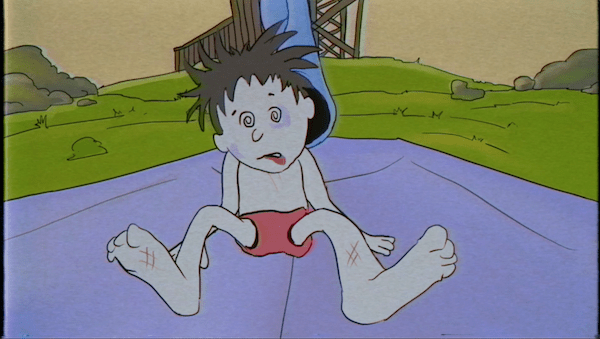

An animated still from Class Action Park.

Jumping back a few years, into the ’80s, Class Action Park is a lighthearted look at another cultural phenomenon. Ask any New York metro-area teenager of that era about their youthful peak experiences and you’ll hear stories of the most infamous amusement park in American history. For kids, Action Park, aka “Traction Park,” of Vernon Township, NJ, became the place to be. Why? There was its ubiquitous television advertising. And then there was the allure of stories about those who survived the “absolutely insane” rides.

The film takes considerable enjoyment in separating urban legend from fact. Though that’s ostensibly an easy task, because all of the “tall tales” turn out to be true: the towering loop-the-loop water slide that greeted you on the way in the gate, the alpine slide where you propelled at what felt like light speed, the tumultuous wave pool that rivaled Charybdis, the tank-battle ride in which one resourceful participant brought his own gasoline and lit the tennis-ball ammo on fire. Writer/funnyman John Hodgman provides a voice-over narration, adding an aura of poker-faced absurdity to the proceedings. The grainy videotaped archival footage is interspersed with kitschy tongue-in-cheek animations.

The film’s highlights are the revealing, entertaining, and head-shaking remembrances from former staff and regular park attendees. Now middle-aged, they gleefully remember their teenage selves and how they personified the entropic ethos of the place, equal parts daring and stupidity, fueled by a combination of alcohol and hormones. The story of the park’s founder, Wall Street pump-and-dump conman Gene Mulvihill, could be its own movie. Mulvihill wanted to provide an experience that reflected his laissez-faire philosophy, described here as “something between Ayn Rand and Lord of the Flies.” His irresponsibility has been well documented: rides designed on pure whim, rumors of a machine gun in his desk drawer; a Caymans-based fraudulent insurance company of his own fabrication (no legitimate insurer would touch the place), and the inevitable connection to Donald Trump (it was ’80s New York after all). Somehow, the park survived Mulvihill’s 110-count indictment for various crimes, innumerable injuries and lawsuits and, most sensationally, multiple fatalities, before its 1996 demise. The film’s late chapters take a suitably dark turn, giving time to the families of the deceased. But the movie’s footage of kids enjoying themselves with pure abandon invites reverie for an era of free-range childhood — before cell phones, helicopter parents, and over-scheduled teenagers. Arts Fuse review

Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, available for rental on Apple+, Amazon Prime, and elsewhere). Spaceship Earth can be found on Hulu. Class Action Park is exclusively on HBO Max.

Neil Giordano teaches film and creative writing in Newton. His work as an editor, writer, and photographer has appeared in Harper’s, Newsday, Literal Mind, and other publications. Giordano previously was on the original editorial staff of DoubleTake magazine and taught at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.

Tagged: Bloody Nose Empty Pockets, Class Action Park, Neil Giordano