Television Review: “Class Action Park” — The Most Dangerous Place on Earth

By Sarah Osman

Visitors (of all ages?) were invited to drink copious amounts of liquor and possibly get laid. This was as close to Pinnochio‘s Pleasure Island as they were ever going to get.

Class Action Park, HBO Max

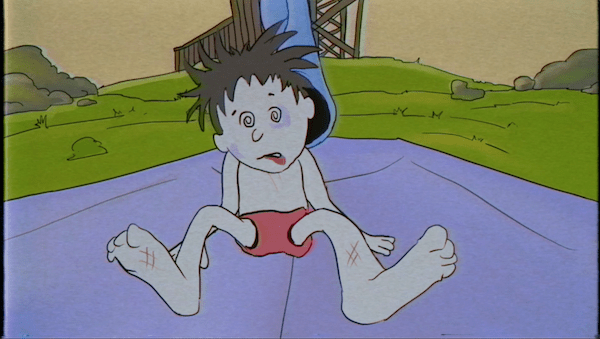

An animated still of an injured kid in Class Action Park.

The late ’70s and ’80s were a different time for American families. Today’s helicopter parents had yet to lift off. In this period, laissez-faire mothers and fathers often let their kids play in the streets well into nighttime. “Playdates” didn’t exist. You could argue that this relaxed attitude enabled the rise of the notorious theme park Action Park, which was built in the sleepy town of Vernon, New Jersey. Children and teenagers who grew up in neighboring New York City and other parts of New Jersey flocked to this supposed playground, which was anything but fun — if you were among those who were hurt, maimed, or even died on its various water slides and rides. Visitors (of all ages?) were invited to drink copious amounts of liquor and possibly get laid. This was as close to Pinnochio‘s Pleasure Island as they were ever going to get.

This is the location for the grisly non-fiction black comedy of HBO’s latest documentary, Class Action Park. Originally inspired by a 15 minute documentary, “The Most Insane Amusement Park Ever,” the film is an extended look at a place where basic common sense and societal rules did not apply. What we have here is a wild ‘80s movie come to bizarre life.

Action Park was created by the eccentric Gene Mulvihill, a former Wall Street big shot. After buying two ski resorts in Vernon, New Jersey, Mulvihill figured out that he could make money in the off-season months by opening up a water park. Though not just any run-of-the-mill amusement park, it was to be a water park where “you controlled the action!”

The focal point of Action Park was an enormous enclosed cannonball loop; the ride was constructed so it could only be completed by those of sufficient weight. Park security director Jim DeSaye recalls that Mulvihill offered park employees $100 to test what looked like — and turned out to be — a death trap. The first two kids came out with bloody mouths. The next children emerged with various cuts — they had scrapped against some loose teeth that had been embedded in the loop.

In the first half of the documentary, various performers reflect on their childhoods spent at Action Park. Comedian Chris Gethard reminisces about the Tarzan Swing, where guests swung from a giant rope 15 feet above freezing water. Falling off sometimes sent people into actual shock; guests who were watching would taunt the Swing’s victims to get out of the water. Former employees and even Mulvihill’s son also look back at the park mayhem. One employee recounts when a guest drove a motor boat on top of another motor boat — nearly decapitating one of the guests. Another employee recalls the park’s stab at first aid: a combination of alcohol and iodine that turned a toxic orange when it was sprayed on injured guests. Fist fights regularly broke out, and employees threw outrageous parties in the park at the end of every summer. Every single anecdote is completely and utterly insane. And, just when you figure that Action Park couldn’t be any more nuts, you find out you are wrong.

Mulvihill managed to keep the park going by buying “fake” insurance in the Cayman Islands. He often paid off injured or horrified guests so they wouldn’t sue. If they did, he would take them to court and always win. Each summer, Mulvihill added bigger, faster, and crazier rides that he promised that guests could control. He also later tossed in a German beer garden where he held various summer “fests.”

Much of Action Park’s absurdity is captured through grainy advertisements for the park, as well as a series of short animations that depict real life grotesque accidents. The cartoons are helpful because they turn the park’s bloody mishaps into pieces of wincing amusement. Thankfully, the simple, non-graphic visuals are not very violent – filmmakers Chris Charles Scott and Seth Porges were smart enough to understand that these atrocities should be suggested rather than recreated.

The second half of the documentary takes a much darker turn. Quite a few people died at Action Park, and it’s sobering to realize that not one – but two people – drowned in the deadly wave pool. Another man met a deadly fate when, after falling into the water during a kayak expedition, he was electrocuted because of faulty electric fans. George Larsson’s story is particularly tragic. The young man braved the lethal alpine slide. Due to the ride’s faulty brakes, he was thrown from the sled and hit his head on a few nearby rocks. It’s heart wrenching to listen to his mother and brother recount this terrible incident. It’s clear that they are both still in enormous pain over the senseless loss. It’s a stark reminder that, even though Action Park can come off like a warped but jocular version of Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, it was a very dangerous place. As fun as it is to laugh at the crass inanity of Mulvihill’s money making ideas, he is responsible for many injuries and deaths.

Class Action Park treats nostalgia with an intriguing mix of love and hate. While many think of Action Park fondly, others remember it (in their nightmares) as the fifth level of Dante’s Hell. The directors of Class Action Park are clever enough to show both sides of the story, but moral enough to never classify Mulvihill as a hero (as he is in the repellent 2008 feature film Action Point, which was inspired by The Most Insane Amusement Park Ever.) Let’s pray that Action Park was a product of its time — an unrepeatable experiment in water park horror.

Sarah Mina Osman is a writer living in Los Angeles. She has written for Young Hollywood and High Voltage Magazine. She will be featured in the upcoming anthology Fury: Women’s Lived Experiences under the Trump Era.

Tagged: Action Park, Class Action Park, Gene Mulvihill, HBO, Sarah Osman