Jazz Album Reviews: Ellis Marsalis and Monty Alexander — Lovers of Vinyl Rejoice

By Michael Ullman

This set proves Monty Alexander a more varied pianist than one might have thought. The Ellis Marsalis album is a final gift from one of America’s treasures.

Ellis Marsalis: For All We Know w/ Jason Marsalis, Newvelle Lp NVN-0004

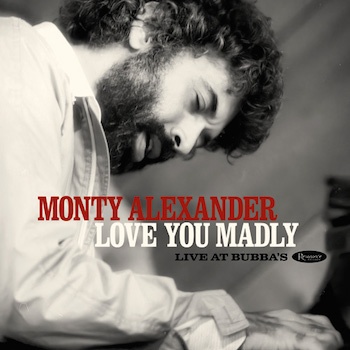

Monty Alexander, Love You Madly: Live at Bubba’s, Resonance 2lps

Lovers of vinyl rejoice: here are two high-quality, I would even say inimitable, jazz recordings produced by audiophile companies dedicated to recording and manufacturing the best possible LPs. They are certainly intriguing musically. “So there was really no modern jazz in New Orleans,” begins the late Ellis Marsalis in his notes to the exquisitely recorded Newvelle LP, recorded in February, 2020, less than two months before he died. Without elder statesmen to lead the way, Marsalis, pianist and patriarch of his extensive family of musicians, learned the new vocabulary on his own. He and a bunch of his peers bought 78 records of the new music. They frequented a record store they nicknamed the Bop Shop. He found the music “fairly simple”: “It was lots of blues, some ballads maybe, and what they called rhythm changes.” With friends like clarinetist Alvin Batiste and the great drummer Ed Blackwell, he listened to Bird and Diz, Max Roach, Miles, and Dexter Gordon.

Not too many people found bebop simple, but Ellis Marsalis was special. It’s fitting that in the notes reproduced here he talked about learning the music: his Newvelle LP has, as I see it, a theme of learning. For All We Know begins with a gently musing piece he calls “E’s Knowledge.” It’s serene, beginning with a spray of notes and continuing with a slow moving series of single notes that seem to fall into a theme. Marsalis implies that his knowledge has nothing to do with virtuosity or flash of any kind. It’s interior. When I read the title “Remembering John,” I wrongly thought of John Coltrane. The hero here is John Lewis and the piece is a reworking of Lewis’s “Django,” found, among other places, on the Modern Jazz Quartet’s Pyramid. There’s another tribute to that band: “A Groove for Bags” is a blues that refers to Milt Jackson’s “Bag’s Groove.” Both numbers feature Jason Marsalis on vibes. (He plays percussion elsewhere on the record.) The title cut, “For All We Know,” is another quiet, inventive, solo piece by Ellis Marsalis. I’m not sure if the conjunction of the two tunes, “My Funny Valentine/ Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” is meant to suggest the trouble that comes with romance. Marsalis begins “My Funny Valentine” patiently, with ravishing variations on the familiar theme. He can make a single accented note seem like an event. His wistful version of the ballad makes the transition to the lamenting spiritual seamless. He’s thoughtful rather than sentimental. Even playing a version of Milt Jackson’s famous blues “Bag’s Groove,” Jason Marsalis avoids imitating the now deceased vibist. It’s amusing that the Jason Marsalis composition found here is “Discipline Meets the Family.” The family couldn’t have responded better.

Born and raised in Jamaica, pianist Monty Alexander was a sideman on at least a half dozen Milt Jackson LPs. His family moved to Florida when he was in his mid-teens, but he performed what I heard him call “island music” at every opportunity. He’s a virtuosic pianist who can also play almost everything else. I like what the great pianist Kenny Barron says of him: “His playing has this kind of sparkle. It’s definitely music to make you feel good, and it’s geared towards that. It’s happy, happy and Snappy…. Joyful, that’s a better word. His music is always very joyful.”

On Love You Madly, the joy is spread out over two audiophile LPs. (It’s also available on CD.) Considering the vivid realism of the sound quality, I was surprised to read that the recording, which features bassist Paul Berner, drummer Duffy Jackson, and percussionist Robert Thomas, was made in 1982. It was recorded as a gift to Alexander by a professional engineer, Mack Emerman. The sound is remarkable: the piano is up front, and, at least on my audiophile system, seems like it’s in the room. Alexander sparkles, to use Kenny Barron’s term, on “Reggae Later.” He approaches the famous “Samba de Orfeu” indirectly, but when he gets to the melody, he plays exuberantly, with fast, precise single-note lines in the treble broken up by occasional locked-hand chords. The flow of ideas is remarkable. He plays “Fungii Mama,” once a hit for trumpeter Blue Mitchell, with a similar flow and good cheer. To show his range there’s a slow “Blues for Edith” and a dramatic “Body and Soul,” whose initial statement of the melody is broken up by grandiose glissandi, restless whole-tone scales and, in the bridge, thick dissonances. For all that, there’s a tenderness when the rhythm section finally joins in. This set proves Alexander a more varied pianist than one might have thought. The Ellis Marsalis LP is a final gift from one of America’s treasures.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.