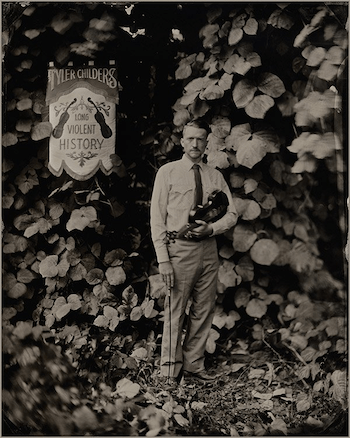

Folk Album Review: Tyler Childers’s “Long Violent History” – An Appalachian Murder Ballad for Breonna Taylor

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

The Kentuckian’s message is one of both heritage and empathy — and the necessity of both.

Tyler Childers has had a lot of success in recent years. Since the release of his second album, 2017’s Purgatory, the Kentuckian’s country music career has been on the rise. Nominated for a Grammy after the subsequent release of 2019’s Country Squire, Childers has been noted for undercutting Appalachian stereotypes. His self-described “working man’s country” embraces the blue-collar sensibility of Merle Haggard and Waylon Jennings, but he eludes the “bro-country” and “Americana” labels. His highly successful second and third albums (guided by their producer Sturgill Simpson) evoke a lively ’70s Nashville scene. They are filled with clever musings, conversational bons mots in real-world environments — while at the same time they embrace the high production qualities that make the songs viable commercial contenders.

Tyler Childers has had a lot of success in recent years. Since the release of his second album, 2017’s Purgatory, the Kentuckian’s country music career has been on the rise. Nominated for a Grammy after the subsequent release of 2019’s Country Squire, Childers has been noted for undercutting Appalachian stereotypes. His self-described “working man’s country” embraces the blue-collar sensibility of Merle Haggard and Waylon Jennings, but he eludes the “bro-country” and “Americana” labels. His highly successful second and third albums (guided by their producer Sturgill Simpson) evoke a lively ’70s Nashville scene. They are filled with clever musings, conversational bons mots in real-world environments — while at the same time they embrace the high production qualities that make the songs viable commercial contenders.

When receiving his award for Emerging Artist of the Year at 2018’s Americana Music Awards, Childers declared: “As a man who identifies as a country music singer, I feel ‘Americana’ ain’t no part of nothin’.” For him, the genre is a corrupting distraction, a profitable escape for country music singers from the demanding realities of the past and present. The corrosive corporate divide between “race records” and “country records,” set up a century ago, severed American music into racial consumer groups. Childers rejects the false division between commercial viability and hallowed tradition. But he is also critical of the too easy distinction made between tradition and calls for social responsibility.

Childers’s Long Violent History spends a lot of its time in the traditional, before it reaches its culmination, a powerful title track that supports Black Lives Matter. It is a sort of Appalachian murder ballad for George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. The finale crowns an otherwise instrumental old-time fiddle album that is far from a “rejection of traditional values.” Yet Childers continues his mission to undercut caricatures of rural whites. In the video statement released to accompany the album, Childers implores his “white rural listeners” to “start looking for ways to preserve our heritage outside of lazily defending a flag with a history steeped in racism and treason.” One of the ways he suggests they pay homage is by “learning a fiddle tune.” In other words, precisely what Childers himself is doing in Long Violent History. He’d originally “planned to package it as an old-time fiddle album and let the [last] piece make its statement on its own, taking the listener by surprise at the end.” With notes written by North Carolina old-time songster Dom Flemons, Long Violent History sidesteps music biz and music journalism bullshit in order to examine the assumptions made by the community of historical-authenticity geeks whose work has inspired the traditionalism of such commercial artists as Childers.

Perhaps the most recognizable track here for old-time aficionados is “Bonaparte’s Retreat,” part of a family of British and American tunes that commemorate Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia. It was an occasion which called for much merriment among the Scots-Irish who filled the ranks of the British military. The same defeat, remembered in Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, has remained a festive tune to American ears: many think it is a celebration of the War of 1812. Childers’s version of the song (which has a varied and distinguished history) is a testament to the rough-and-tumble imperial cannon fodder of the British Empire and their delight in seeing a presumptuous upstart taken down a peg or two. These sentiments were not only echoed in Appalachia, but throughout American populism more widely. “I hope that I’m doing my people justice,” Childers has said, “and I hope that maybe someone from somewhere else can get a glimpse of the life of a Kentucky boy.”

This fidelity to his people explains why Childers chooses songs inspired by the Civil War. In the breakdown “Camp Chase,” West Virginia fiddlers told the tale of Solomon “Devil Sol” Carpenter, who used the song to fiddle his way to freedom from a Union POW prison in Camp Chase, OH (outside Columbus). Devil Sol performed the tune with so many fantastic flourishes — including, it is said, its two high notes — that he was released. If that story sounds familiar, it should. It’s “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” Orpheus escaping Hades because of his virtuosity on the lyre. In Childers’s persuasive treatment, it is possible to imagine the sounds of bones or buck dancing. The harmonica-filled air “Zolly’s Retreat” remembers the fall of Felix Zollicoffer in 1862’s Battle of Mill Springs. A very nearsighted Confederate general was duped by poor weather and rode right into Union troops, mistaking them for his own. A Union colonel killed him with a point-blank pistol shot in view of his then demoralized men. Serving as a counterpoint, perhaps, to “Camp Chase,” “Zolly’s Retreat” laments that human limitations can lead to tragic failure. Both songs compel listeners to look at “Confederate” history through a more complex lens than one-sided heroism. The modern resonance of these stories offer us “ways to preserve our heritage” that free us from our prisons of chauvinism or hubris … if only we learn how to properly identify friend and foe.

Bill Monroe’s “Jenny Lynn” keeps us in Childers’s home state of Kentucky, as does is “Sludge River Stomp.” Decidedly more somber than most “river stomps,” the tune can’t help but make one think about the most significant meaning of “sludge” in Appalachia today: coal slurry. (Sludge is the title of a Robert Salyer’s excellent 2005 documentary about Kentucky’s Martin County Sludge Spill.) “Squirrel Hunters” is a fife march with Allegheny roots popularized by West Virginia fiddlers (no relation to the 1863 tune that celebrated the Ohio militia’s defense of Cincinnati). “Midnight on the Water” is a Texan waltz written by Luke Thomasson, father of fiddler Benny Thomasson. On first listening, the most incongruent entry on the album is “Send in the Clowns,” composed by Stephen Sondheim for his 1973 musical A Little Night Music. Barbara Streisand, Judy Collins, or Frank Sinatra come to mind. But Childers knows that the popularization of such tunes, via the traditional medium of fiddle playing, is a part of folk culture. There has always been a direct connection between Broadway and the hollers; for example, the transformation of minstrel songs into folk standards. (The process is echoed in the tune “Long Violent History,” with its use of a motif from Stephen Foster’s “Old Kentucky Home.”) Also, note “Sludge River Stomp”’s nod to the “stomp” genre of Black Americans Fletcher Henderson, Rex Stewart, Coleman Hawkins, and Count Basie.

The final track clarifies the journey that the album takes us on. Opener “Send in the Clowns” is filled with sad skepticism about our dreams, but by the end Childers’s lyrics implore us to grasp at what is genuine in this moment … by focusing on its historical resonance: “It’s the worst that it’s been since the last time it happened / It’s happening again right in front of our eyes / There’s updated footage, wild speculation / Tall tales and hearsay and absolute lies.” These are falsehoods, but familiar ones. The same old clowns are in control, and the irony is that Childers’s “white rural listeners” have been victims in this circus: “It’s called me belligеrent, it’s took me for ignorant” and yet, “it ain’t never once made me scared just to be.” Can we empathize with that? Childers goes on to ask,“How many boys could they haul off this mountain / Shoot full of holes, cuffed and layin’ in the streets / ‘Til we come into town in a stark ravin’ anger / Looking for answers and armed to the teeth?”

Childers knows the limitations of his art, that he runs “the risk of mistakenly analogizing two groups of people.” But it is a risk worth taking, powered by artistic license, because it underlines that the lives of others matter as much as ours. In his introductory video, Childers asks some simple questions: “What if we were to constantly open up our daily paper and see a headline like ‘East Kentucky Man Shot Seven Times on a Fishing Trip?’ What form of upheaval would that create? I’d venture to say if we were met with this type of daily attack on our own people, we would take action in a way that hasn’t been seen since the Battle of Blair Mountain in West Virginia. And if we wouldn’t stand for it, why would we expect another group of Americans to stand for it? Why would we stand silent while it happened?” Childers wants to make Americans aware of their own history… the bloody entanglements of their traditions… and he will not remain silent. To take the right action in the present, we need to take a good long look at our long violent histories. Why? Because remembering those old visions… those old dreams… are the keys to a brighter future.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, Florida. He has an MA in History of Ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.

Tagged: Black Lives Matter, Breonna Taylor, Long Violent History

Exceptional! An abundance of wit!